ONE evening in 1859, Henry Pease arrived breathless and late for dinner back at his brother Joseph’s beachside house at Marske-by-the-Sea.

Henry had been out roaming the sands which, level and yellow, stretched several miles down the Cleveland coast to the old fishing and smuggling hamlet of Saltburn.

Apologising for his lateness, he explained that at Saltburn, where a beck caused a break in the towering cliff, he had spotted the future.

"Seated on the hillside he had seen, in a sort of prophetic vision, on the edge of the cliff before him, a town arise and the quiet unfrequented glen turned into a lovely garden,” his wife, Mary, later wrote.

Henry’s vision showed a seaside resort flourishing on the bleak, empty clifftop high above the waves. It would be connected by his railway into the growing metropolis of Middlesbrough, from where trainloads of daytrippers and holidaymakers could come to stroll on the beach and even dip in the sea – if they were fit enough to manage the climb back up to the town.

Cliff House in Marske-by-the-Sea, looking towards Huntcliff and Saltburn. Henry Pease was staying with his brother, Joseph, when he had the idea to create a railway resort at Saltburn

Quickly, Henry formed the Saltburn Improvement Company to develop the resort, and he co-designed its landmark, the Zetland Hotel, into which his railway ran so no tourist would have the kerfuffle of transferring luggage from the station to the hotel.

Other railway entrepreneurs also saw the potential: Darlington engineer John Anderson opened the Alexandra Hotel on the most prominent corner of the cliff in 1867.

Then they started work on attractions for the tourists: the gardens, the spa and then the pier, which was opened in May 1869.

But the pier needed a prom, which needed to be made of something sturdy to withstand the sea.

“This raises an interesting point,” says Peter Sotheran from up the coast in Redcar. “How to get them from the town centre station down to the beach?

“Saltburn Bank was too steep for horse-drawn carts, motor vehicles were still several decades in the future, and the more gradual slope down Hazelgrove, at the west end of Saltburn sea front, would lead them to a challenging pull across soft sand on the beach to the pier.”

The prom at Saltburn, by Rodney Wildsmith, showing the stone sleepers, complete with holes for the chairs, in the seawall

Perhaps this explains why in 1868, Mr Anderson – the principal promoter of the pier – instructed a Mr Henderson of Middlesbrough to sink a shaft for a cliff lift: it wasn’t for the tourists but so the heavy sleepers could be dropped to the beach.

However, the shaft ran into impenetrable rock and Mr Anderson abandoned the idea, leading to him being sued by Mr Henderson.

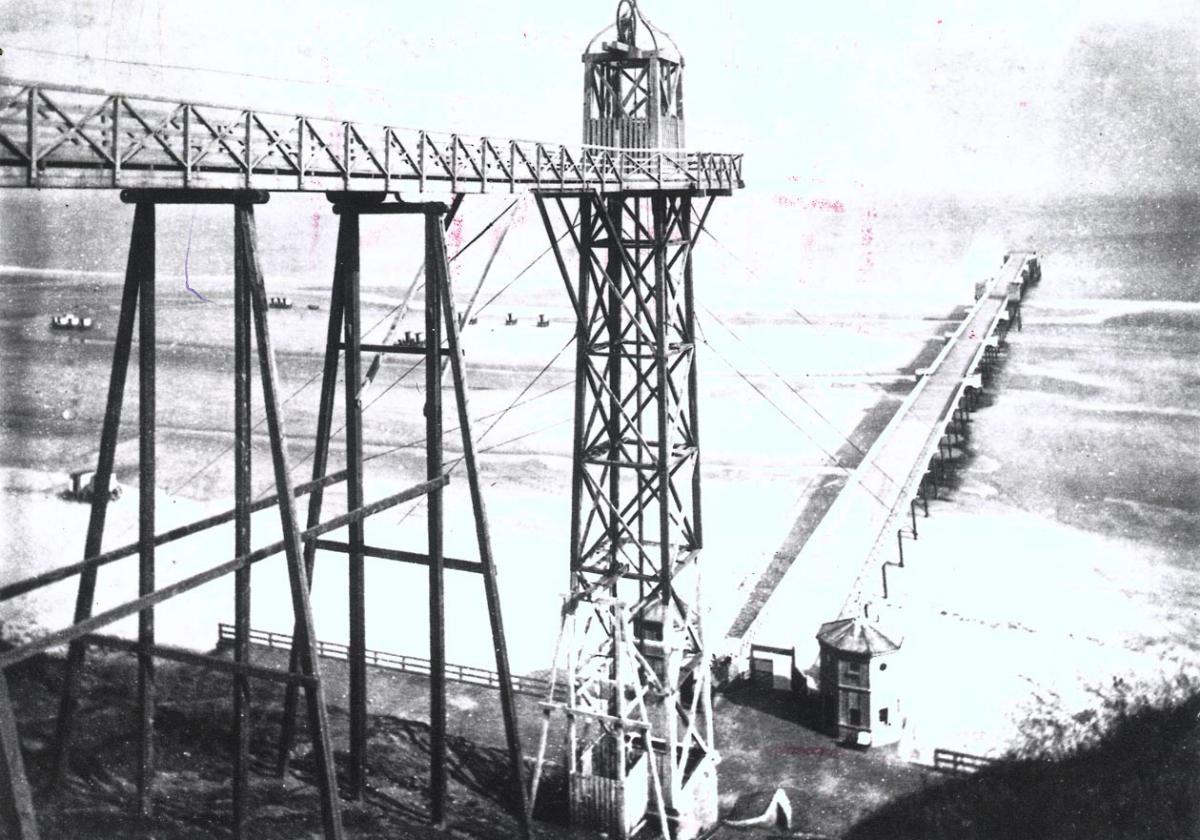

Then Mr Anderson adopted a new concept: an incredibly wobbly-looking vertical hoist.

People on the clifftop walked out along a wooden gantry supported by slender, spidery legs until, 120ft in the air, they climbed into a circular cage, which could hold 20 people. Using waterpower, it plummeted them down to the prom.

“It is often surmised that the vertical hoist was installed to carry visitors down to the beach and back up again,” says Peter.

“But look at this photograph of 1880. It shows a civil engineering site, not a tourist feature! The structure is rather utilitarian in appearance and lacks the refinement of Victorian tourism facilities. The lower promenade is still under construction, hence it is unlikely to be a major tourism attraction. And there is a crane conveniently placed at the hoist's foot to swing the sleeper blocks away.

Peter Sotheran's picture of Saltburn from 1880 showing the vertical hoist that was built to drop the stone railway sleepers to the promenade. Holidaymakers were also able to use it, although it had the worrying habit of getting jammed halfway

“This all gives credence to the argument that the vertical hoist was a piece of essential engineering to assist with building the lower promenade, rather than a later feature added for the benefit of visitors.”

So Saltburn’s first cliff lift was built not to stop the tourists from having to huff and puff their way back up the bank but so that the heavy sleepers, which the railway had donated for free, could be dropped down to the seawall.

The hoist opened in July 1870, but so much huffing and puffing did it prevent that some tourists were happy to use it – even though it developed the worrying habit of getting stuck halfway. The brave passengers paid 1d up from the beach and 1½d to go down.

Because it wasn’t built as a permanent tourist attraction, the wooden hoist, which was tethered to the side of the cliff by guyropes, soon began to rot. It was removed in 1884 and replaced by the country’s third water-balanced inclined tramway, which opened on June 28, 1884, and still runs.

- If you have anything to add to any of the items in today’s column, please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here