SALTBURN seafront is fabulous place for a holiday stroll, and if you go, keep an eye open for the stone blocks with circular holes in them that make up the sea wall.

Could the blocks, asks Rodney Wildsmith in Great Ayton, be connected to the stone sleepers laid on the Stockton & Darlington Railway 200 years ago that were mentioned in our article on the new booklet about the line which has been produced by the Friends group (D&S Times, Dec 10).

Construction of the line was beginning in 1822, and engineer George Stephenson decided that the rails should be 4ft 8ins apart. No one is quite sure why: there is a suggestion that there are cart tracks at Hadrian’s Wall of this size which is probably ideally suited for the physique of the horses which were then the motive force. This gauge was widely used in the North East collieries in which Stephenson learned his engineering skills, so he employed it when he built the line.

The rails were to be laid on blocks rather than on transverse sleepers. This left the centre of the tracks clear so that horses could still pull wagons on the line without tripping over the sleepers.

On the east side of the line, from Witton Park, the rails were to be laid on stone blocks quarried beside the line at Brusselton Hill, above Shildon.

Stephenson said that these blocks were to be "18 to 24 inches long by 14 to 18 inches broad, and ten to 12 inches deep, the top and bottom of each block to be parallel with each other".

These dimensions were chosen because they were big enough to support the rail and because they meant that each block would weigh about 75lbs. A single strong man of the day would, therefore, be able to lift the block without requiring a mate to help him, so cutting labour costs.

Sadly, a puny early 21st Century journalist struggles even to move what an early 19th Century navvy could lift.

The rails were attached to the blocks by cast iron fixings known as "chairs" – presumably because the rails sat on them.

An original stone sleeper, installed in 1822, showing the recess for the chair to sit in and the two bolt holes

The chairs were fixed to the blocks by nails. The quarry had to chisel the shape of the chair out of the stone to a depth of half-an-inch, and then drill two three-quarter inch deep holes for the nails.

Young boys were paid 8d a day for drilling 48 holes.

The quarry was required to have "8,000 of these blocks ready for use, and laid out ready for the loading of carts, by March 1, 1822, and that 8,000 should be ready every two months afterwards until 64,000 blocks should be ready for use".

Each stone block cost 6d to produce, but when transport costs were factored in, it was decided that they would be too expensive to take to lay to the east of Darlington.

So wooden blocks, which had to be "2ft 6ins in length, 6ins in breadth and six to eight inches in depth", were sourced from a firm of ship-breakers in Portsea, Hampshire. These old ships’ timbers cost 6d each, including delivery, and the first consignment of them – 9,200 of them, although many more thousands were required – arrived in Stockton in May 1822.

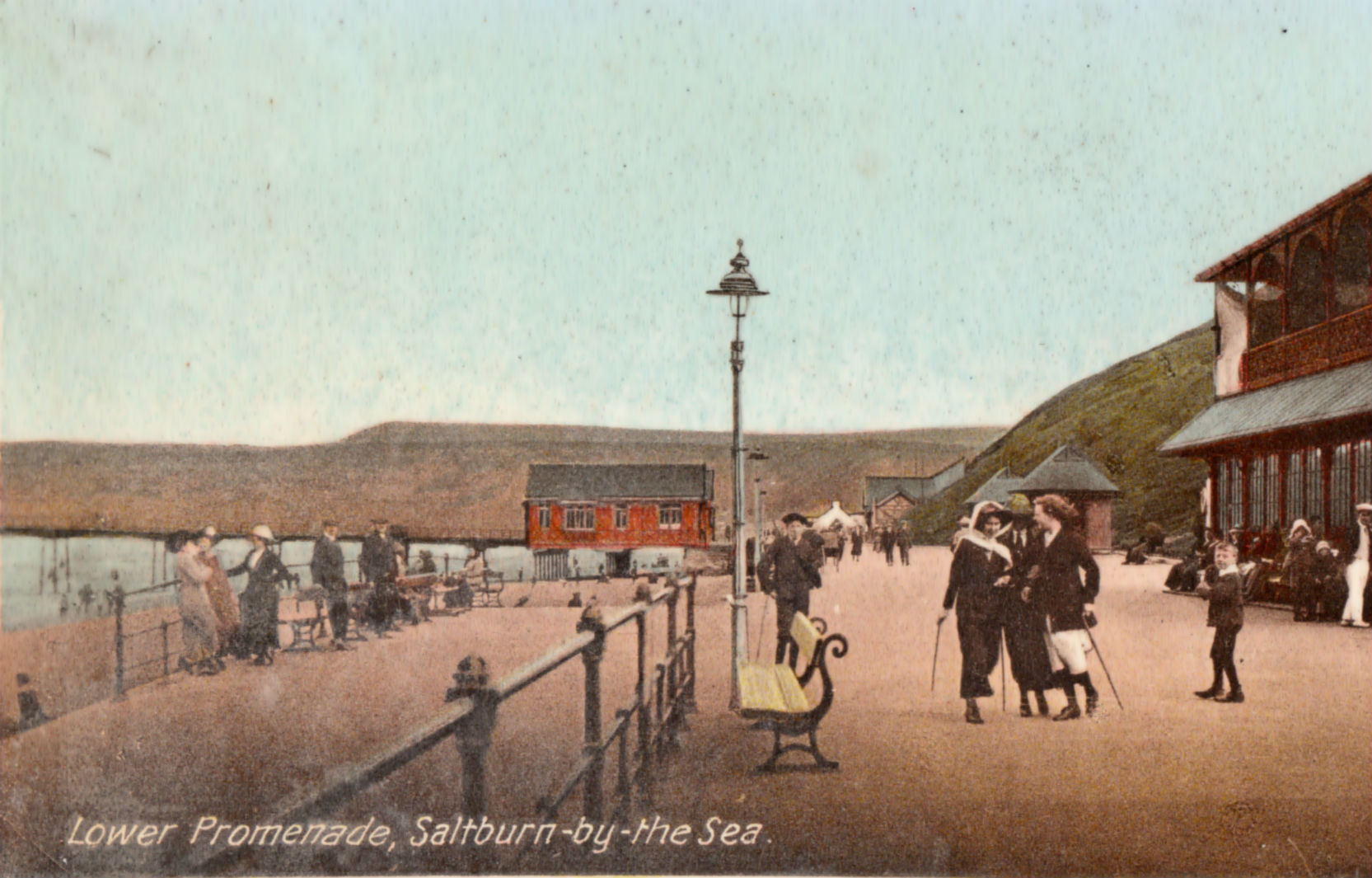

An Edwardian postcard showing the prom near Saltburn pier

All of the sleepers were in place for the opening on September 27, 1825, of the line, which was largely single track with passing loops.

The rules stated that horsepower should give way to steam power on the track, but when a horse-drawn coach heading west met another horse-drawn coach heading east, there was a free-for-all.

Most of these coaches had picked up their passengers from wayside pubs where the drivers may also have had one for the road as well. So there were drunken battles in the middle of the tracks as one group of passengers tried to either push their rivals’ carriage back to a siding or lift it off the tracks.

"Gentlemen," said engineer Timothy Hackworth at a meeting of railway directors in 1826, "I only wish you to know that it would make you cry to see how they knock each other's brains out."

By 1831, the railway was making enough money to lay two tracks along its whole length. All the 1825 sleepers were replaced by new, bigger stone blocks which were 2ft square and weighed two hundredweight (not even a navvy could lift one of those) to support the heavier trains which were already using the line.

New, bigger chairs were attached to the blocks by four bolts, and the old sleepers were rolled away, dumped, broken up or recycled.

In the seawall by the pier at Stockton there are stone blocks with two holes, four holes and even six holes in them.

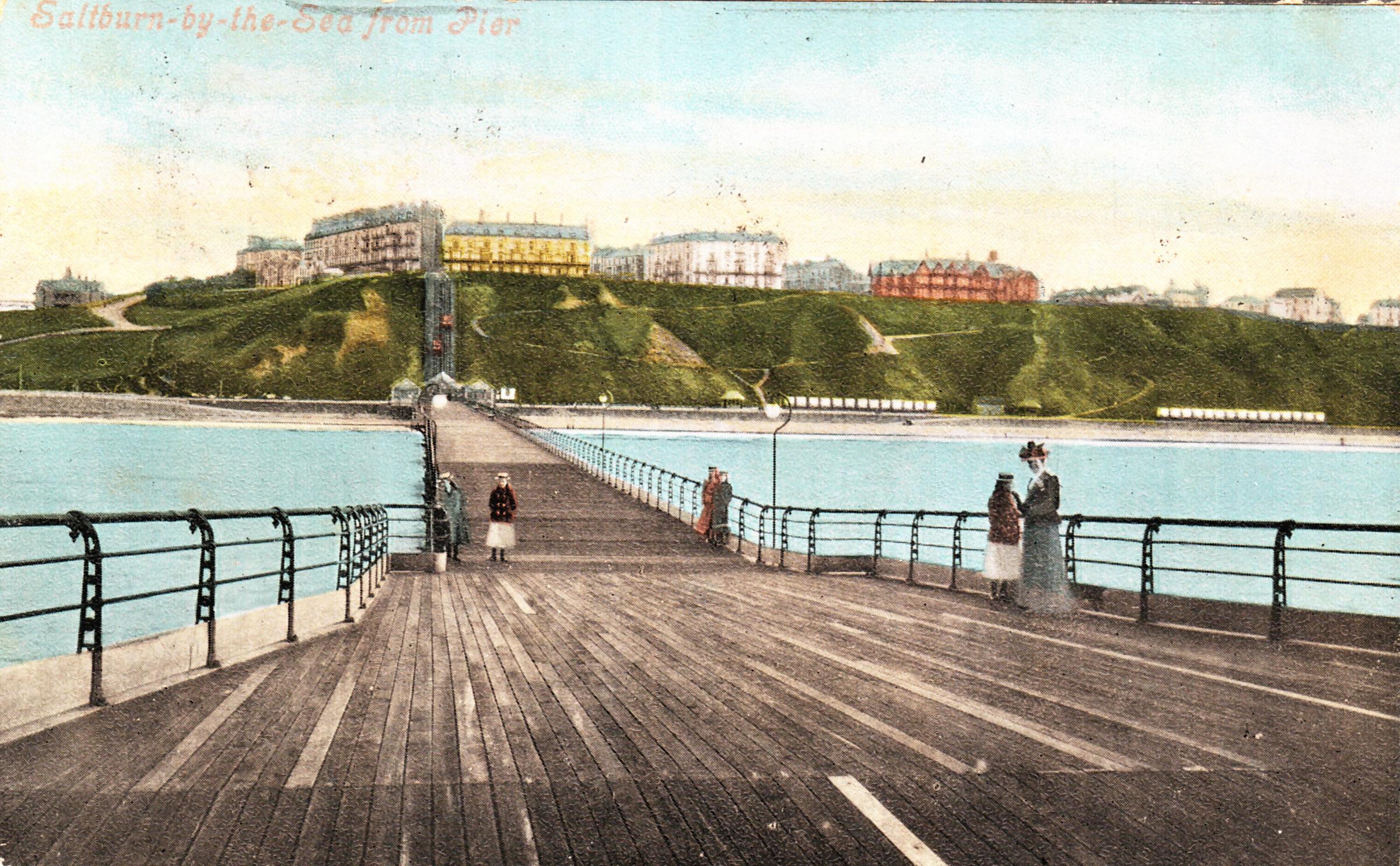

Saltburn, of course, was conceived as a railway resort, with trains running in to the cliff top Zetland Hotel so holiday-making passengers didn’t need to bother with lugging their luggage around the station.

The first section of promenade was built around the same time as the pier – the first of the pier’s legs was sunk on January 12, 1868, and it was opened in May 1869.

In his recently republished book, The History of Saltburn, Chris Scott Wilson says there are two theories about where the seawall blocks came from. One says Paddy Waddell’s Railway, on the North York Moors, while a report in the Saltburn & Cleveland Advertiser in 1927 says they came from the original trackbed of the Stockton & Darlington Railway.

“Whichever is correct,” concludes Chris, “inspection today reveals sets of drilled holes where bolts have held rail-chair seatings.”

So they definitely are old railway sleepers and it would seem most likely, given Saltburn’s close connection to the S&DR, that they are leftovers from the railway’s earliest days – perhaps even from the very beginnings of the two-holed sleeper. Have a look next time you are on the prom.

An Edwardian postcard view from Saltburn pierhead to the town..

THE scars of Paddy Waddell’s Railway can still be seen running ten and a half miles across the moors from Skelton, near Saltburn, to Glaisdale. Among the line’s promoters was Joseph Dodds, the Liberal MP for Stockton for 20 years. He hailed from Winston, in Teesdale, and became a solicitor. He was mayor of Stockton in 1857, and had finger in every iron, coal, shipping and railway pie in the Tees Valley.

When a direct train from Middlesbrough and Stockton to London was launched, it was nicknamed “the Dodds Express” because he was responsible for its introduction.

Highly regarded, he fell spectacularly from grace in 1888 when he was convicted of embezzling £13,800 (about £1.8m in today’s values) from a little old lady client.

In 1873, at Moorsholm, he cut the first sod for the railway which was intended to take iron ore from the east coast mines to the Glaisdale ironworks.

The contractor was John Waddell, of Edinburgh, who built several lines running into Whitby. He employed Irish labourers, and his foreman was an Irishman called Gallaher, and so the line – which was properly called the Cleveland Mineral Extension Railway – was nicknamed Paddy Waddell’s Railway.

The labourers dug cuttings, raised embankments, built bridges and gobbled up money. But the Cleveland iron industry was floundering – the Glaisdale ironworks closed in 1876 – and so it was never completed.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel