A couple of seasons ago, Leeds United fans became so enamoured with the play of Kalvin Phillips that they christened him the “Yorkshire Pirlo” after the Italian midfield maestro Andrea Pirlo, whose close control skills plus his vision, creativity and artistry helped him win both the World Cup and the Champions League.

But long before the “Yorkshire Pirlo” there was the “Yorkshire Piranesi”, George Cuitt, an engraver from Richmond whose vision, creativity and artistry, plus his close control of his engraver’s needle, allowed him to produce architectural prints of romantic ruins that are every bit as good – if not better – than the works of the Italian maestro Giovanni Piranesi whose etchings of the great buildings of Rome created an artform.

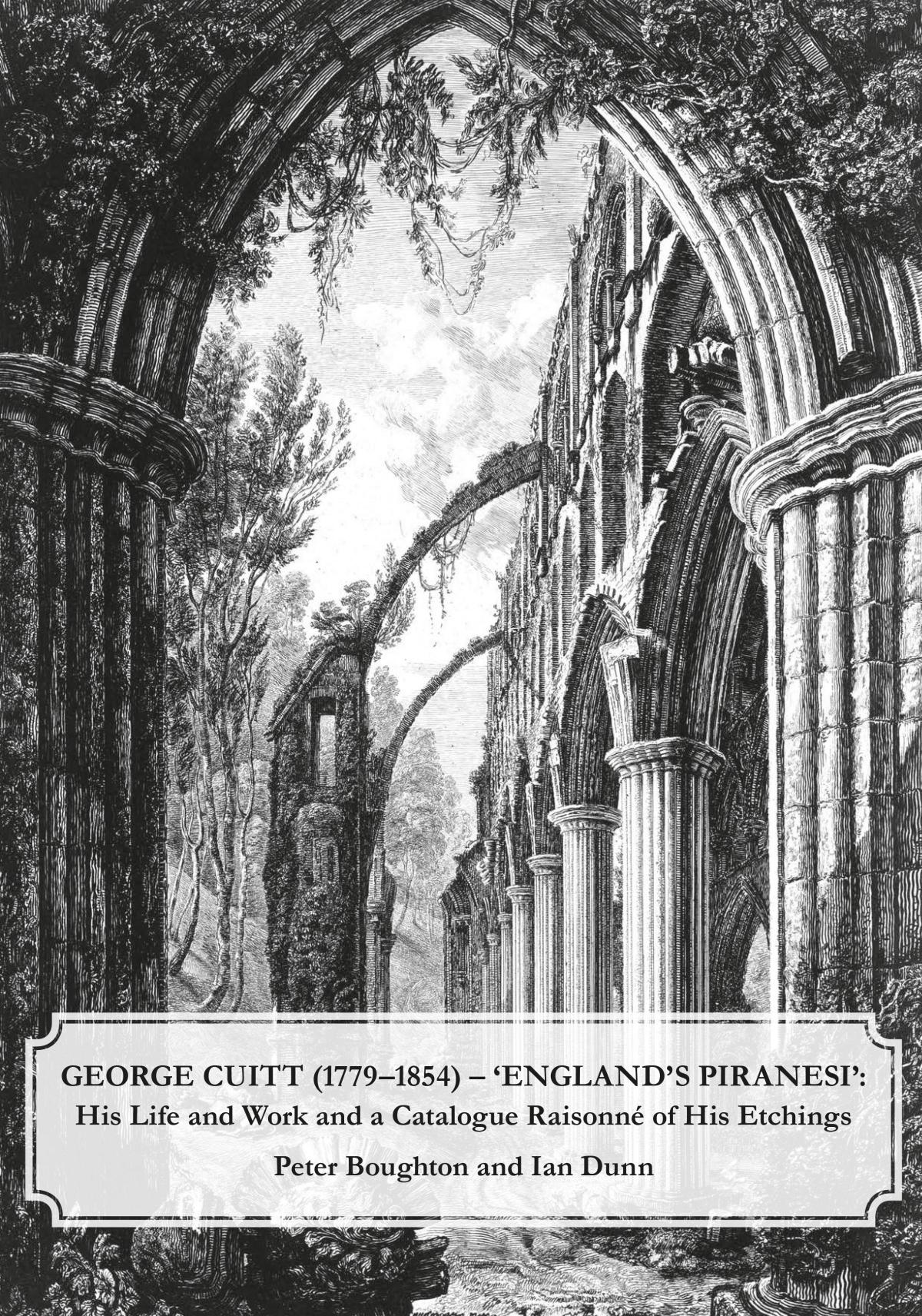

Now, after more than 20 years of painstaking work, all of the Yorkshire Piranesi’s works have been catalogued and reproduced in a fabulous hardback 400-page tome by the University of Chester.

And just as the Leeds midfielder has now moved up the footballing pyramid to Manchester City, so the Richmond engraver has been promoted. The book is called “George Cuitt: England’s Piranesi”.

Kalvin Phillips, the Yorkshire Pirlo, should not be confused with the Yorkshire Piranesi

It tells how Cuitt’s father, George Cuit, from Moulton, showed such promise as an artist while attending Richmond Grammar School that in 1769 Sir Lawrence Dundas, of Aske Hall, generously agreed to send him and a friend on a grand tour to Rome to soak up artistic inspiration.

He arrived just as Piranesi was at the height of his powers, producing detailed prints of Rome’s ancient buildings as well as creating great public curiosity about his engravings of “imaginary prisons” which deceive the eye with their geometrically impossible shapes.

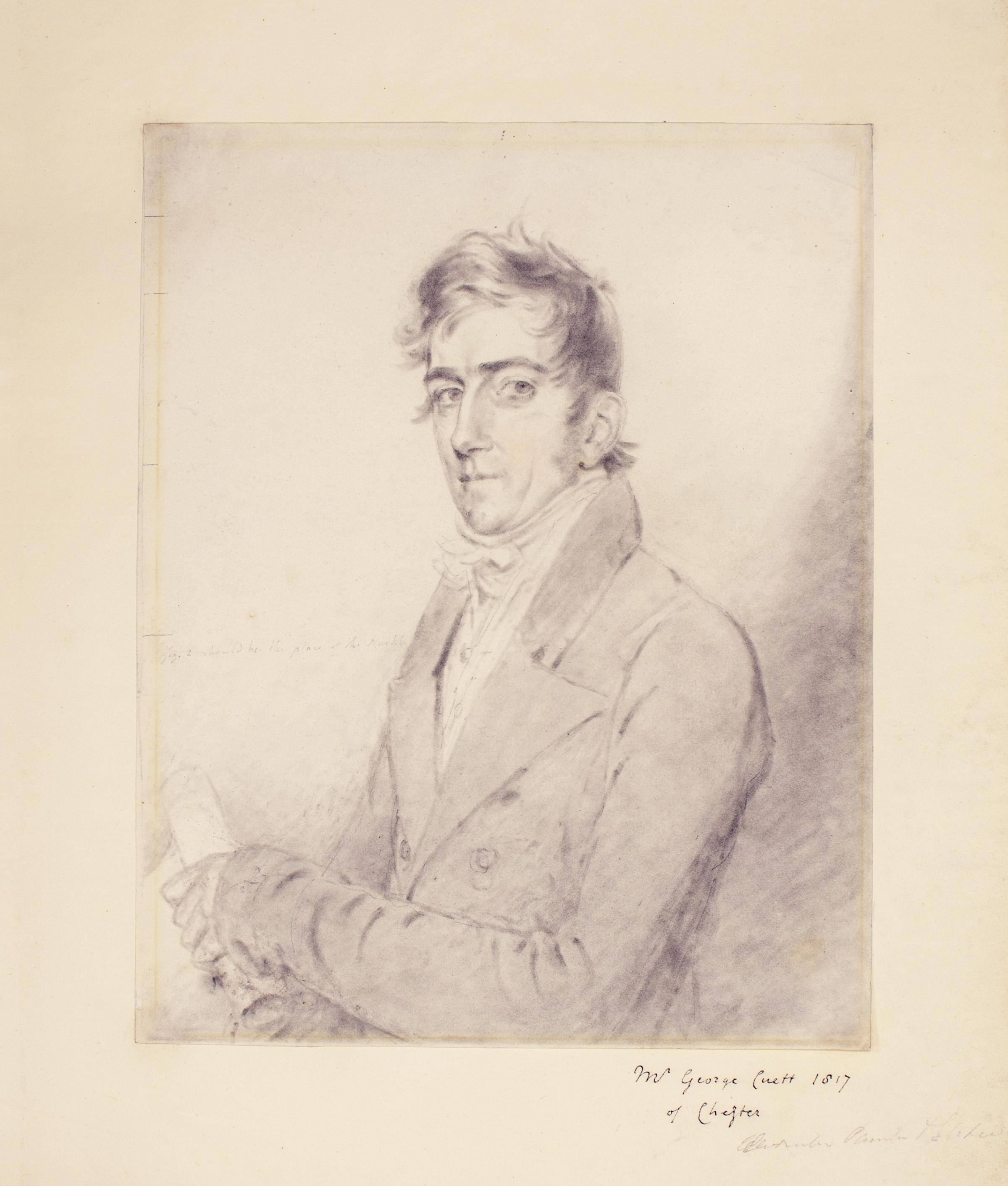

The engraver George Cuitt, by John Downman, 1817. (Grosvenor Museum, Chester)

After six years of study, George returned to Richmond with a “fine collection” of Piranesi’s etchings and enough skill to set himself up comfortably as an artist and teacher with patrons among the aristocracy and gentry of North Yorkshire.

In 1777, he married Jane Waine, of North Cowton, in South Cowton church, and their only surviving child, George, was born in Richmond in 1779. The boy briefly attended the grammar school, before completing his studies under his father – no doubt regularly consulting that collection of Piranesi prints.

To ensure his increasingly competent works were not confused with those of his father, around 1790, he began signing his surname with a double t at the end.

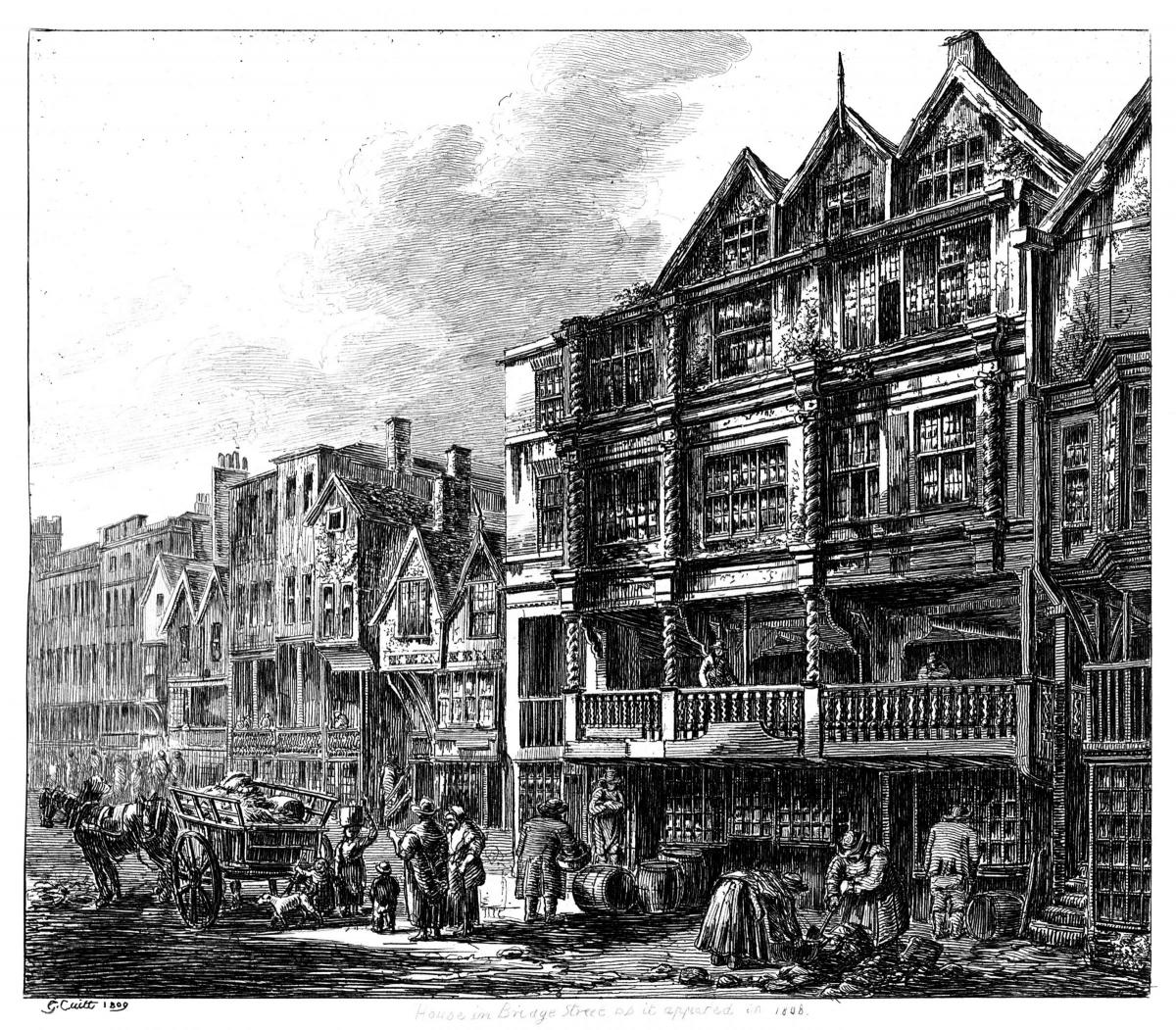

At the age of 25 in 1804, Cuitt moved to Chester to take up a post as a drawing master. Drawing in those days, as the books of Jane Austen reveal, was a hugely fashionable pastime among the wealthy, particularly among females, and George quickly gained a lot of lucrative lessons.

Rievaulx Abbey, Yorkshire, 1824. Cuitt is renowned for his wonderful ivy and trees, as this etching shows. The tree on the right also conveniently parted for him to reveal one of the abbey's pinnacles (Bree 2.58, Cheshire Archives and Local Studies)

In 1808, he married Catherine Ayrton, the daughter of the Ripon cathedral organist, and they lived in one of Chester’s famous double-decker streets at “row level” – which means they were above the shopfronts.

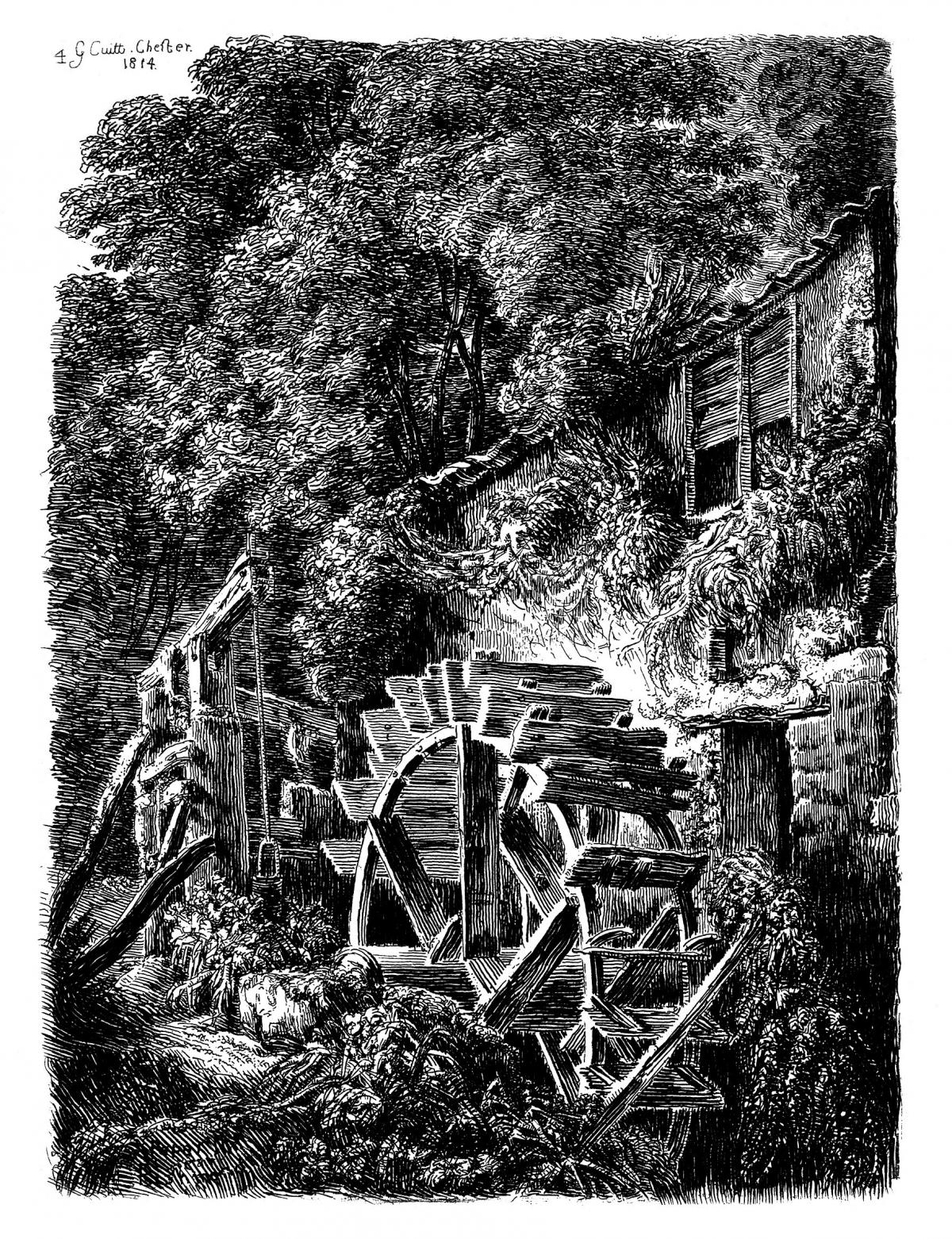

Out the back, George had his engraving studio. He coated a copper plate with wax and used his needle to scrape through the wax and scratch the copper underneath. Then he doused the plate in nitric acid, the acid eating into his scratch marks but leaving the areas protected by the wax unscathed. The plate finally went onto a heavy press to produce the print.

George established a lucrative sideline with his well-regarded prints of buildings and scenes from Chester and north Wales.

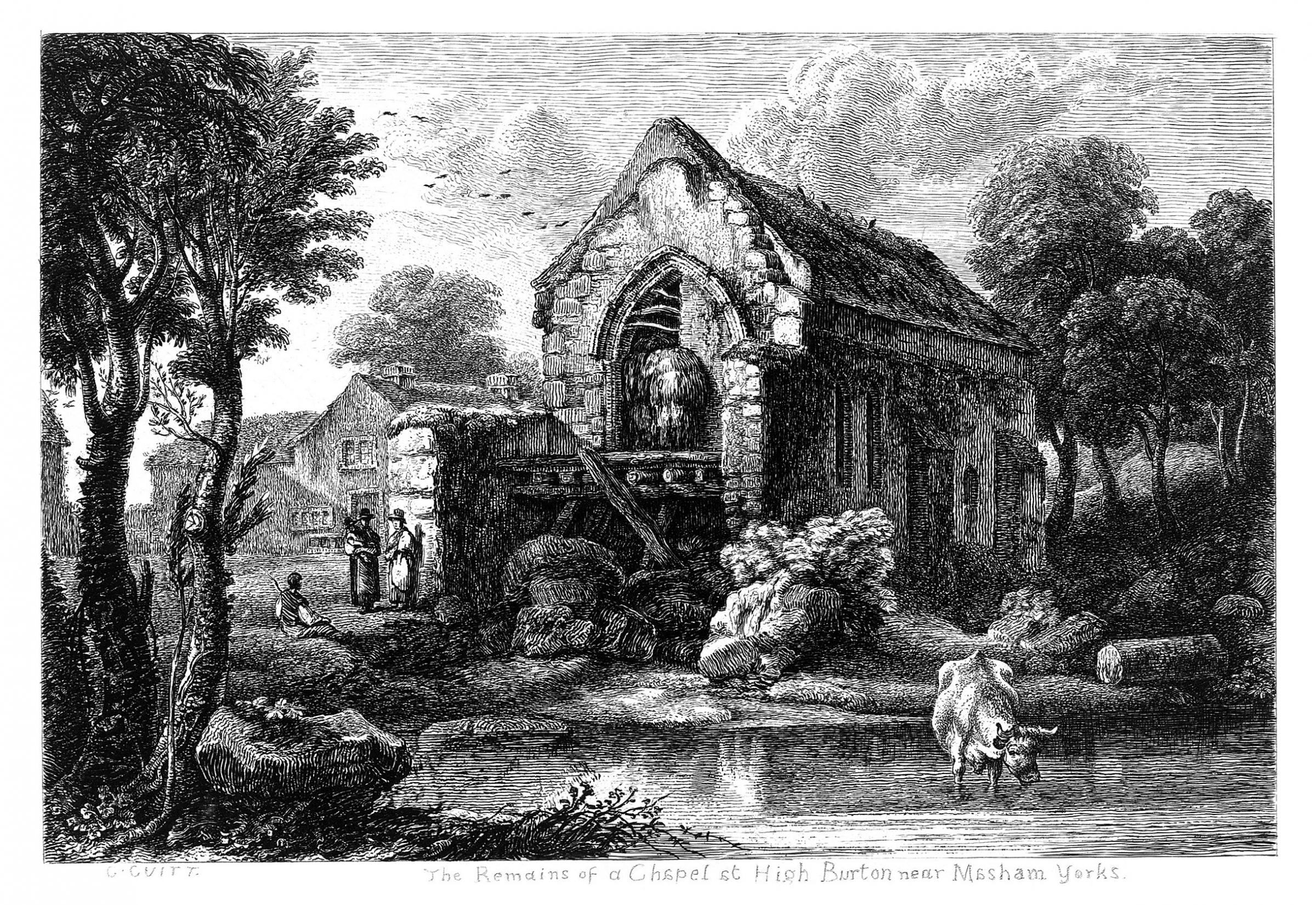

The Remains of a Chapel at High Burton near Masham Yorks, by 1827. The only known view of a chapel which had been part of the Wyvil family's estate (Bree 2.79, Cheshire Archives and Local Studies)

In 1818, his parents back in Richmond died within a month of each other, and he then suffered “a very serious attack of illness”. He stepped back from his teaching commitments and began building a new home in Millgate, Masham, which he and Catherine moved in to in 1821 – it was close to her parents and it enabled him to rejoin his wealthy Georgian Richmond set of friends.

Over the next decade, he produced his finest engravings of the ruinous abbeys of Yorkshire, including Fountains, Easby and Rievaulx, although the fumes and the dangers of the acid made it an unpleasant process.

As the 1840s wore on, George became increasingly interested in his garden – his flowers and fruit were renowned throughout the dales. In 1847, he gave up engraving and sold his plates and his copyrights to a London publisher, Angelo Nattali, who published a remarkably lavish volume of 73 etchings that was so successful it went to a reprint.

Fountains Hall, 1822. A remarkably accurate work by Cuitt, completed by an old lady bent double on the left. In angle and composition, it is very similar to several Piranesi prints of Rome (Bree 2.57, Cheshire Archives and Local Studies)

George died in Masham in 1854, and was buried in the churchyard at the bottom of his garden, followed by Catherine 16 years later. They didn’t have any children, but his nephew, William Ayrton, became the champion of the “Yorkshire Piranesi”.

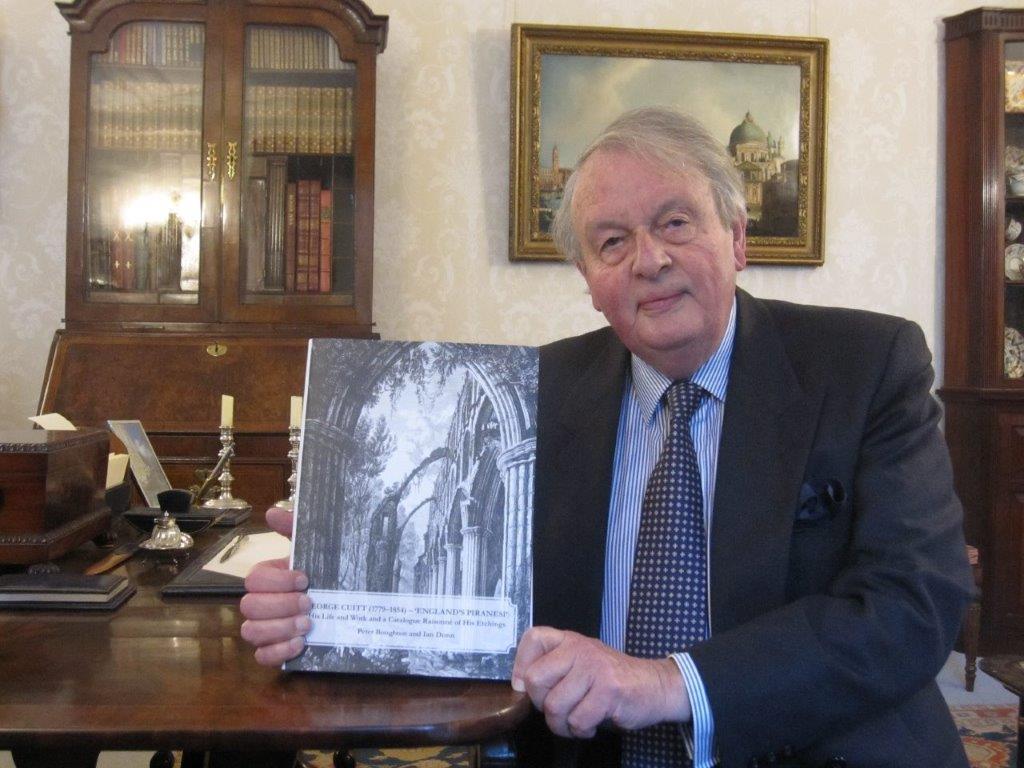

More recently, Dr Peter Boughton, keeper of art at Chester’s Grosvenor Museum, has also championed George Cuitt and, starting with the works belonging to the museum, began cataloguing his career.

Peter Boughton, who spent more than 20 years cataloguing George Cuitt's works

Sadly, after nearly 30 years work, Dr Boughton died in 2019, aged 59, but his project has been completed by Ian Dunn, the former Cheshire county archivist, with the publication of this handsome book dedicated to one of the finest etchers, and most original artists, this country as ever produced.

Ian Dunn with the new book on George Cuitt

Not only was his needle “rich and daring”, but his buildings were accurate and full of atmosphere and drama, while his detail was exquisite and his foliage to die for.

His nephew and champion Ayrton said: “They are marvellously true and forcible pictures of the scenes they undertake to convey, but the charm is they are something more. There is poetry in them as well as prose.”

Back of the net for the Yorkshire Piranesi!

George Cuitt (1779-1854): “England’s Piranesi”. His Life and Work and a Catalogue Raisonné of His Etchings, by Peter Boughton and Ian Dunn (University of Chester Press, £35 hardback)

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here