“The collision came like a crash of thunder,” reported the Darlington & Stockton Times on November 5, 1892. “In an instant, the engine and the front carriages were a chaotic heap of splintered woodwork and broken metal, with, unfortunately, men and women mixed up in the mass with the life crushed out of them.”

The disaster between Northallerton and Thirsk was caused by signalman James Holmes falling asleep for 13 fateful minutes at the levers of his signalbox. He awoke to find a goods train laden with iron stationary outside his box with the Flying Scotsman, full steam ahead at 60mph, bearing down on it.

“I knew what was up, but it was too late,” he said, “and all I could do was to wait for the crash.”

Ten people were killed, and James was eventually found guilty of manslaughter, although he was given an absolute discharge as his tragic circumstances became clear.

A reporter who encountered him shortly after the crash wrote: “The poor man is utterly prostrated and is even said to be partially unhinged mentally in consequence of the acute agony of mind resulting from the death of his child followed within a few hours by such an awful calamity.”

James, 27, told the reporter that on November 1, 1892, he had finished his 12 hour overnight shift in the signalbox in the Manor House Cabin four miles south of Northallerton at 6am. He had walked home to find his youngest daughter, Rosa, seriously unwell. The infant was placed in bed beside him but he got no rest as she began fitting. He then walked many miles desperately trying to find a doctor, but when he arrived back, she was dead and his wife was inconsolable.

Otterington station and signalbox, where James Holmes sought help after Rosa died, but was told there was no one to work his shift

At about 6pm, he walked to Otterington station, just south of Northallerton, and reported to the stationmaster that he was not fit for duty having not slept for 36 hours and wished to be at home with his wife. The stationmaster cabled his superiors asking for a relief signalman – but not explaining James’ terrible circumstances – but none was available.

James said that he would do his best, although he repeated that he did not feel fit for work.

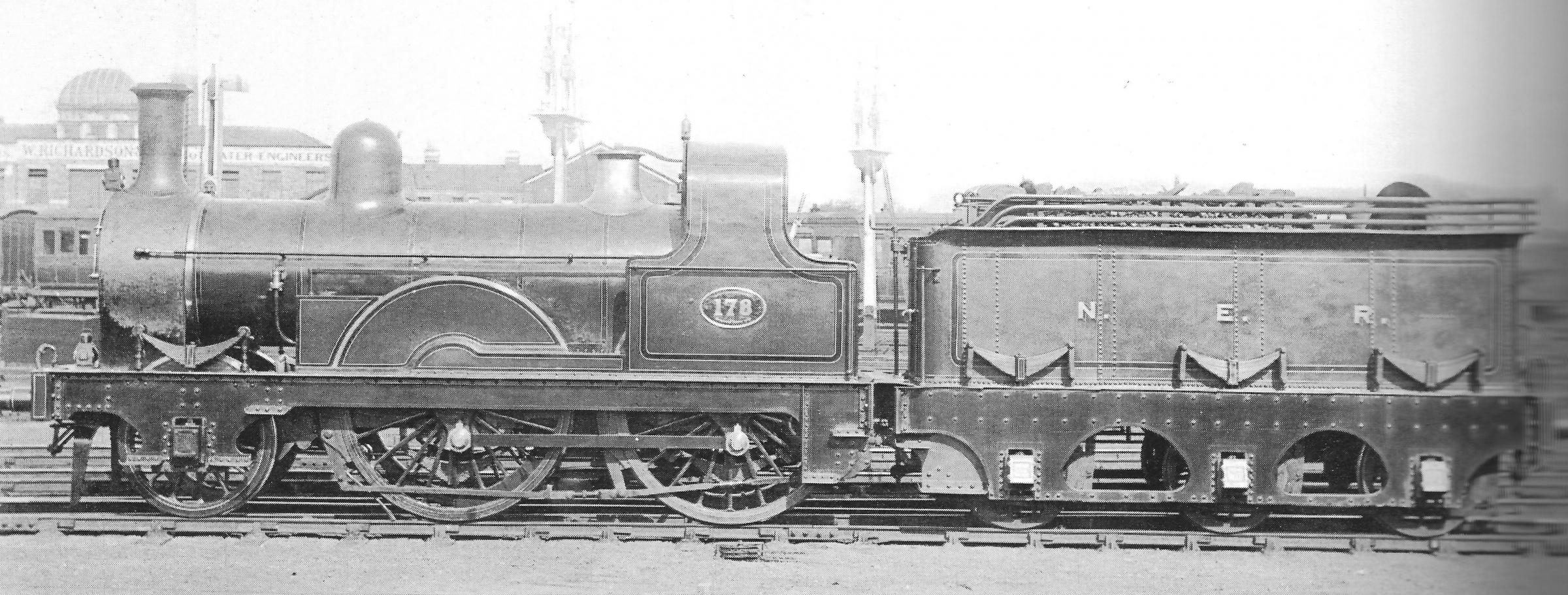

It was a confused night, as James was seeking confirmation that his mother had arrived by train from York to comfort his wife, and because the Flying Scotsman was so full it was split into two trains. The first sped through the fog past his box at 3.38am, but the second part – pulled by NER locomotive number 178 – was delayed and so the regular Starbeck goods train, from Middlesbrough to Harrogate, was allowed onto the line.

South Otterington church: we believe that Rosa was buried in the churchyard beneath a headstone which had its inscription on the wrong side compared to the others because she had not been baptised. Picture: Google StreetView

Then James, who had by now been awake for nearly 46 hours, was “overmastered by sleep”. When he awoke, disaster was inevitable – and death was random.

Alexander Mackenzie of Edinburgh had been with his young wife in a carriage at the time of impact. He came to on the tracks, stumbled from beneath the wreckage, was taken by rescuers to a nearby cottage for a cup of tea and then returned to the scene to search for her.

NER No 178 standing at Darlington's Bank Top station. It was involved in the Thirsk crash of November 2, 1892, and the brass ornament was made out of its damaged pipes when it was undergoing repairs at North Road shops

“He saw his wife lying with her arms outstretched above her head and with a heavy beam pinning her down by the waist,” said the D&S Times. “He called her but she did not reply and he came to the agonising conclusion that she was dead.”

As he approached, the wreck caught fire and the last he saw before he collapsed was flames engulfing her.

“It may be safe to assume that all victims with one exception – that of a child who died in her rescuer's arms on the way to Thirsk – were spared all the horrors of a lingering death,” said the D&S.

It was referring to five-year-old Lottie Hamilton of Dumbartonshire, who was at the start of her journey to Australia with her aunt and uncle who were both killed. Lottie was seriously injured in the impact and then had her clothes burned from her in the fire – she was carried out clutching her favourite doll, whose head had melted away, but could not be saved.

And yet those in the Pullman sleeping car, which was the third carriage behind the engine, had a miraculous escape. The crash catapulted the sleeper off its wheels so that it flew over the upturned locomotive and landed toilet end first. The toilet was destroyed, but those snoozing inside – including the Marquis of Tweedale and the Marquis of Huntly – were completely unharmed.

The D&S said that large crowds of sightseers began gathering the following morning to marvel at the flying carriage and at the ghoulish sights before their eyes.

“Thousands watched the men shovelling through the ashes,” it said. “Here and there the link of a human vertebrae, a jaw bone with the teeth still fixed in it, and other osseous remains were raked out and placed reverently in a heap.”

Indeed, the “steel busks of the corsets” of Mrs Mackenzie and the other lady to die, Miss McCulloch, were the only things that could be salvaged of them.

“This was all that remained of some who had gone forth full of life and hope and fearing no danger,” said the D&S.

How Mr McKenzie, lying injured in a cottage at the nearby Manor House Farm, and Mr McCulloch, being treated in a hotel near Thirsk station, felt when they read their papers can only be imagined.

This was, said the D&S, “a terrible railway accident which possesses some features of horror not often equalled in the annals of railway disaster” and after Signalman Holmes’s absolute discharge, the railway company, and the Otterington stationmaster, were strongly criticised.

We tell this story because Mel Holmes, from Bishop Auckland, got in touch about a handmade brass ornament which has been in his possession for many years but all he knew about it was that it had come out of the North Road railway workshops in Darlington.

Mel Holmes' commemoration of No 178 probably made from its brass pipes in Darlington North Road shops

As well as featuring Locomotion No 1, from 1825, it is a likeness of North Eastern Railway loco No 178 and includes the date, November 2, 1892, of the Manor House Cabin accident.

After the accident, No 178, which had been built in Gateshead in August 1875, was taken to North Road for repairs, and we believe a railwayman fashioned the brass ornament from the engine’s broken boiler tubes. This was not an uncommon artistic practice – brass rolling pins were also made from old engine tubes.

After its repair, No 178, which had also survived a derailment near Berwick in 1880, returned to service and worked until it was scrapped from Barnard Castle in 1922.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here