Here stands my statue carved in stone

To mind ye living I am gone

He cometh forth like a flower and is cut down.

Be thou faithful unto death and I will give thee a crown of life.

THIS is a message from beyond the grave from George Hopper, who lies in an amazing tomb in Barnard Castle churchyard, having died at the tender age of 23 in 1725.

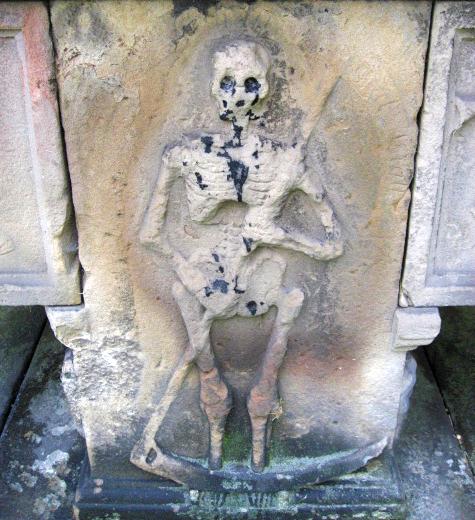

George Hopper's tomb outside St Mary's Church, Barnard Castle. Picture: Johanna Ungemach

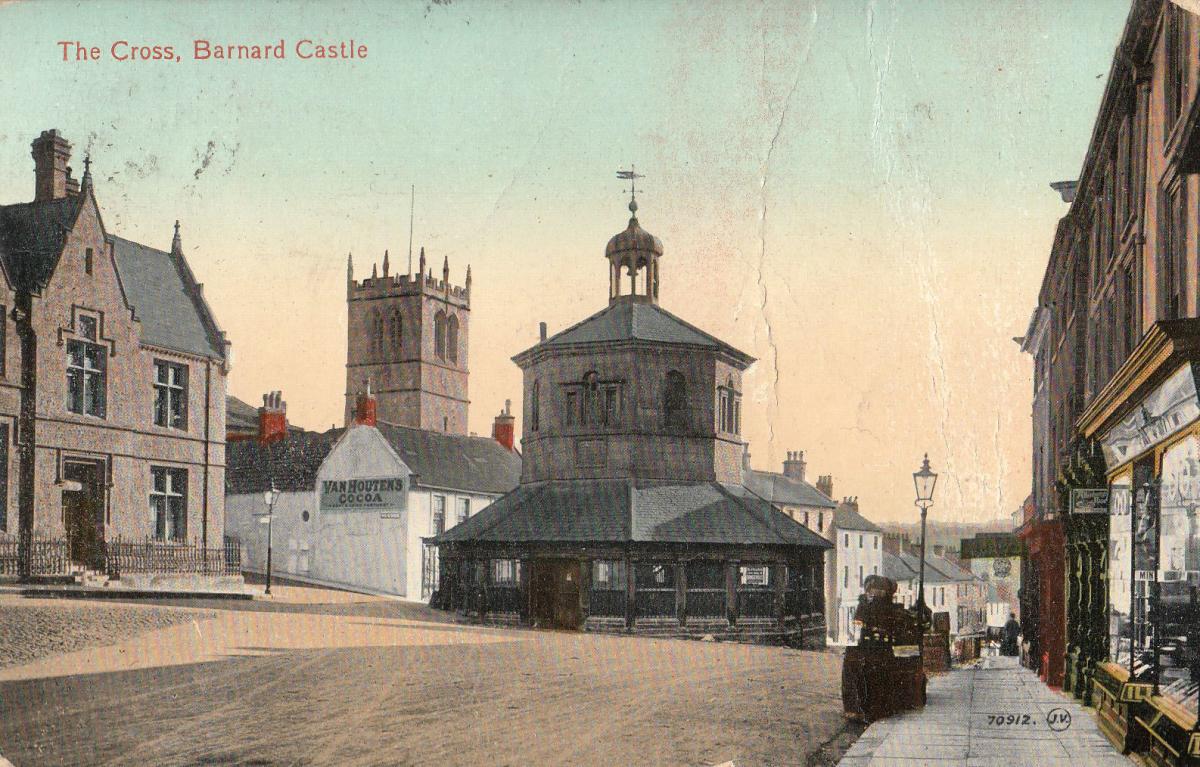

The church is currently hosting a festival of art, music and history to commemorate the restoration of its stained glass windows – and George’s tomb will certainly feature in the Gruesome Graveyard tour which is being held on Saturday and Thursday for children, and perhaps in the guided historical tours for adults which are being held every day until July 23.

The poem is on the table top of George’s tomb, and reminds the living that always they can hear, time’s winged chariot drawing near.

On one end of the tomb is a carving of George in the prime of life (above). When the carving was fresh nearly 300 years ago, it was painted so George, in his cocked hat, was wearing a blue coat and yellow breeches, and carrying a red rose.

He was clearly a fashionable man about town, and his face must have been painted, too, as in 1834, he was described as having “cherry cheeks”.

But walk to the other end of the tomb...

...and there is George in a very different guise (above). A carving shows him transformed into a skeleton – perhaps once painted black and white – and now, instead of a rose, he carries a scythe, like Death himself.

And the legend on this side reads: “Death cuts down all, both Great and Small”.

It is a grisly tomb, and in times past, visitors to the churchyard were warned to be careful how they looked at it because if their first glimpse of it was of the skeleton with the scythe then as sure as eggs were eggs, the Grim Reaper would soon be calling at your door.

Just as cruel death took its toll on George, so wicked time has taken its toll on George’s tomb.

The paint has worn from the stonework, and the legibility has weathered from the writing.

But you can just about make out another ditty in the stonework that shows that as well as being a sobering reminder about the inevitability of death, the tomb carries a hopeful message of life after death. It says:

When the shrill trump of God shall pierce

The Secret chambers of the Dead,

And rowse the Sleeping Universe

From out their owze, or dusty bed,

Such bright rewards will Vertue have

When waft by angels, She may Sing

Boast triumph now, insulting grave

Relentless Death! where’s now thy Sting?

The tomb also tells us that George was the son of Humphrey Hopper of Black Hedley, near Shotley Bridge in north Durham – Humphrey’s mid 18th Century farmhouse, which may have been George’s boyhood home – is now a listed building.

George came to Teesdale to look after the family’s estate at Marwood, to the north of Barney. It was probably at Wool House Farm, just outside the town, that the Grim Reaper caught up with him.

George was buried in the churchyard but, nine years later, the rector decided he deserved something better and his body was disinterred and placed in the painted tomb in the south-west corner of the church.

However, on July 11, 1748, a fire broke out in a barber’s house and consumed two other residences before the fire engine, brought from Raby Castle, could extinguish the flames. Lord Barnard then gave the engine to the town, but the only place big enough to stable it was the church – in the south-west corner.

This led to a series of legal cases, heard once in Durham and twice in York, with the churchwardens fighting the Hopper family to get George moved. Finally, a judge ruled that the churchwardens were pursuing “a very trifling and vexatious suit” and ordered them to pay £50 costs.

George was allowed to rest in peace, although as the town’s fire engines had to be placed inside the north door and in the south porch, there was no access into the church for the worshippers, so a third door, in the west, had to be knocked through.

In 1870, with St Mary’s Church in a dangerous state, a restoration programme began. The fire engines were moved out, the west door was blocked up, the tumbling tower was shored up, and George and his tomb were moved out.

He now lies close to the south door, and although his paint has flecked off and his wording is wearing away, the sight of the skeleton is still a sobering reminder of the fleeting nature of life.

THE Windows to the World festival at St Mary’s Church, Barnard Castle, commemorates the restoration of the church’s stained glass windows, which date from the late 19th Century, with an exhibition of contemporary stained glass by six leading modern artists. It is free and is open all day.

The windows have been restored by Jonathan and Ruth Cooke, of Ilkley, and their son, Tristram, is a counter-tenor in the choir at Westminster Abbey. He was working with them during lockdown and was so taken by the church that he has arranged three concerts for next week.

Plus there are tours everyday at 11am and 3pm (12.30pm on Saturday and 1.30pm on Sunday), plus children’s events like the Gruesome Graveyard tours on Saturday and Thursday at 1pm.

Full details of the festival, which runs until Friday, July 23, are on the church’s website: stmarysbarnardcastle.org.uk. Many events need to be booked, although there are some walk-up places for the tours.

SO, when the shrill trump(et) of God sounds, it will rouse the dead from “out their owze, or dusty bed”. What does “owze” mean?

The Oxford English Dictionary reckons it could come from “ooze”, which is the muddy slime at the bottom of a riverbed, or the disgusting liquor made of bark that was used in the tanning process.

Or, it says, it is the 18th Century Devon dialect for “house”. The OED doesn’t list any Durham versions of the word, although in Yorkshire at that time, it says the following pronunciations of “house” were in circulation: hause, haase, hahse, hoos, ahs and oos.

Why didn’t the stonemason choose one of those? Was it because none of them rhyme sufficiently with “rowse”, or could it be said that, despite all his clever carvery, he didn’t know his ahs from his elbow?

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here