There's new hope for racing relics with a nationally important story, as a book published this week tells. Chris Lloyd reports

ON the moors above Richmond, with panoramic views east to the hills and coast of Cleveland, are the remains of the world’s oldest surviving racecourse grandstand.

It was designed by Yorkshire’s greatest Georgian architect and it was the first in the world to enable in-race betting. In its heyday 200 years ago, it was the fashionable place to be seen as the wealthy showed off their finery on race day.

Nearby on this elliptical stretch of gently undulating grassland stands the square stone judge’s box – the oldest in the country – beside what was once the finishing line.

Over the years, the course has seen many battles, from racehorses snorting their way neck and neck to the break the tape, to Captain Dawson and John Wycliffe duelling over Mrs Dawson who was “a fine looking woman”. Last week, after great debate about curtilage, a Planning and Regulatory Sub-Committee of North Yorkshire County Council agreed to de-register the buildings as common land.

Since the first race was held on Low Moor in 1765, the exact ownership of the grass beneath the horses’ hooves has been questionable, but last week’s meeting reversed a decision made in 1968 so that now a solution can emerge to enable the historic relics to be saved.

In light of the decision, a book has been published this week telling the fascinating story of the racecourse. It is based on research by Professor Mike Huggins of Cumbria University, a world authority on racing because those relics up on the windswept moor really are that important.

Richmond was a racing centre since at least 1512, although no one knows for sure where its first “high moor” racecourse was situated.

In 1765, the racecourse was moved to the pastures of Low Moor, which, despite its name, has an elevated position. This was a commercial decision, driven by the two big industries associated with racing. Firstly, there were the stables, where sturdy North Riding mares were with crossed fast Arabic stallions to create thoroughbred racehorses that built up stamina training on the peaty moorland, and then there was the hospitality with Richmond’s hotels and pubs coming alive on race day.

Richmond Corporation – or council – invested much in levelling and draining the pasture to create a 1.5 mile elliptical course with a five furlong straight.

The expense was rewarded in 1775 when George III decreed that the annual prestigious race for the King’s Plate would be held alternately at York and Richmond.

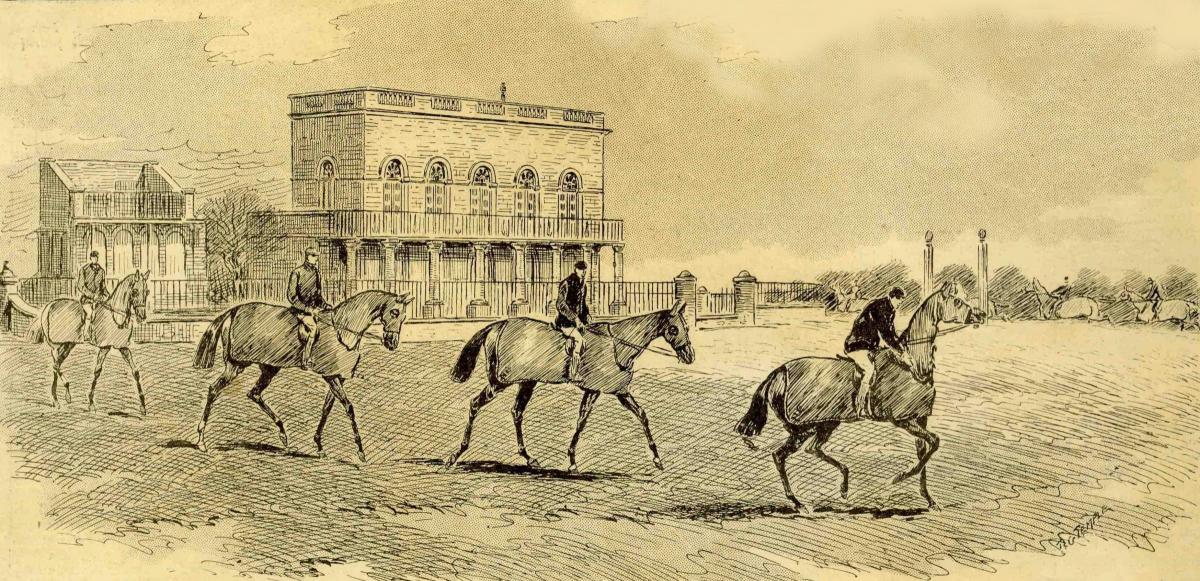

To prepare for the first race in 1777, Richmond instructed John Carr to build a suitable grandstand. He was the greatest architect of his day, renowned for Harewood Hall near Leeds. Locally, he designed Northallerton prison and practically every bridge from Bainbridge through to Croft.

Plus, in 1747, he had designed the world’s first public grandstand at Wakefield racecourse. Early grandstands overlooked the finishing post so the crowd got the best view of the closing moments but they often couldn’t see the rest of the course. At Richmond, Carr used the natural rise of the land to position the grandstand so that the finish could still be seen but all of the course was laid out before the spectators.

Most races were more than four miles long, nearly three times round the course, and lasted seven minutes, so with the horses almost always in view, in-race betting became possible for the first time.

The grandstand cost about £1,300 to build, with Charles Dundas of Aske Hall, a breeder and owner, leading the way, but townspeople also paid five guinea subscriptions for which they received a silver medallion that granted them lifelong access to the grandstand.

Richmond’s three day meeting in early September became one of the great dates in the Georgian social calendar. The best racehorses were – slowly – walked to take part and the town filled up more than a week in advance. Stately homes from miles around were full of upper class guests, and there were balls and the theatre to keep them entertained.

The highlight of the meeting was the Gold Cup, a race for a trophy that cost the townspeople 100 guineas each year to make. The glittering prize was paraded from the town hall, past thousands in the crowded streets and placed in front of the stand, ready for the race.

Non-horse related activities also took place on the racecourse. For instance, around 1780, when Capt Dawson found a love letter that his friend Wycliffe had written to his wife, he challenged him to pistols at dawn at the course. Wycliffe was seriously injured, and the ball could never be removed from his body, whereas Dawson fled from town never to return, taking his “fine looking” wife with him.

As the 19th Century wore on, the railways sucked the wealthy in to London, and so the fashionable racecourses – Epsom and Ascot – grew at Richmond’s expense.

Social attitudes changed. Whereas gambling had once been seen as a way of boasting about your wealth and bravery, religion now frowned upon it.

Other aspects of the frivolity became concerning. “On Tuesday, the Grand Stand on the Race Ground was…a place of more than ordinary profligacy and drunkenness, till many were scarcely able to find their way home,” fumed one angry Richmonder in October 1844. “I am informed that one person was in such a state that he might have perished by the way had he not been taken in a state of insensibility to a public house in the town, where a medical gentleman was under the necessity of applying a stomach pump in order to save his life.”

When Lord Zetland’s horse Voltigeur won the Derby in 1850, eight or ten old timers were said to have drunk themselves to death within 12 months such was the enormity of their winnings.

With the drinkers and the gamblers came the pickpockets and the prostitutes. In a bid to recreate an air of exclusivity on the racecourse, in 1883, Lord Zetland built himself a new grandstand, designed by Darlington architects Clark and Moscrop, beside the old one, but rural racecourses were now in terminal decline. The final meeting at Richmond finished on August 7, 1891.

Since then, the fabulous setting has had many uses, particularly military ones – Richmond’s nuclear monitoring bunker was on the edge of the course until 1991 – and also dogwalking ones.

Over the course of time, the grandstands slowly fell down. In 1969, Richmond council wanted to demolish them for safety reasons, but North Yorkshire council refused because of the historical importance.

And so the buildings continued to fall down.

The one constant in the story is the Richmond Burgage Pastures Committee which, even before the advent of racing, was in charge of the grassland where the burgesses – wealthier townspeople –grazed their animals. After a decade-long battle, which included trying to get a Private Members’ Bill through Parliament to amend an 1853 Act, the committee has de-registered the tumbledown buildings and so now can seek to find partners to restore and repurpose them.

With panoramic views, fine walks, bracing weather and a splendid Georgian story to tell about a national first, a tearoom in the grandstand would surely become a popular destination.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here