LAST week, we told of the wedding 150 years ago of Lord Ernest Vane Tempest, the younger son of the 3rd Marchioness of Londonderry, of Wynyard Hall, and Mary Hutchinson of Howden Hall, the daughter of a Stockton iron merchant.

The ceremony, witnessed by hundreds of local people, took place at St James’ Church in Thorpe Thewles, and the D&S noted how as the bride arrived “the sun for a moment shone feebly through the mist, and this omen of a happy future was hailed by a flattering cheer from the vast assembly”.

In searching for omens in the weather, perhaps the D&S’ reporter was showing his own forebodings as he must have known of the colourful character of the bridegroom.

Ron Tempest, from the Wynyard Estate, has kindly filled us in on the technicolour details.

Lord Ernest fell out of school at the age of 18 and ended up as a private in the army. Family connections earned him a commission as an officer, but when he was stationed at Windsor, he formed a romantic attachment with a young actress at the Gaiety Theatre.

He forced his way into her dressing room, and when the theatre manager objected, Lord Ernest punched him and threw him down the stairs.

In disgrace, Ernest resigned from the Life Guards, and went opal mining in Australia.

When the scandal had died down, he returned and became a lieutenant in the 4th Dragoon Guards. He served in the Crimean War, but when back in Brighton he was involved in “the disgraceful ragging of two young cornets”.

Two younger soldiers were forced to take part in an initiation ceremony. One was found in a fountain in his nightshirt while the other, the son of a prominent clergyman, was pinned down on a sofa and Ernest cut off his whiskers.

Ernest explained his actions by saying he had taken exception to the soldier’s “peculiar English and pronunciation of the letter h”.

He was drummed out of the army for a second time, and when the shaven soldier pressed assault charges, he was forced to hide in his mother’s house in Park Lane, London, to avoid the summons. He was declared an “outlaw” and fled abroad, apparently without paying for some jewellery. The Times newspaper said he was “of Strephonic tendencies”, which is undoubtedly true although neither the Oxford English Dictionary nor the internet is able to provide a definition for the word “strephonic”.

Somehow, Ernest ended up in the American Civil War in the early 1860s, fighting under the name of “Colonel Stewart” for the Union side in several of the epic battles on the River Potomac.

By now estranged from his family in Wynyard, he hadn’t spoken to his mother for years and failed to attend her funeral in 1865. However, by 1868, he must have mended some fences because he was back, and standing as the Conservative candidate to be the first MP for Stockton.

He lost, polling 25 per cent of the votes in a two-horse race.

But he won the hand in marriage of Mary, and when the sun broke through the clouds as she left the church, did it suggest that at the age of 33, he was now entering a more settled period of his life?

They moved to Scarborough, and had a son, Charles, in 1871, but…

“They seem to have been estranged quite early with newspaper reports of a relationship between Mary and a mysterious Mr Hungerford, who was described as a close friend of the Prince of Wales who later Edward VII,” says Ron. “Ernest attempted to knock his head off!”

Then he adds as an aside: “There seems to be a bit of a theme here as his brother’s wife, Susan, allegedly had an affair with the Prince of Wales himself, giving birth to a daughter in secret who then disappears from the records – but that’s another story.”

Indeed it is.

He continues: “When Ernest died in Scarborough in 1885 aged 49, his obituary did not mention a wife at all.

“She apparently lived in the Scottish borders and survived him by five years – her death certificate says she died of pneumonia and mental instability, poor woman. Both are buried at Thorpe Thewles.”

Charles, their son, lived at Howden Hall his son, Charles, was shot down over northern France in 1917 while serving in the Royal Flying Corps. He was captured but died within hours. There is a memorial to him in the church in Norton.

THE higgledy-piggledy land around the church at Middleton Tyas is “tossed in strange confusion” by the copper workings on which the village’s prosperity was based.

Indeed, the village’s big mansions, one of which is the subject of a planning dispute as the D&S Times reported last week, were built by the Hartleys, the copper mining magnates.

Leonard Hartley, the head of the family, lived in East Hall, which is hidden by tall, secretive walls – just as well, perhaps, as three tons of stolen copper ore was discovered concealed in its cellars and gardens in 1742. It clearly wasn’t Mr Hartley’s copper ore, as his mines weren’t then operational, but the case against him was never copper-bottomed enough for it to go to court.

Within years, he had sunk scores of shafts around the church and was soon digging up his own copper. By the middle of the 18th Century, he’d helped turn Tyas into a boom town. As many as 400 immigrants flooded in, from Derbyshire and Cornwall, and, fuelled by the village’s 20 pubs, the illegitimate birth rate soared to ten per cent.

The copper seam was patchy, but where they found it, it was said to be the richest in Europe. It was, though, troubled by water, and soon a couple of horse engines and a steam engine had been built to pump out the shafts – the remains of a stone engine house can still be seen beneath the church.

Momentarily, it was a lucrative industry: in one summer alone, 400 tons of copper was mined and sold at £52 each (that’s at least £10,000-a-ton in today’s values).

West Hall was the Hartley’s other major property. Overlooking the green, and subject to the planning disagreement, it was built in 1705 and was enlarged as the family fortunes grew.

So large did they grow that in 1770, Leonard’s son, George, was able to commission leading York architect John Carr to design Middleton Lodge for him – it is now an extremely elegant “award-winning hotel, restaurant and wedding venue”.

Yet it was a short-lived boom. When the steam engineer Matthew Boulton visited in 1783 on his way home to his Soho works in Birmingham, he noted that work had stopped in most of the shafts and that it was “not a practical proposition” to restart it.

Indeed, a new vicar had arrived and ordered that the ugly spoilheaps on the way to the church should be levelled and so today, St Michael’s is approached by a long avenue of trees. The fields all around still bear the pockmarks and the mansions still give the nod to a time of great prosperity.

From the Darlington & Stockton Times of January 25, 1919

REPORTING from an Aysgarth Rural Council meeting held in Bainbridge 100 years ago, the D&S reported that Sir Hugh Bell, the Lord Lieutenant of the North Riding, had written to the council saying that there were a large number of war trophies to be handed out.

These included “captured German rifles, carbines, bayonets, machine guns and trench mortars”.

The councillors were immediately enthusiastic. The chairman, FS Graham, said Bainbridge should get a large piece of captured kit to go on its green, saying it was a “desecration” when the two old guns had been removed from the village’s heart.

Another councillor went further, and moved that Bainbridge should apply for two trench mortars.

Mr Metcalfe from Hawes demanded that his town should also have one, and he wanted some smaller trophies to decorate the Market Hall.

Mr Kirkbride went further, saying that as well as Bainbridge, West Burton and Turfy Top should be decorated with such armaments.

Turfy Top appears to be at the western end of Hawes – the B6255 goes up Turfy Hill on its way to Widdale.

So councillors in 1919 thought it would be a good idea to have a German gun placed at the highest point, ready to rain down mortars at a moment’s notice…

Last year in this space, we told how many places did receive trophy guns – Hutton Magna, for instance, because it had sent the most men in all Teesdale off to war – but they quickly became hugely unpopular. Returning soldiers hated the sight of the guns that had been firing at them for four years, and grieving relatives wondered whether the gun mounted in triumph on the village green could have been the one which had killed their poor Tommy. The trophies were deliberately disappeared from village greens, with the larger ones being rolled into nearby lakes.

January 30, 1869

SALTBURN pier was nearing completion, but the D&S reported how 150 years ago the engineer, John Anderson, was sued at Stokesley County Court for £3 6s 8d by a Mr Henderson, of Middlesbrough, who had been contracted to sink a shaft for a new lift.

However, when he’d got down to really hard rock, Mr Anderson had told him he hadn’t made it wide enough, “on which account the plaintiff left off sinking and claimed the above amount for the work done”.

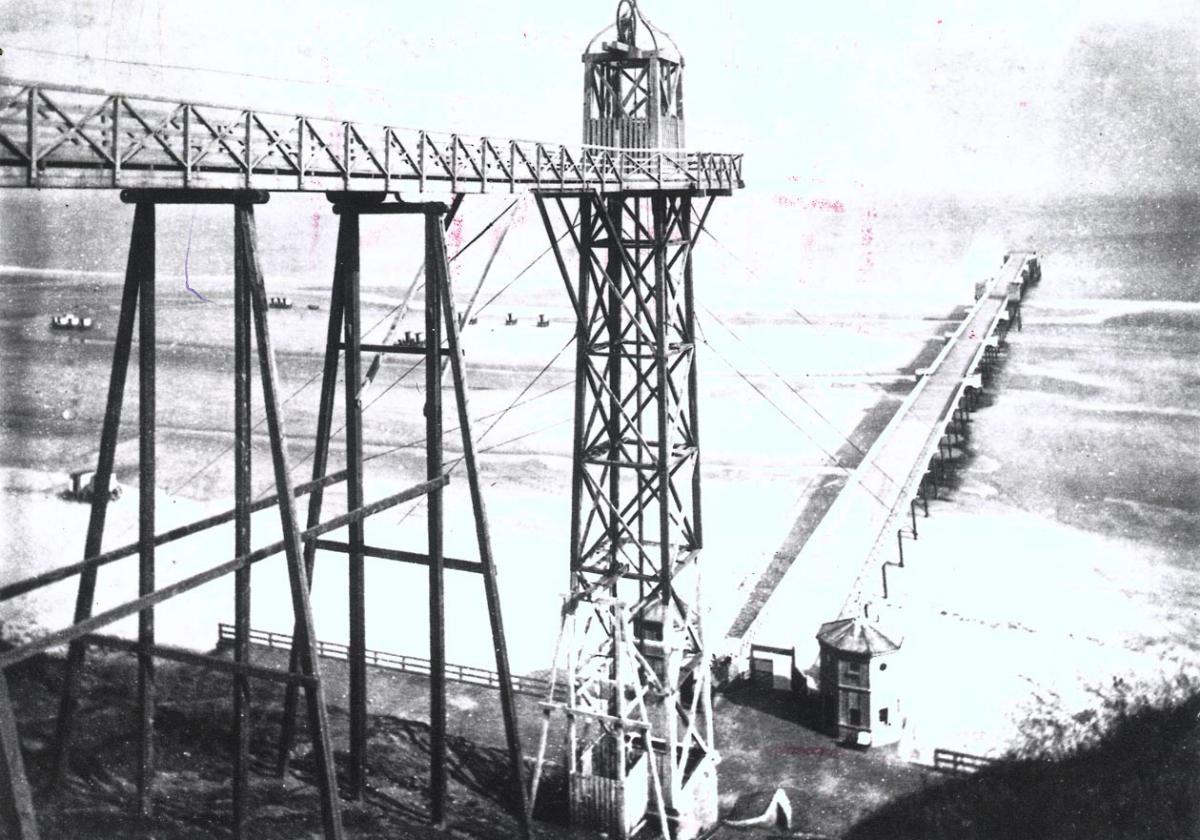

The judge awarded him only £1 8s 9d, and Mr Anderson seems to have abandoned the idea of a shafted lift and instead started work on the remarkable cliff hoist which was opened the following year. People walked from the clifftop out on a shonky-looking gantry and then descended in a cage to the beach. It lasted for 13 years.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here