HORNBY CASTLE didn’t just have one icehouse, as we suggested last week. It had three!

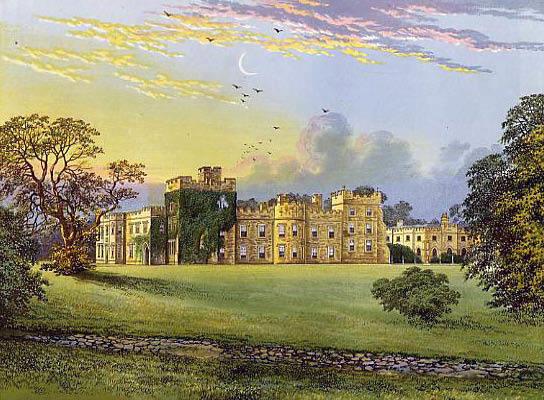

The castle is between Bedale and Catterick, and although it strikes a fabulous silhouette on its raised ground surrounded by a deerpark, it is today a shadow of its former glories.

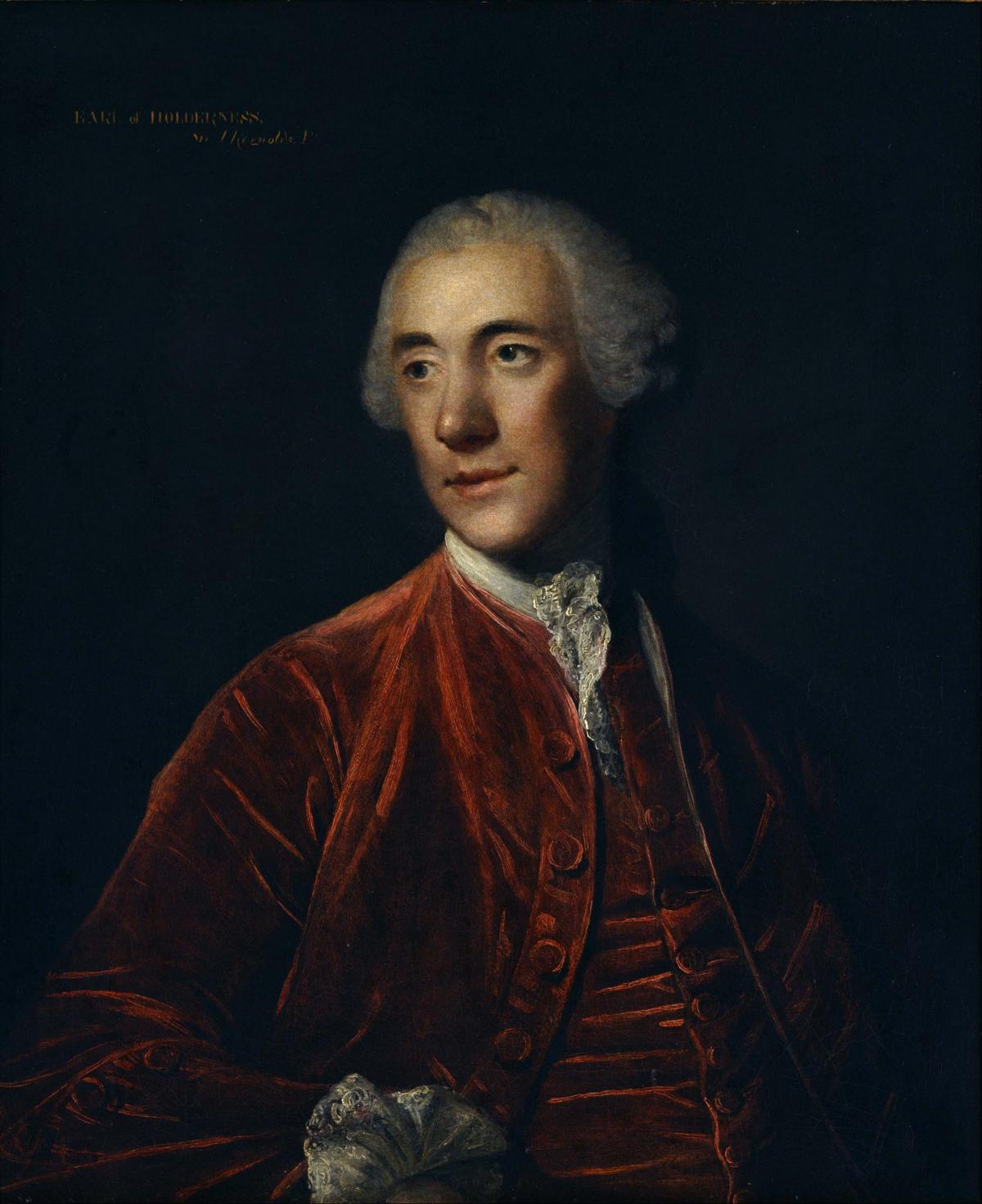

There’s been an important house there since the Duke of Brittany had a moated hunting lodge near the church in 1115, but it really became impressive when Robert Conyers-Darcy, the 4th Earl of Holderness, had the grounds laid out in the 1760s and 1770s with three eyecatching farms – known to designers as “eye-catchers” – strategically placed on ridges. He built bridges, summerhouses and grottoes, and fringed the gardens with a ribbon of ponds which looked like a flowing river.

It looks as if this parkland was designed by Lancelot “Capability” Brown, with the renowned Yorkshire architect and bridge-builder John Carr in charge of realising the designs.

“A further interesting feature is the detached Banqueting House known as the “Museum” which survives as a ruin in the park,” says Erik Matthews, who has been running a volunteer archaeological fieldwork project at the castle for 10 years. “It was designed by Horace Walpole who designed Strawberry Hill in Twickenham in London in the 1760s. If you had the appropriate credentials, the Duke would send out for supplies from the local ale house and entertain you down there!”

Perhaps the Duke, who served as an ambassador and a foreign minister to George II, didn’t know how rude Walpole was about him in his writing, where he called him “that formal piece of dullness”.

The 4th Earl died in 1778, and his heir was the husband of his daughter, Amelia, the 5th Duke of Leeds.

But the 5th Duke didn’t have much time for Hornby as not only was he Foreign Secretary but Amelia eloped with John “Mad Jack” Byron, father of the dangerous poet.

But the 6th Duke of Leeds made Hornby his principal seat. He populated the grounds with peacocks and pheasants, built an eagle house, and in 1815 he installed a waterfall and at least one of the icehouses.

“At at an early stage of our fieldwork, we recorded the icehouse, which served the house and which lies directly to its rear,” says Erik, sending a photograph of its impressive vaulted interior. “It is unusual in that it is significantly larger than the usual standard size.

“In its heyday in the early 19th Century, the Castle had two other icehouses.

“There was a second one at West Appleton, which served the dairy and was involved in the manufacture of ice creams, sorbets and other desserts for the house, and we have recently located a third one in the park which was used to supply a fishery.”

However, after the 10th Duke of Leeds, a Conservative politician called George Osborne, inherited Hornby in 1895, he became far more interested in greyhound racing, racking up great debts, than estate building as the castle began to go to wrack and ruin.

“But compared with his father and his son, the 10th Duke was a paragon of virtue!” says Erik. “The 11th Duke, his son, was a compulsive gambler, alcoholic and womaniser whose first wife was a Serbian ballet dancer.

“He had to sell Hornby in 1930 following a “no-holds barred baccarat” game on his motor yacht at Monte Carlo which he, of course, lost.

“Everything went including priceless old masters, furniture and the library which included the original manuscripts of William Congreve, the 17th Century playwright, and the earliest written account of the legends of Robin Hood from the 15th Century.

“The house was due to be demolished and the materials used for road maintenance but part of it was saved at the last minute by one of the asset strippers. This scandal led to the National Trust setting up its scheme to take on country houses and their contents.”

So what remains at Hornby Castle makes an impressive silhouette, but is in fact a shadow of its former glories when an castle owner needed not just one icehouse but three.

PERHAPS there were four!

David Shaw gets in touch to point out that an icehouse is recorded in the grounds of Crakehall Hall, near Bedale, on the Ordnance Survey maps of the late 19th Century, but it had disappeared by the time the 1913 OS map was published.

There can be few more idyllic scenes in England than the white-clothed cricketers playing on the tree-lined, five acre village green at Crakehall with the perfectly symmetrical hall as the backdrop.

From the 14th Century, the lord of the manor of Crakehall was the Conyers family of Hornby Castle, and in the early 18th Century, they built the hall as a country retreat. However, they sold it in 1732 – before the dawn of the age of the icehouse – to Miss Mary Turner of Kirkleatham, and on her death in 1763, it was inherited by Matthew Dodsworth of Thornton Watlass Hall.

He was a proper squire, dispensing justice – he became very unpopular for jailing a Crakehall pauper, Joseph Benson, for illegally fishing in Crakehall Beck only for Mr Benson to die in prison – and living surrounded by servants who a uniform of blue coats and yellow waistcoats.

Under Mr Dodsworth, who died in 1804, Crakehall Hall enjoyed its heyday, and as the golden age of the icehouse in our area seems to be 1775 to 1820, it seems likely that the fashionable subterranean structure was his work. It was located near a long, thin pond known as Long Pond, which must have been the source of its ice.

Although the icehouse has been missing from maps for a century, it can’t just have melted away. Does anything of it remain?

IN these days when statues are toppling on a daily basis, Darlington should say a word in praise of Mr Pease who stands on a plinth in High Row.

In 2008, this statue, erected in 1875, was one of 21 across the country to have their listing schedules enhanced because of their importance to the anti-slavery movement.

Four friezes on Joseph Pease’s plinth tell his life story. On one of those friezes, a slave writes the word “freedom” above the heads of a rejoicing crowd.

The Peases were Quakers, who believed that all people were equal before God. Joseph’s uncle, also called Joseph, lived at Feethams where the Town Hall is today, and from the earliest years of the 19th Century, he led a national campaign against slavery in India.

He fired his daughter, Elizabeth, with enthusiasm for the cause of fairness, and she founded the Darlington Ladies Anti-Slavery Society in the mid-1830s – it was one of the first women’s political movements in the country.

In 1840, Elizabeth was one of six women to attend the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London where, to her horror, she discovered that because she was female she was not only forbidden from speaking but she had to sit behind a bar and a curtain. This unfairness fired her further and she became a feminist, arguing that women should be equal also.

In 1853, though, she married a Glasgow university professor of astronomy who was not a Quaker. “Marrying out” was still frowned upon and so broke ties with Darlington and lived the rest of her life in Edinburgh, campaigning for women to get the vote.

In 1832, Elizabeth persuaded her cousin Joseph to break with Quaker tradition and stand for Parliament so he could further the cause of anti-slavery. He won the South Durham seat, and became the first nonconformist MP in the Commons for 200 years.

Joseph joined fellow MP William Wilberforce in campaigning to free slaves.

In his longest speech, Joseph appealed to other MPs "on behalf of their poor brethren of colour whose sufferings under the present system were of a nature to stimulate every feeling bosom to concede to them a paramount consideration”.

The speech covers 40 pages in Hansard, the Parliamentary record, and as Joseph delivered it, he became increasingly wrapped up in the emotion of it, much to the delight of the Whig MPs opposite him.

Hansard records: "He felt the inadequacy of his powers in pleading such a cause. (Here, the hon gentleman was so affected he was obliged to pause for a moment. Much cheering.)

"The house will pardon me (concluded Mr Pease) for having so long trespassed upon their attention. I am unable to go on. But when the great and solemn day shall come, when I shall myself stand in need of mercy, I hope it will be meted to me in the same measure as I am disposed to mete it to others."

Despite the ridicule, Joseph's speech was widely regarded by anti-slavery campaigners as for providing moral justification for the cause, and the Abolition of Slavery Act received Royal Assent on August 28, 1833.

Unfortunately, Wilberforce never lived to see it – he died a month earlier, just as the Stockton & Darlington Railway was taking delivery of its engine No 23.

It was designed by Timothy Hackworth, but had been built by Robert Stephenson & Co in Newcastle. It was a major step forward for the railway: Locomotion No 1 of 1825 had been able to pull 250 tons of coal per mile per hour but locomotive No 23 was able to pull 1,250 tons of coal per mile per hour, and it was the first engine in the dark green paint that the S&DR then adopted for all of its locos.

No 23 was named Wilberforce in honour of the anti-slavery campaigner.

From the Darlington & Stockton Times of June 23, 1870

THERE were high hopes of cricketing excitement in Northallerton where “the famed All England Eleven” were to take on a team of 22 players selected from the local district – plus a few ringers.

“The Twenty-two will comprise the elite of the northern amateurs, with the assistance of Guild, Lee, Clayton and Bishop as bowlers,” said the D&S Times 150 years ago. “From the well known talent of the players engaged on both sides, the game is expected to be a close one.”

The All England Eleven, known as the AEE, had been formed in 1846 and were essentially the Harlem Globetrotters of cricket. Using the railway network to good effect in the days before county and international cricket had been fully established, they toured the country, taking on big teams of locals.

The D&S suggested that they would be led by George Parr, “the Lion of the North”, from Nottinghamshire who was regarded as the best cricketer in the world, and their innings would be opened by George Atkinson, described as “one of the finest hitters that ever batted for Yorkshire” who had been born in Ripon in 1830.

The AEE was to include R Carpenter and T Hayward, who a month later would share in a record 305 partnership, and the delightfully-named Richard Daft, who was at the peak of his powers as a batsman.

Perhaps the match didn’t live up to its billing. The D&S’ match report ran to a single paragraph: “The match on Saturday resulted in a draw, there not being time to play it out. The eleven were got out for 125, 13 less than their opponents – Guild taking no less than eight of the wickets. The twenty-two had lost wicked for 28 runs when play ceased.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here