Motorsport broadcaster and journalist Larry Carter travels back more than 80 years to when some local rambling haunts formed part of one of the world’s toughest motorcycling events.

NOW that our great and illustrious leaders have sown the seeds of optimism (and tellingly, we pass our "four tests to freedom"), if we are to believe them, then life in 2021 should start to return to some semblance of normality.

Just like many thought this horrible pandemic would be over as soon as the clock struck midnight on New Year’s Eve, I have some serious reservations that, come the nights starting to get darker in late June, not all will be back to just how it was before, but we can hope.

But first, a history lesson… Back in 1938, there was another air of gloom and despondency hanging over the world as a bloke called Adolf was doing his best to do what Covid-19 is doing now, and that’s to batter the free world into submission. In September of that year and having been named Time Magazine’s "Man of the Year", the Fuhrer met with three other statesmen in Munich to redraw the map of Europe as the world barrelled inevitably towards war again.

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain, Premier Edouard Daladier of France, and Benito Mussolini of Italy were deemed the only world figures of importance to Hitler and, with the Anglo-French policy of appeasement meaning Czechoslovakia was sold up the river to join Nazi-annexed Austria, the Munich Agreement signed by both Hitler and Chamberlain, guaranteed "peace in our time". And we all know what happened soon afterwards…

However, a month or so after the most insignificant document of the 20th Century was signed, a group of people were gathering under those impending clouds of war with a contrasting outlook, in the hope things may not turn out as badly as expected.

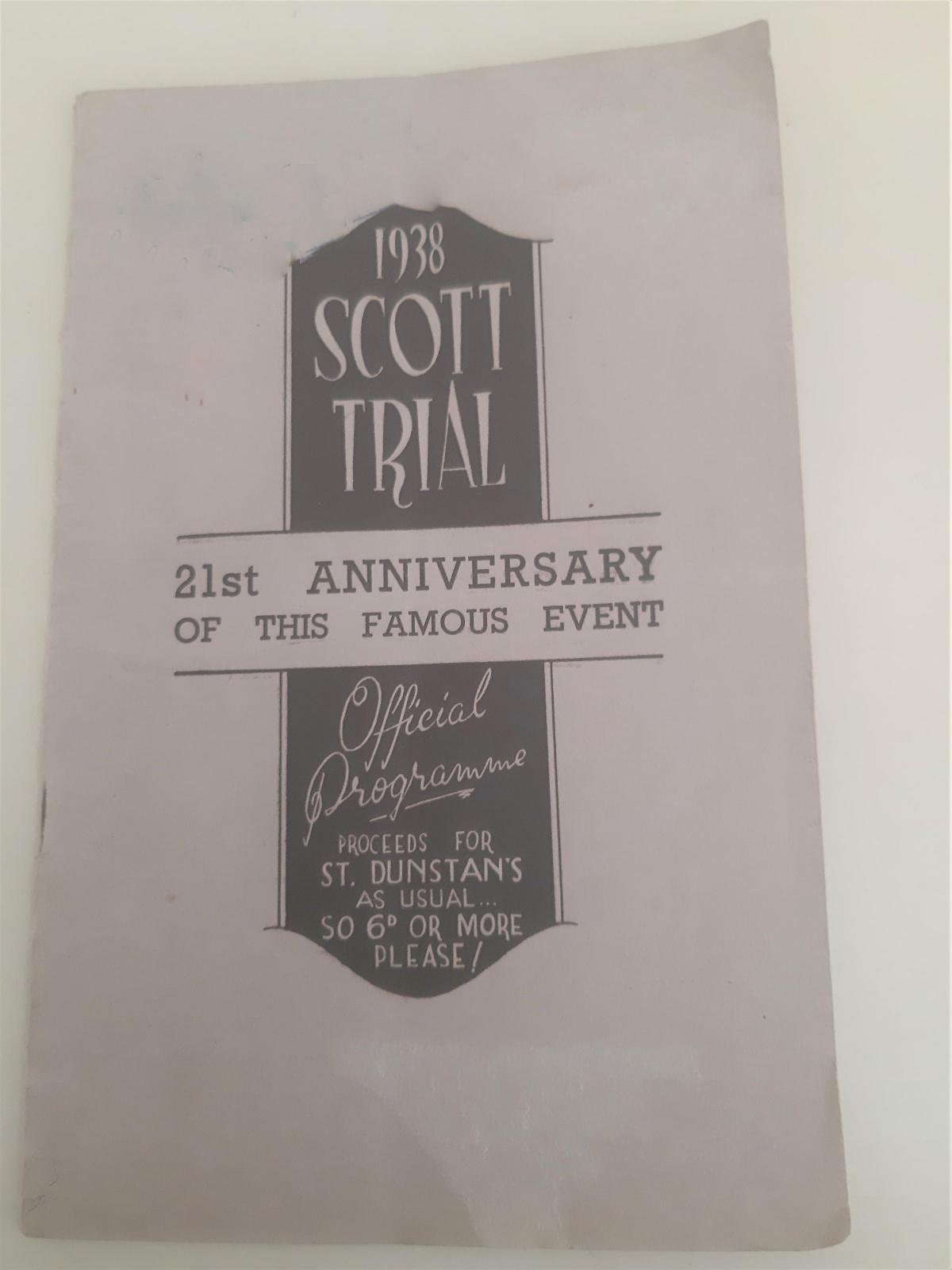

After 20 years of being based in the West Yorkshire dales near Bradford, the Scott Trial celebrated its coming-of-age in the Cleveland foothills for the first time. With new custodians Middlesbrough and Stockton Motor Clubs, it was sure to be a hard act to follow on territory which, in many cases, hadn’t seen any motorised activity before, (remember, this was 83 years ago!).

The world’s toughest one day trial was to be based in Carlton-in-Cleveland under the jurisdiction of clerk of the course Jack Gash who must have wondered what he’d let himself in for when a massive storm arrived on the Friday and rendered much of the planned course impassable.

As the various officials sought shelter in an Osmotherley hostelry, the question was asked of Mr Gash as to how much of the course would be lost in the deluge? “Not an inch of it, it’s got to be done,” came the curt and comprehensive reply. And he was true to his word.

Luckily, the storm blew itself out overnight, so, on Saturday, November 19, 1938, 80 entrants converged on the start in trepidation of what lay ahead. Well, that was apart from a few local competitors who’d taken the opportunity during the preceding week to have a walk around the suspected route to fill them with even more dread.

One in particular was F.M. Rist of the Tanks Corps who was a professional rider in the Army. Fred to all that knew him, was a local rider from nearby Stokesley and made his name both pre and post-war in competitive motorcycling of all disciplines. So serious was he about making a good impression now the Scott Trial was to be held in his back yard, he took a whole week’s leave to foot-slog over the moors in a bid to suss out the probable course. At about 20 miles a lap, that took some doing.

With bright sunshine greeting the riders, they were flagged off from a farmhouse in Carlton and headed through uncharted territory. As these magnificent men on their fledgling machines negotiated the natural obstacles, one such section was to ride down a steep descent down into Scugdale Beck, traverse the swollen stream, and exit up a muddy slope the other side. A vast crowd had gathered to witness the spectacle which didn’t disappoint as many competitors took an unscheduled dousing in the cold water.

Onwards they battled with names such as local aces E.G. Pipe, A.W Armstrong, T Whitton, and J.H. Wood to the fore before the big guns started to show their colours. Allan Jefferies, whose son Nick, and grandson David went on to become major TT stars, survived the treacherous Ryan’s Folly section. So too did Fred Rist and the fancied Vic Brittain behind early pace-setter Len Heath.

The course skirted Sheepwash, the Drover’s Road and Chequers public house before arriving at Black Hambleton where competitors had to cross the road and view civilisation (people!) for the first time since they set off. A steep climb up the hill and then back down it saw Heath continue to head the field through sections such as Cringle Wood and Carlton Bank to end lap one.

Such was the going that only half the field survived that first lap and with darkness rapidly approaching, the ghostly moors were deemed to dangerous for them to continue. One poor rider, A.T. Johnson, broke his ankle and had to be carried a mile over moorland on a farmer’s gate to receive assistance.

The retirements continued as Vic Brittain went out with an injured foot and other tales of woe included bikes held together with billy band and a certain K.D. Haynes attempting to ride with snapped handlebars. He didn’t succeed and was left on the exposed hills until 9pm at night before he was found.

At 3.30pm, some three hours, 28 minutes, and 44 seconds after he started, Len Heath averaged 14.37mph on his 497cc Ariel to set Standard Time and with 48 marks lost on observation, he landed the coveted Alfred A Scott Trophy, 12 marks ahead of J.H. Wood. Fred Rist was third as just seven riders were initially classified as finishers, although the timekeepers allowed an extra half hour which encompassed another 13.

At the Middlesbrough Motor Club clubhouse, Councillor Swales presided over the awards ceremony where a decent sum was raised for the St Dunstan’s charity. Heath cut the 21st birthday cake which he was presented with and made sure the organising clubs got a big slice as they had overseen the transition of the event to its new home and made it a resounding success in the process, despite the weather.

Sadly, it was another eight years before the wheels of competition would again turn due to the onset of hostilities which Mr Chamberlain had promised wouldn’t happen, but the Scott Trial re-emerged in the Cleveland Hills in 1946 and stayed there until 1950.

Perhaps there’s a lesson there that despite the dark times which come along, things will eventually bounce back, and life will return to some sort of normality. Some tenuous comparisons with this pandemic I guess, but at least we are not sending our troops off to war.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here