JUST above water level on the south bank of the River Swale is a fabulous footpath made of huge grey slabs of stone, flat and stable and easily walkable.

Except in places, the roaring river has summoned up the power to suck the huge slabs of chert out of position and, in alliance with the creeping roots of trees, it has thrown the walkway into confusion.

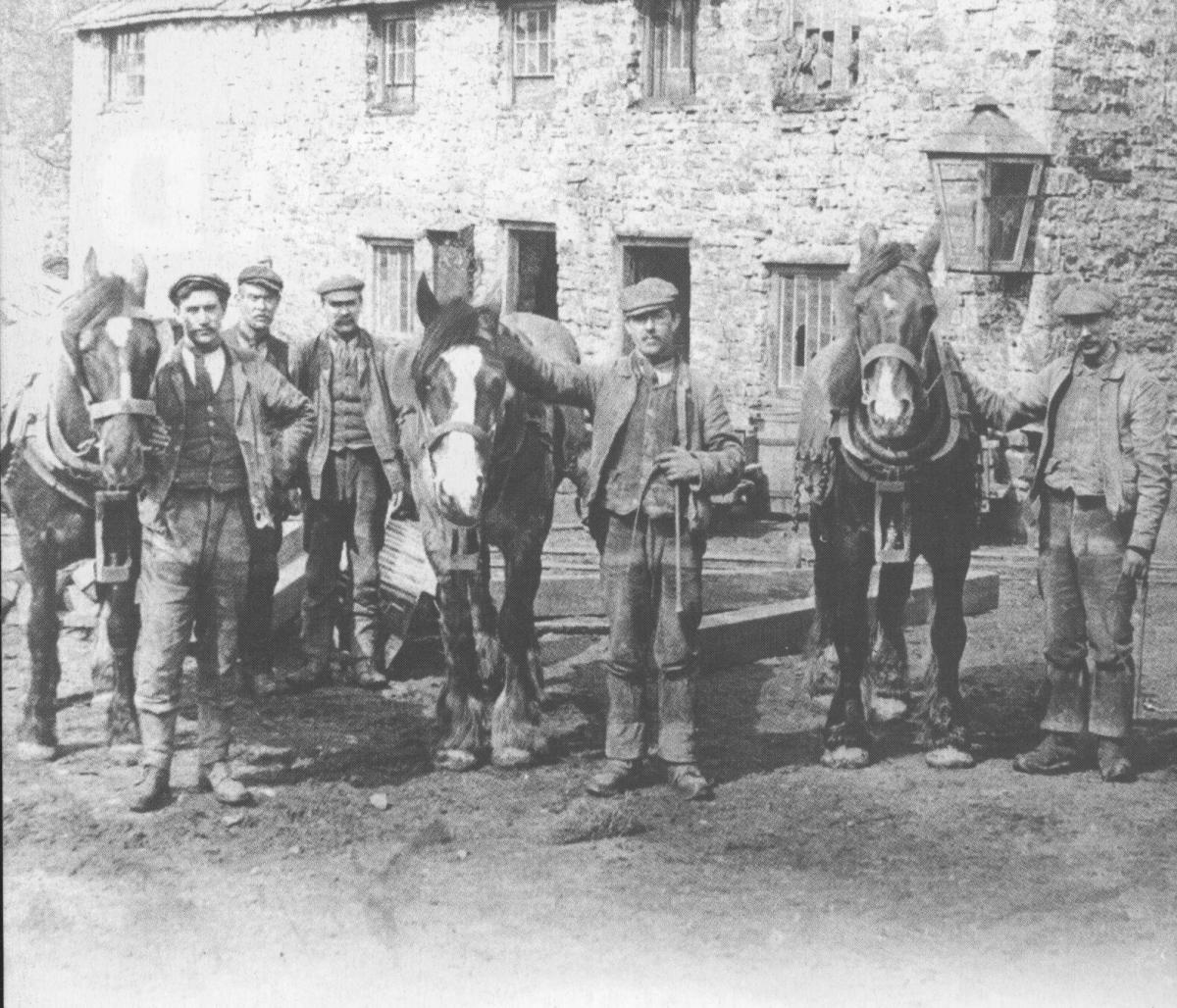

But it is more than just a walkway. It is more exotic than that. It is the remains of a causeway. Once rails were set upon it for a tramway which ran around the riverside from a copper mine. Tubs of copper ore were pushed along it until they reached Green Bridge where ponies took over and pulled the ore to the station.

Richmondians have known for centuries about the existence of a vein of copper in Billy Bank Wood which has been exposed by the Swale, and they have regularly tried to dig it out, but without much commercial success.

A copper mine at Richmond is first mentioned in a charter signed by Edward IV in 1454. In the 18th Century, inspired by the success of the copper mines at Middleton Tyas which have left such a higgledy-piggledy landscape around the village church, the Yorke and Chaytor families tried to make a go of the Billy Bank mine, but the small scale production ground to a halt towards the end of the 19th Century.

The copper tramway running at the foot of Billy Bank Wood just above the Swale in Richmond

In 1895, a new stone was sought: chert. Chert is a hard, grey flint-like material that was needed by the potteries of Staffordshire to make porcelain. With Swaledale’s lead mining having ended, many former miners went looking hopefully for chert in the Arkengarthdale and Reeth areas, and then turned their attention to Billy Bank.

A couple of Staffordshire prospectors, WS Taylor and JS Wagstaff, began mining in the steep bank opposite the Culloden Tower, and although they found some chert, the prospect of copper was more enticing. A new company was formed to once more dig into the riverbank and a monumental effort must have been made to lay the massive grey slabs of chert to create the causeway so that the ore could be carted away.

It was, though, as history predicted, a short-lived mine. There was only about four per cent copper in the stone, and the vein was only a couple of feet thick. Plus, every time the river rose, the causeway was flooded and often washed away.

Copper-mining finished in 1912. In the preceding seven years, the handful of miners had dug out 92 tons of ore worth £3,019.

They left behind the topsy-turvy causeway, and underground they left a network of tunnels which have entranced generations of moldywarps – people who enjoy traversing dark, claustrophobic spaces.

The copper tramway's run, on the right, up to Green Bridge in Richmond with the castle in the background

A fortnight ago, we told of the new book, Swaledale: Above & Beneath by speleologist Peter Ryder, with illustrations by Cluff. The caving interests of these intrepid explorers was awakened in their schoolboy days by the Richmond copper mine which was an easy walk-in off the tramway.

Over the years, their investigations mapped 4,030ft of tunnels (1,228 metres, so nearly a mile) beneath Billy Bank.

Robin Rutherford of Darlington is another whose interest in the underground was awakened by the Richmond copper mine.

“The entrance is now securely gated and locked but 30 years ago access was much easier,” he says. “We saw the old tallow candles still sitting in their mud placements on the side of the walls with the telltale smoke marks. Remains of clay pipe stubs discarded in the mud and clog marks were still discernible in some places.

Underground in the Ballroom Flat - a mined cavern so vast that in 1901 a dinner party was held down there

“When Charles and Di got married in 1981, some wag took down a complete set of a dining table, chairs, candelabra, and two place settings with photos of the lucky couple. They might still be down there now, for all I know.”

Robin Rutherford descends into the mines of the past

Robin graduated from the Richmond mine to explore the remains at Nenthead, near Alston, where the London Lead Company, based in Middleton-in-Teesdale, had one of the largest lead mines in the country. This included the famous Brewery Shaft, which today is a scheduled ancient monument. The shaft is 100 metres deep and contains pipes down which fell water from a reservoir above to help create compressed air which drove the mining machinery. Much of the waste water found its way to the Nent Force Level – an underground canal five miles long on which boats could sail.

“The trip in and out is quite epic as the only way in is by abseiling down the shaft and then prusiking out,” says Robin. Prusiking is climbing a rope through make loops for footholds in it (the footholds are secured with prusik knots which were invented by Dr Karl Prusik of the Austrian Mountaineering Club).

“My picture of the large group is in an area called the Ballroom Flat, which is a huge, rectangular chamber creating by mining. It gets its name because the lead company held a party there one year. They ferried all the guests and equipment in on the rail line, but now it is a muddy crawl and stoop most of the way. You can still find the odd chicken bone on the floor if you look closely enough.”

This must be the famous dinner party for 28 guests held by the local Masonic branch in the Ballroom Flat on September 2, 1901.

“Moving beyond the ballroom, you start dropping down through various levels and in one we came across a chamber with some wooden boxes which still contained the remains of gelignite and fuse wire. There was even an old black powder tin still sitting there – all very dangerous stuff as old gelignite is very unstable.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here