Malcolm Goodman is on the lookout for two new homes, he tells Jenny Needham – one for himself and one for his incredible kite collection

ALMOST everyone, at some time in their lives, has found enjoyment in the simple pleasure of flying a kite. Most still regard them as a child’s toy, but their history throws up some fascinating facts.

They've been in existence for nearly 3,000 years; people were flying kites, probably made from leaves, a thousand years before paper was even invented. Over the centuries they've been used for religious and ceremonial occasions, fishing, life-saving, pulling vehicles and even scientific experiments. It was also the kite which led to the development of one of mankind's greatest inventions – the aeroplane.

In wars and battles they've been employed for signalling, lifting observers, target practice, as barrage kites and for dropping propaganda leaflets. During the Cold War they were banned in East Germany because of the fear they could lift an escapee over the Berlin Wall.

One man caught up in a fascination for kites is Malcolm Goodman. It's fair to say they've taken over his life – and a sizeable portion of his home. He now has well over 1,000 kites – most beautiful works of art – and has visited more than 50 countries in pursuit of his passion.

Malcolm is cagey when it comes to saying how much he's spent on kites over the years. "As I warn visitors to my website... kite flying can be contagious and can seriously affect your bank balance!" He also refuses to divulge how much the most expensive kite in his collection, a Japanese Baromon, cost him. "A lot – it was four figures. And no, I would never sell it!"

He would, however, like to find a new home for his collection. He's 77, and he and his wife Jeanette would like to downsize from their home, a Georgian former coaching inn in Middleton-in-Teesdale, which currently houses their private Kite Museum.

Malcolm Goodman

"I've already had interest from Italy, Denmark, Switzerland and Thailand, but I would really would like the collection to stay in the UK," says Malcolm. "It's quite unique. It couldn't be reproduced or collected now as kite making is a dying art. I realised years ago, when I visited the Far East, that most of the Kite Masters in both Japan and China were getting old and had no apprentices to carry on the traditional skills. That’s when I decided to start collecting oriental kites, so that future generations would be able to see these beautiful works of art."

As far back as 1976, Malcolm met Tiezo Hashimoto, one of the most famous – and last professional – kite makers in Tokyo, who made a living National Treasure for his work in the traditional arts. "I visited Hashimoto and his wife in their workshop and was very honoured to be able to see them making their beautiful Edo kites. He died in 1991, aged 87, and his kites are now highly prized by collectors," he says. "Kite apprentices had to train for four to five years without pay; it took two to three years just to learn how to draw a straight line and circles with a brush correctly. It is mainly the hobbyists who make and fly the traditional kites nowadays."

The most extraordinary kite Malcolm has ever seen was in China, a 600m dragon. In his own collection, one of the largest and most comprehensive collections of Oriental kites in the world, he finds it hard to pick out a favourite. "I have many," he says, "a three-metre Japanese Baromon kite specially made for me from ripstop nylon and carbon fibre, a copy of my smaller Japanese one; then there's my latest addition, a 100m Dragon kite made in Bali and collected from there in 2019."

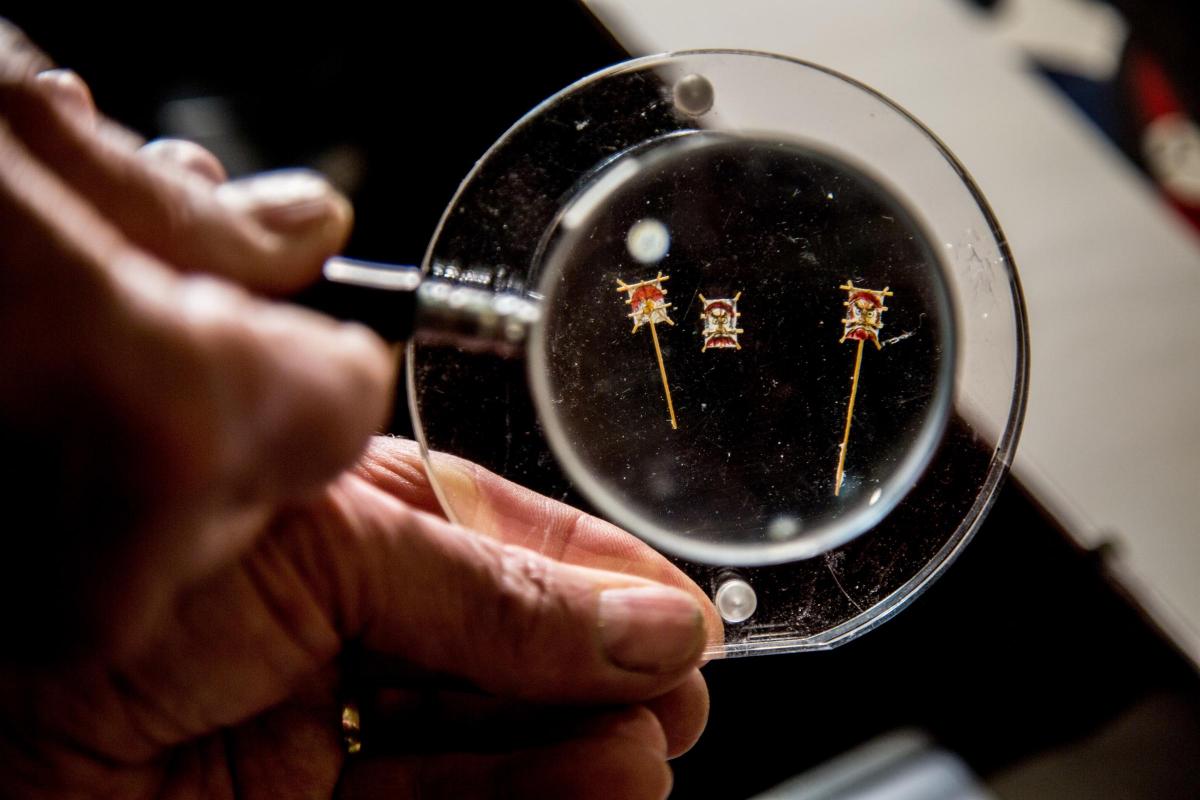

The collection also boasts spectacular three-dimensional silk butterflies and birds, exquisite five-millimetre miniature kites – retired Samurai warriors used to make very small kites from straw and tissue paper and fly them over the rising air from hot cooking stoves – to huge l00-metre dragons from China, hand-painted kites from Japan depicting warriors, priests and folk heroes, traditional snake and bird kites from Thailand, the decorative Wau Bulan (moon kites) from Malaysia, life-like birds from Bali and Vietnam, leaf kites from Indonesia, tissue paper fighter kites from India and Korea... and many more.

Malcolm, a former engineer, likes to share his knowledge with others. Nicknamed 'The Kiteman' by local children, he's been responsible for introducing many thousands of people to the joys of kite flying through displays, workshops, festivals and helping new converts to form kite clubs. In his spare time, he can be found in schools and art centres teaching the art of kite making.

Malcolm Goodman

He left school without any qualifications – he was finally diagnosed with dyslexia, aged 56 – and says his own interest in wind and flight began early in childhood. "Like many of us, I recall making and flying brown paper diamond kites with my father, but the pastime didn't grab me. In my early teens I was more interested in crystal sets and short wave radios."

Then, on a holiday to the Seattle in 1976, he spotted some adults flying single-line kites. He was so impressed he joined a kite club, mainly to receive information about kiting developments, and bought his first 'oriental' bird kite from a kite store. When he returned to England, he made a simple kite, it flew first time, and his passion took off.

"In 1981 I read in the Seattle club newsletter that they were arranging a trip to Japan to visit the Hamamatsu and Chiba kite festivals. I wrote and asked if I could join them. They said yes, so I remortgaged my house to pay for the trip," Malcolm explains. While the trip was being planned, the group was invited to China by the Peking Kite Institute, as kite flying was restarting after being banned during the Cultural Revolution. "They wanted to know and learn about western kites and the materials we used."

Over the years Malcolm and his wife have been invited to represent England at many kite festivals throughout the Far East. During their travels, they have bought, bartered and swapped kites, "and many more have been very kindly given to us". They have also invited some of the world’s best kite makers to the UK to participate in festivals and displays they've organised.

Now, while it will be a huge wrench, Malcolm is determined to find this amazing collection a new home – "in the wing of a stately home or somewhere like that, with someone who can display and take care of them".

While these beautiful and colourful creations won't be to hand any longer, Malcolm has decades of memories to cherish of chasing kites around the world – and will no doubt fly into their new home from time to time.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here