IN the grounds of Gisborough Priory there is a glorious cathedral of trees. The long limbs of the 300-year-old limes stretch heavenwards until they topple over at the top and come together, like heads bowed in prayer, to form a canopy ceiling of green.

With the sunlight flickering and filtering through the leaves, it is quite an exhilarating experience to stand, dwarfed, in the open ground beneath them.

But before you reach the lime cathedral – known as the Monk’s Walk – you pass a dark, gnarled, misshapen yew. It is practically lost in the overgrowth and it doesn’t have a name, but it could, perhaps, maybe the region’s oldest tree.

The extremely old yew in the grounds of Gisbrough Priory

Gisborough Priory – which is beside the town of Guisborough – was founded in 1119. In 1289, it was badly damaged by fire, but was rebuilt. It was during the 1290s that the splendid east window was constructed.

The priory was ravaged by marauding Scots after they had beaten the English at the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, but it recovered to become the fourth richest religious house in Yorkshire at the time of Henry VIII’s dissolution in 1539.

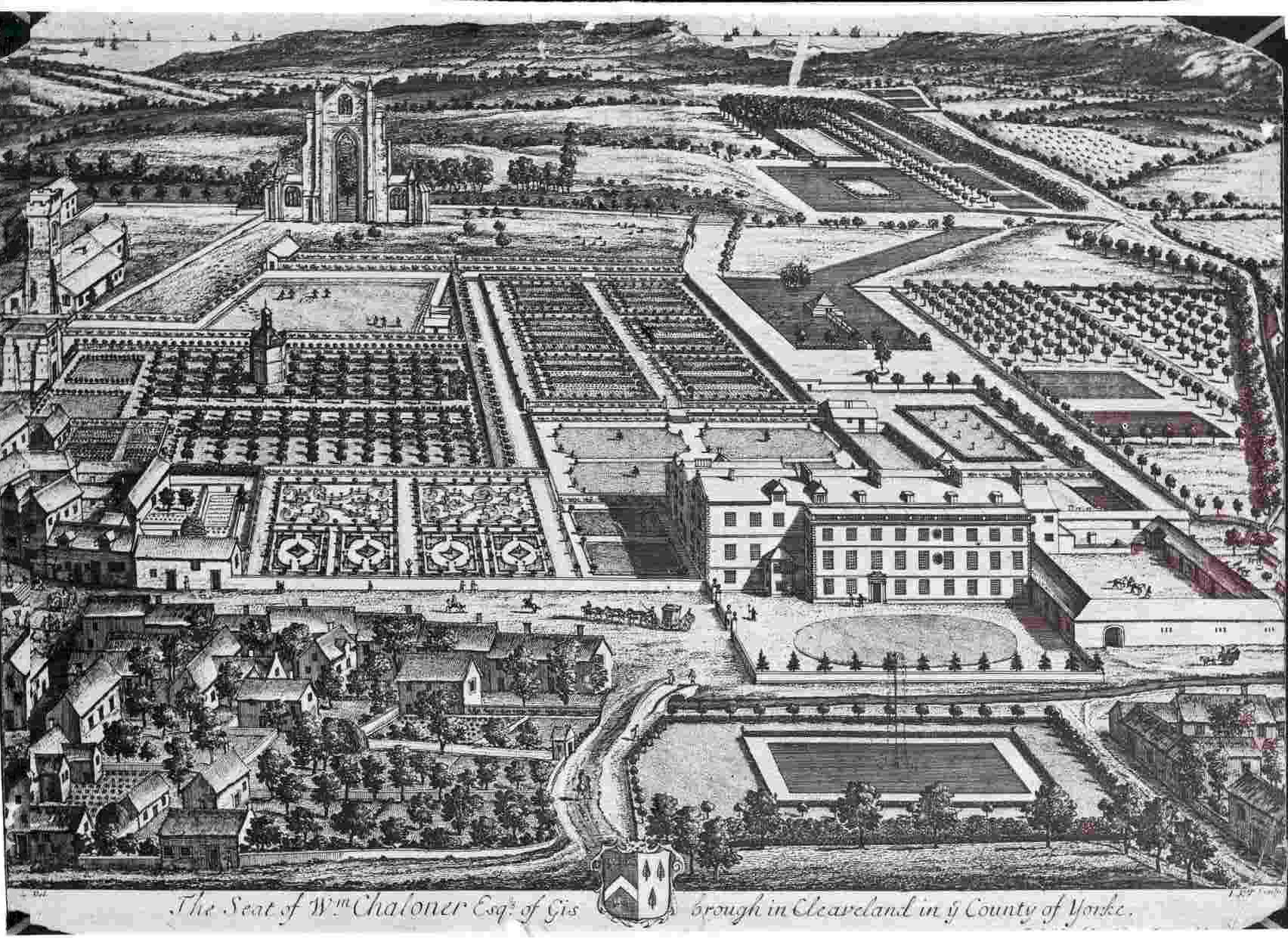

On Henry’s instruction, the priory was demolished, although the new owner of the site, Sir Thomas Chaloner, liked the east window enough to save it as a landscape feature. With the glass and stonework knocked out, it gave a splendid prospect over the family’s estate, and the family developed orchards, gardens, fishponds and a pigeonhouse in front of it.

We hailed the 14th Century dovecote at Gisbrough Priory to be the oldest still standing in this area - perhaps the yew tree could join it on our list of elderly relics

In 1680, Sir Thomas’ great-grandson, William, built the Old Hall which faced into the town but with a back garden that looked over the priory grounds towards the east window.

In the decades that followed, the Chaloners invested heavily in creating formal gardens on the priory grounds. They raised some land beside the east window and planted lime trees on it in the shape of a diamond.

It was brilliantly done, so that the view from the Old Hall looked through the length of the diamond while its widest points were exactly aligned with the east window.

The first limes were planted in the 1720s, and they were all pollarded at above headheight. It was when this fashion finished in the mid 18th Century that they were allowed to grow heavenwards.

The plan of Gisbrough Priory and gardens of 1709. Top left is the ruined east window from the priory with the parish church beside it. Bottom right is the Old Hall, which the Chaloners built in 1680 but abandoned in the 1820s when it became too wet. Now

However, by then, the Chaloners had fallen on hard times. In the 1820s, they discovered that the Old Hall had been built on a spring and had become too damp for habitation so they moved to Long Hull, a farmhouse that they rebuilt as Gisborough Hall – the current hotel.

But then, in the sudden economic downturn of 1825, Robert Challoner – the former MP for Richmond and Lord Mayor of York – became bankrupt when his bank in York collapsed. He disappeared to Ireland and never returned to Guisborough.

In the 1850s, railways unlocked the ironstone mining potential of the Guisborough area and suddenly everything was rosy once more in the Challoners’ bank account. Robert’s son, Robert, returned to Gisborough Hall and began to restore the priory gardens.

It was he who worked on the Monk’s Walk, in-planting where trees had failed so that the cathedral was complete.

All of the specimen trees in the gardens are marked on maps dating back to 1709, but it is only in 1854 that a patch appears on a plan where the scraggly old yew was growing. With its ancient limbs tumbling all over, some of them propped up to save them breaking, it clearly isn’t a specimen tree, but its multi-stemmed trunk shows that it is very old – it seems as if the map-makers, drawing the straight symmetry of their formal gardens, didn’t want acknowledge its gnarled presence until it became so old that it became noteworthy.

Gisbrough Priory with the tall trees of the Monk's Walk on the right. On its rear the picture says it was taken on June 22, 1965 (do you think this picture really was taken in late June? The groundsman, in his jacket and cap, is cutting the grass and

So how old might it be? Could it rival the Doe Park Oak, which has been growing on the cliffy bank of the River Balder near Cotherstone for about the last 800 years? Back in August we hailed as the oldest tree in the district – but could the Gisborough Yew steal its crown?

“It is a mystery yet to be solved,” says Catherine Clarke, chair of the Gisborough Priory Project, which was formed in 2007 to take on the grounds. “It is large enough to suggest that it could have been there during the time of the priory, or it is possible that it could be prior to the priory, or it could be two trees that have grown together – there’s just no evidence.”

Since its formation, the Priory Project has done wonderful work in the serene grounds, clearing the land around the Monk’s Walk so that the limes come together like the roof of a nave above the visitor’s head, and treasuring the yew.

“I would like to think it was there during the times of the priory,” says Catherine, when pressed.

If it were just a sapling when Henry VIII’s men demolished the priory, it would be 500 years old – but it could, perhaps, maybe, go back nearer to when the priory was founded in 1119, or before, which would make it very old indeed.

But, like all venerable old ladies, it is not going to be so vulgar as to reveal the precise number of years that it has withstood everything that has been thrown at it.

With thanks to Pam Rayment, and to everyone who responded to our request for information about old trees.

If you have anything to add to today's topics, please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here