From the Darlington & Stockton Times of February 13, 1869

EXTRAORDINARY scenes accompanied the funeral of the famous fox-hunter Sir Charles Slingsby, who had been one of six huntsmen to drown nine days earlier on the River Ure while in pursuit of a fox.

As we told in this space last week, nine horses had also drowned when the Newby Hall ferry – which was little more than a floating wooden platform – had capsized into the swollen river near Ripon.

Sir Charles, 45, of Scriven Park, near Knaresborough, was unmarried but wedded to his sport, known throughout North Yorkshire as the master of the York and Ainsty Hunt.

Consequently, as early as 9am on the day of the funeral, the D&S Times said that the streets of Knaresborough were already “almost impassable”. “As the forenoon advanced, train after train brought their living freight to be present at the funeral, while a continual stream of vehicles of every description brought an immense number of people from Harrogate, Leeds, Wetherby, Ripon and York and adjacent towns,” said the paper. “A monster special train from York arrived at no one, containing upwards of 1,000 of the leading citizens of Old Ebor.”

The mourners gathered in the grounds of Scriven Park which had been home to the Slingsby family since the early 13th Century, although bachelor Sir Charles was the last of the line – Scriven Park was demolished in 1954, although its stable block and gateposts remain.

“At a quarter past one the gates were thrown open, and the procession proceeded to the church,” said the D&S. “About 20 private carriages containing friends brought up the rear, which in turn were followed by a countless mass of human beings, the route, which was about one mile, being thronged with spectators, computed at upwards of 30,000.”

The inquests into the deaths had been held in the dining room of Newby Hall, which was the seat of Lady Mary Vyner. She was particularly distressed by the demise of her gardeners, Christopher Warriner, 54, and his son, James, 26, who had been manning the ferry. She had offered to defray the costs of their funeral.

The tragedy had gained such national exposure that the Times had written a leader about it. “The news of the accident has been received throughout the kingdom with as cordial a sorrow as if the catastrophe had been of universal public concern,” it said. “We hope the country will never be slow to contribute its share to the regrets which friends and neighbours manifest at the loss of such manly and kindly qualities as Yorkshire testifies to having found in Sir Charles Slingsby and his companions.”

LAST May in this column, we told how “a person named Sayer Spedding”, who was a brewer from Gilling, near Richmond, had eloped with Mary Ann Wilson, the wife of John Wilson, a groom at the Spa Hotel, Croft-on-Tees.

“The artful seducer”, as the D&S termed him, had also taken linen and half-a-dozen silver spoons. The illicit couple had been arrested in Manchester, where they were living as man and wife, complete with the spoons.

The D&S of 150 years ago this week reported on the divorce proceedings which followed the settlement of the theft charge. “The learned counsel, amid much laughter, said ‘the criminal law having dealt with the co-respondent for taking away the property, your lordship will deal with him for the carrying off of the wife’,” said the paper.

The Wilsons had been married happily for six years until Mr Spedding came to lodge with them at the end of 1867, and he had ran off with Mrs Wilson after four months.

The judge in Northallerton granted a decree nisi.

NOT everyone from Gilling was a rotter, though. “Approaching marriage of Miss Shaw of Gilling” was another headline 150 years ago this week, which led to the D&S explaining how, in 1856, Miss Shaw had been one of 16 candidates sent over to Paris by Queen Victoria for Empress Eugenie of France to choose one to be the head nurse of her only son, Louis-Napoleon.

Miss Shaw was selected.

“She has, during the 13 years which have elapsed since proved fully worthy of the trust placed in her by the Imperial parents,” said the D&S.

Miss Shaw lived in the Tuileries palace, and was a firm favourite of the heir apparent. “The Prince Imperial is warmly attached to his faithful nurse, and during a severe attack of scarlatina, from which she suffered two years ago, manifested a strong affection for her,” said the D&S.

Now Miss Shaw was to marry Captaine M Thierry of the Imperial Guard and the treasurer of the emperor’s private charities.

“The future bride is as fair a specimen of the Saxons of Yorkshire as could be found, and the respect and goodwill she has won in a foreign palace does credit to her north country origin,” concluded the D&S. “She is a native of Gilling, near Richmond, where her respected father still resides.”

WHEN Ethel Bannister was married in January 1919, her marriage certificate said she was an “experimental engineer”, which was a remarkable job title for a woman of her era.

She had had an impressive war: she’d been born in Balk, near Thirsk, in 1893, had grown up in Easingwold and had started work at Rowntree’s chocolate factory in York, but had moved into munitions manufacture.

In later life, she said she had been able to “make the perfect shell”, and she rose quickly through the ranks to become one of the HM Inspectors of Munitions.

Peace time obviously ended her munitions work, but as an “experimental engineer” in early 1919, she was still pursuing an untypical line of work.

All that ended in December 1919, when she gave birth to the first of her eight children and her career came to an end. Before she left the munition works, though, she had taken a funnel which had been used to put munitions into shell casings. It was later turned into a stand to hold a fire poker as a souvenir of her war work and is still treasured by one of her grandchildren in Middlesbrough.

The story, and the poker stand, were unearthed during roadshows held late last year by the Rememorial WW1 project, which is looking at how the Tees Valley coped in the period from the signing of the Armistice on November 11, 1918, to the final conclusion of the peace with the Treaty of Versailles on June 28, 1919, and Peace Day on July 19, 1919.

“It was a period of considerable uncertainty as people tried to come to terms with peace,” says Dr Ben Roberts of Teesside University, who is leading the Heritage Lottery funded project. “Society itself was adjusting in the wake of total war and this change brought mixed experiences of hope, anger, joy and sorrow.”

The project is building into an exhibition which will tour the region’s museums to commemorate the centenary of the peace later this summer.

Dr Roberts and his team would like to hear from anyone who has similar stories about this period of immense upheaval. They can be contacted by email, info@RememorialWWI.org, or phone on 01642-738538, or RememorialWW1 can be found on Twitter.

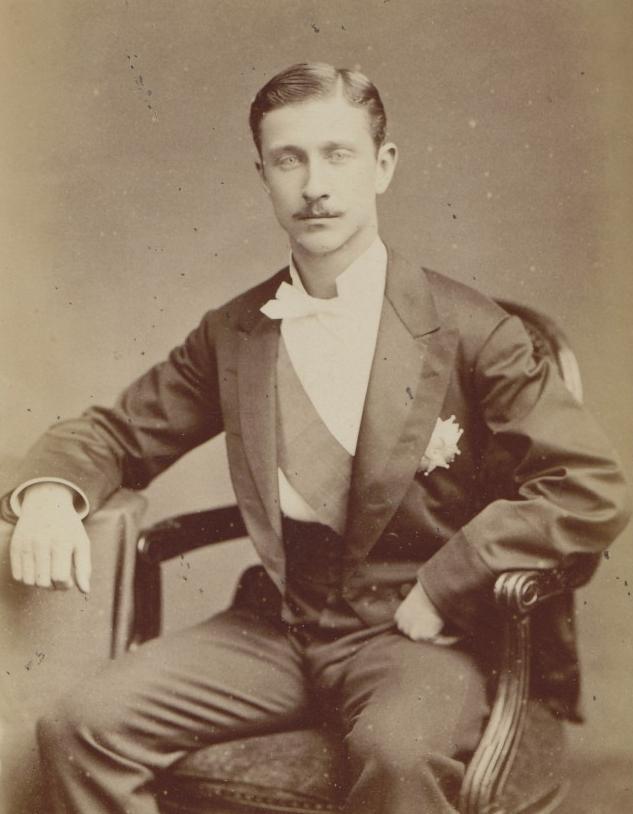

IN recent weeks, we’ve been following the story of Lord Ernest Vane Tempest of Wynyard Hall whose “strephonic tendencies” were his undoing.

Lord Ernest was the son of the 3rd Marquess of Londonderry, who was twice drummed out of the army for misdemeanours involving an actress and a shaven new recruit, and who stood unsuccessfully for the Conservatives in Stockton in 1868.

But he is not the only one with such tendencies in the Vane Tempest family tree, and we are grateful to Chris Wimshurst for pointing us in the direction of the wife of the 9th Marquess of Londonderry.

She was Nicolette Harrison, born 1940, the daughter of a wealthy London stockbroker and a Latvian baroness. She was one of the last debutantes to be presented to the Queen and by the time she was 16, she was engaged to the 9th Marquess, 20, who had inherited the Wynyard estate two years earlier when his father, the 8th Marquess, succumbed to alcoholism.

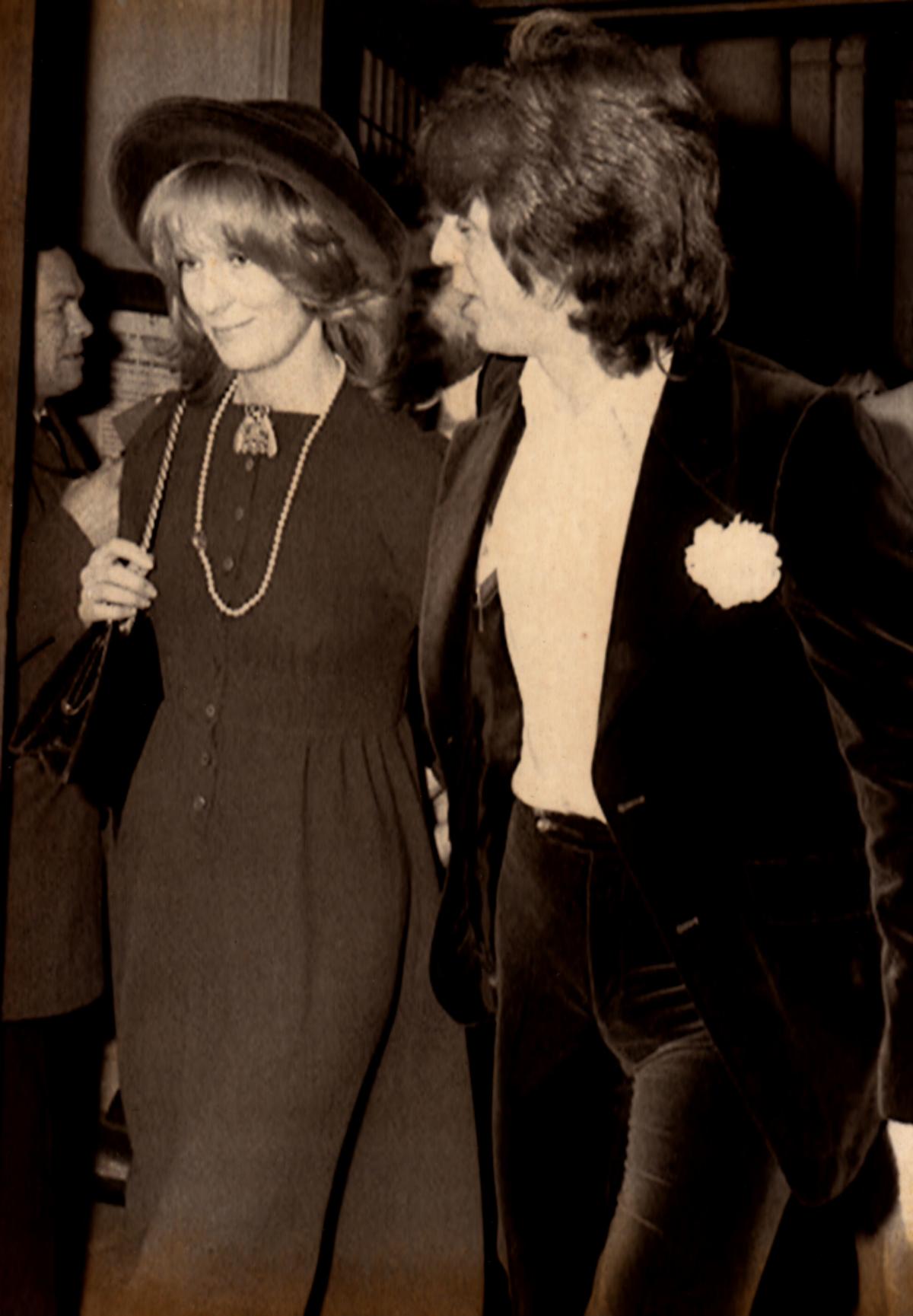

Nico and the marquess, who lavished a fortune on restoring Wynyard, had two children, but then in early 1965, the marquess’ sister, socialite Lady Annabel phoned her up and told her to have a look at Top of the Pops on the telly – a cute, 22-year-old singer called George Fame had his first hit at No 1, Yeh, Yeh.

Yeah, yeah, thought Nico, who was smitten.

It is said that when Georgie played at The Globe in Stockton on April 2, 1965, she made it into his dressing room; that went so well that when he played the Redcar Jazz Festival on October 31, 1965, photographers were kept well away as the pop star was being accompanied by “a real cool chick with a handle”.

In 1969, Nico gave birth to her third child, Lord Castlereagh. Her suspicious husband confronted her, a blood test was performed, and Fame was identified as the father.

The divorce in 1971 was a front-page sensation, particularly as the ex-marchioness immediately married her pop star in front of the world’s cameras at Marylebone Register Office.

But just as Lord Ernest’s story of strephonic excesses didn’t end happily, nor did Nico’s. She took her own life in 1993 by jumping off the Clifton suspension bridge near Bristol. She left a note saying she had "no purpose in life" once her children had left home.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here