THE fading of time leaves some stories of war rather hazy. The blood and the bullets of Pte Thomas Jackson’s war are now just a plastic folder of tatty pictures, yellowed newspaper cuttings, some silk postcards from the front, a pencil-written diary from 1917, and some hazily remembered anecdotes passed uncertainly down the generations.

But it was a four-year war of great vibrancy and bravery, fought in two theatres thousands of miles apart, and although Thomas survived, his exploits contributed to his premature death.

Let’s start with the few known facts. Thomas Robert Jackson was born in Evenwood in 1885, the second of seven children. He was a miner, and on June 30, 1909, he married Phyllis Ann, of Temperance Terrace, which is an isolated row of mining houses midway between Crook and Billy Row. They set up home in No 24, Temperance Terrace, which was where their daughter, Ethel, was born on September 16, 1910.

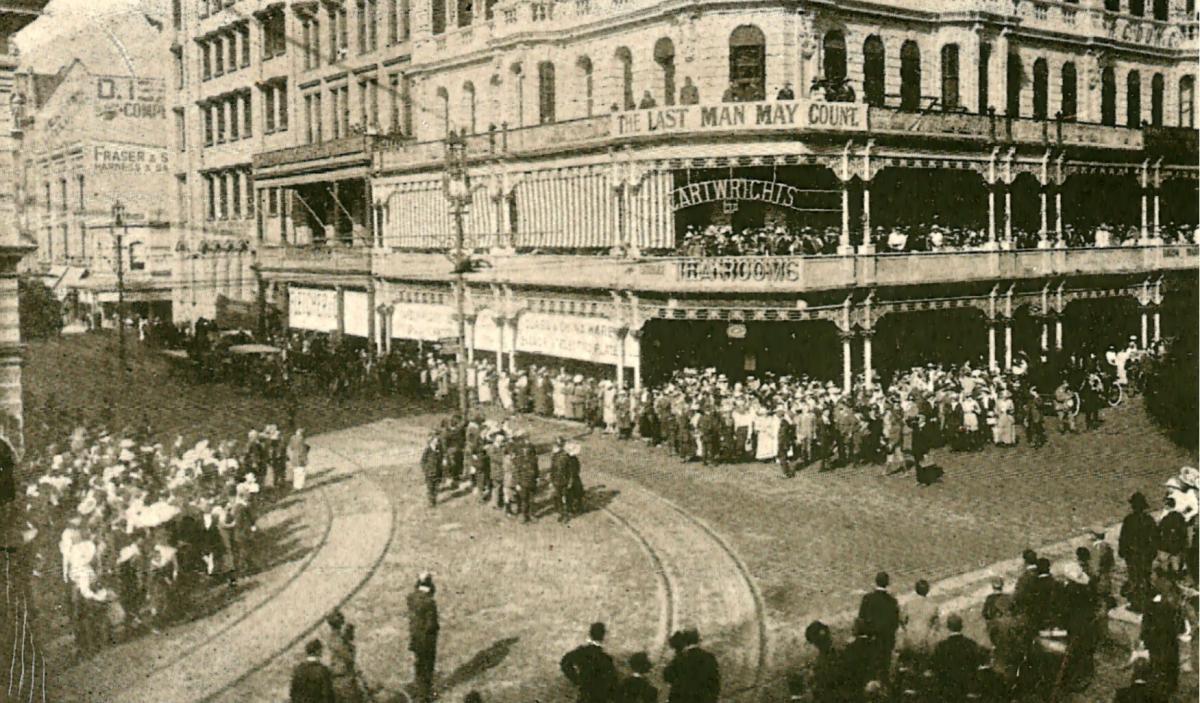

In 1914, Tom joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, and seems to have been posted, probably with his brother, to Blackpool, where the RAMC had a training headquarters, teaching men how to run the battlefield medical services.

When a soldier was injured on the frontline, he was picked up by the Field Ambulance – not a vehicle, but a team of stretcher-bearers which conveyed him to the Dressing Station, where basic first aid was performed. Those casualties requiring more assistance were sent, by Field Ambulance or a horsedrawn carriage, a couple of miles behind the frontline to the Casualty Clearance Stations (CCS) where rudimentary medical treatment was given.

It is no coincidence that where CCS were established during the First World War are today war cemeteries.

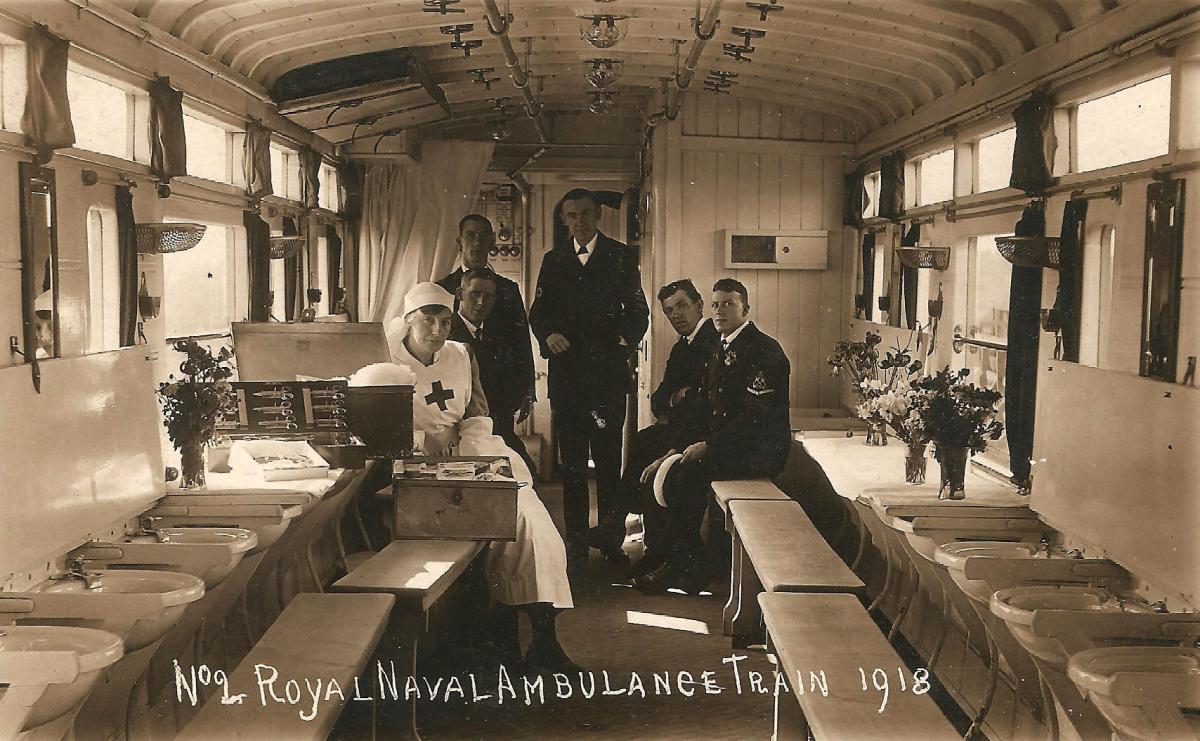

Those fortunate to survive the CCS were evacuated to a Base Hospital, in northern France, or a home hospital in Britain, usually by train.

In 1916, the RAMC evacuated 734,000 casualties from the CCS to hospitals on its 28 ambulance trains.

Tom was in the thick of the action. We know this because the folder contains seven silk postcards that he sent home to Temperance Terrace. The cards were handmade in France and were sold to the soldiers by the villagers in whose fields they were fighting.

The villagers often wove regimental badges into the cards so that they appealed to the soldiers who were could be in their area for only a few weeks. So Thomas has sent home a “RAMC 1915” card to Phyllis as well as a couple of more generic cards dedicated “to my dear wife”.

They have little pencil messages on the back: “With best love and good wishes. I hope you like this card. From Tom”. His name is always followed by an explosion of kisses.

There’s one card dedicated “to my dear child”. It was more expensive than the others as it has a silken pocked on the front in which Tom put an additional little card which he had bought for another cent or two.

It must have been worth the expense, though, as it marked a special occasion. “For my little pet, wishing you many happy returns of your Birthday,” he wrote on it in pencil. “Hoping you are in the best of health. From Daddy.” He finishes it, of course, with an explosion of kisses.

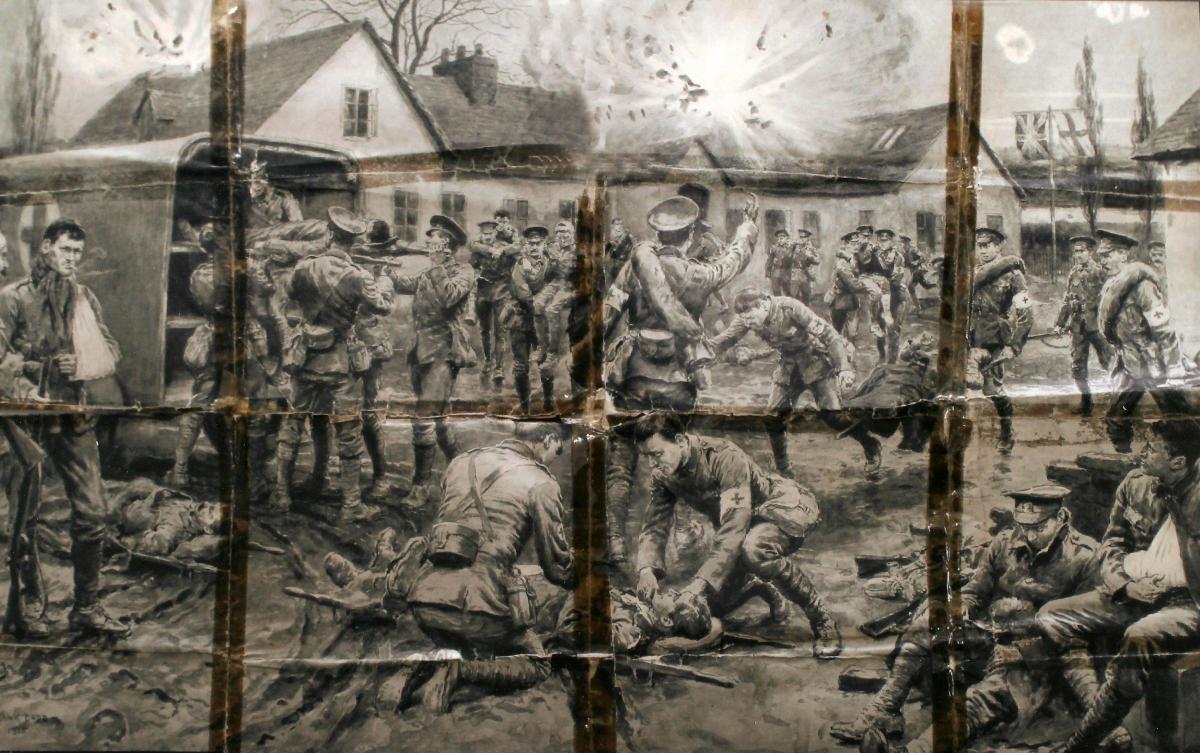

What was Tom’s role on the frontline? All we have is a hazily-remembered story and a yellowing page torn from a contemporary illustrated magazine. The page has been folded many times, and over the decades each crease has been strengthened with a line of see-through sticky tape.

But, over the years, the tape has long since lost its stickiness and peeled off, leaving a discoloured tramline.

As the page is unfolded it reveals a dramatic drawing of khaki-clad men carrying their wounded as a shell explodes overhead, the artist portraying its enormous starblast like the rays of the sun on a misty day.

The artist is Frank Dadd, who produced frontline scenes for publications like the Illustrated London News, often from the safety of a desk. This one is dated 1915 and it is entitled “The work of the RAMC: evacuating a dressing station under heavy shell-fire”. The caption says it was drawn “from a description by an officer who was present at the engagement”.

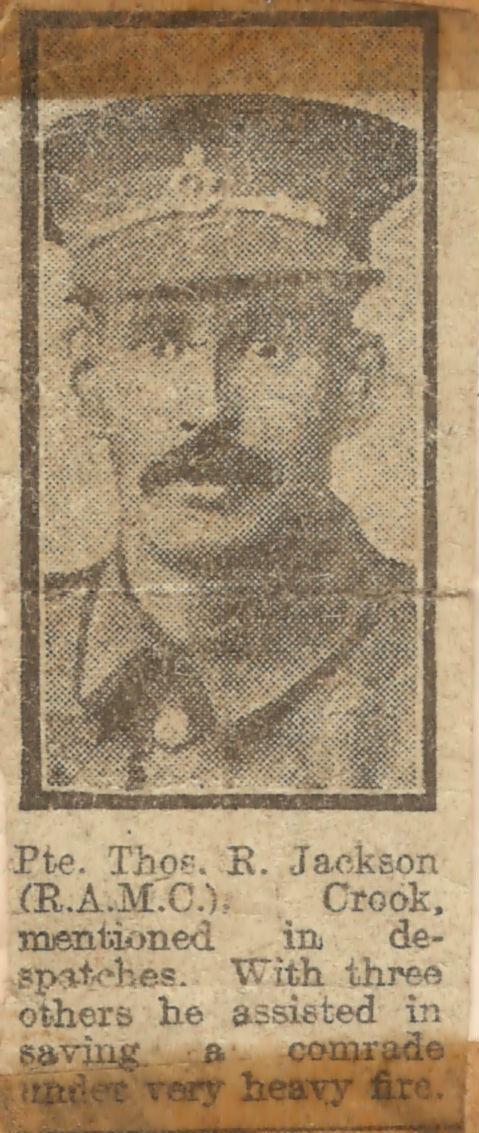

Sellotaped to a corner of the page is a clipping, perhaps from The Northern Echo. It shows a picture of a heavily-moustached Tom in his RAMC cap with a sentence underneath: “Pte Thos R Jackson, Crook, Mentioned in Despatches – with three others he assisted in saving a comrade under very heavy fire.”

The hazily-remembered story is that on Dadd’s drawing, among the walking wounded with their arms in their slings and the stretchercases being loaded, like finished trays in a self-service restaurant, onto a multi-storey rack in an ambulance, the heavily-moustached Tommy in the RAMC cap giving a piggyback to an injured comrade is our man Tom.

Between 1914 and 1920, 141,082 men were listed in the London Gazette as having been Mentioned in Despatches – they must have done something outstanding for their senior officer, in writing up the day’s events, to have noted them individually – and Tom would have been able to wear an oak leaf badge on the ribbon of his Victory Medal to signify his mention.

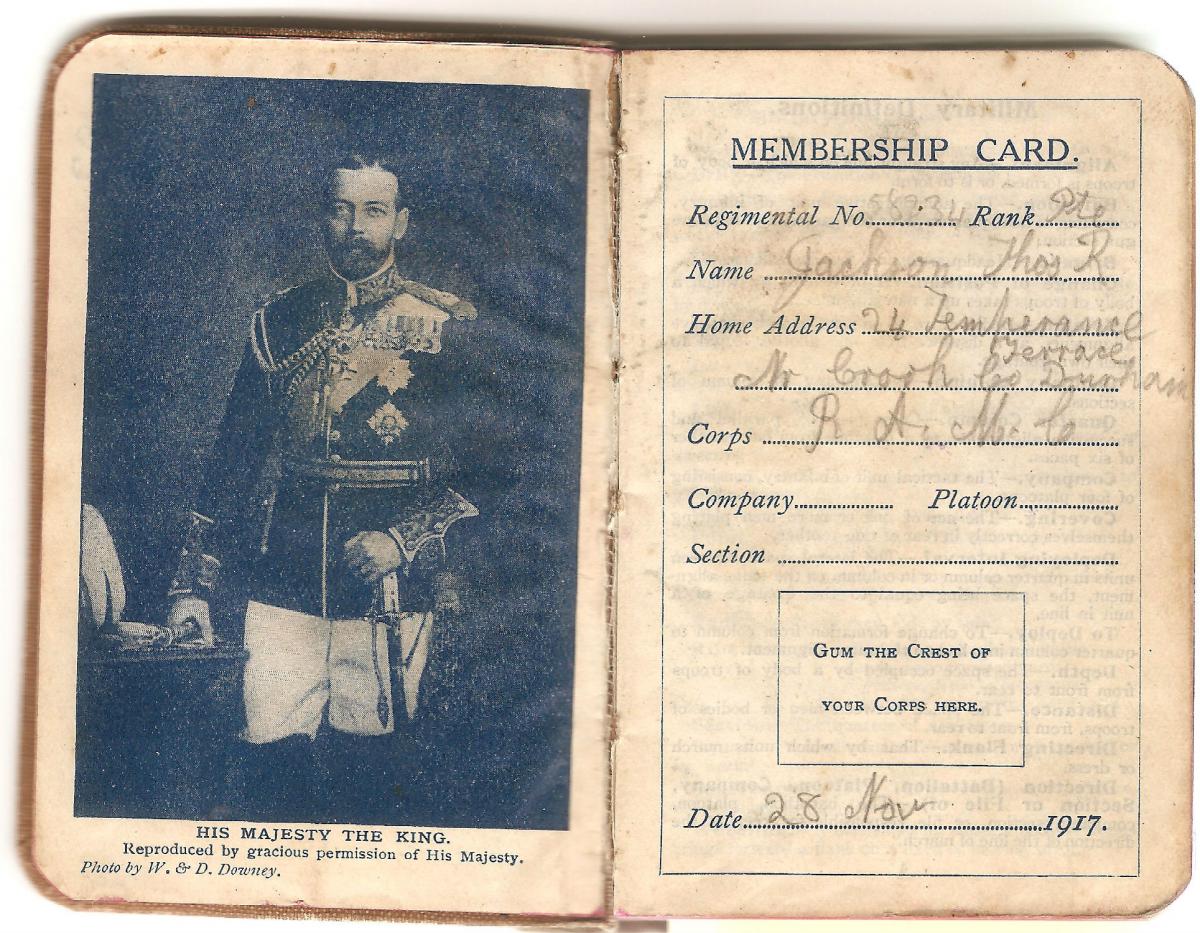

Where the war immediately took Tom after northern France in 1915 is not known. We next pick him up when he begins filling in a credit-card sized booklet, The Soldier’s Own Diary, on November 26, 1917.

The hessian-covered diary is packed full of useful, soldiery information – what the identification flag of a veterinary hospital looks like, parts of a rifle, a table showing how far a rifle bullet will penetrate different materials, useful knots, how to find your direction at night, and a dictionary of soldiers’ vocabulary where “chucking a dummy” is defined as meaning “to faint on parade”.

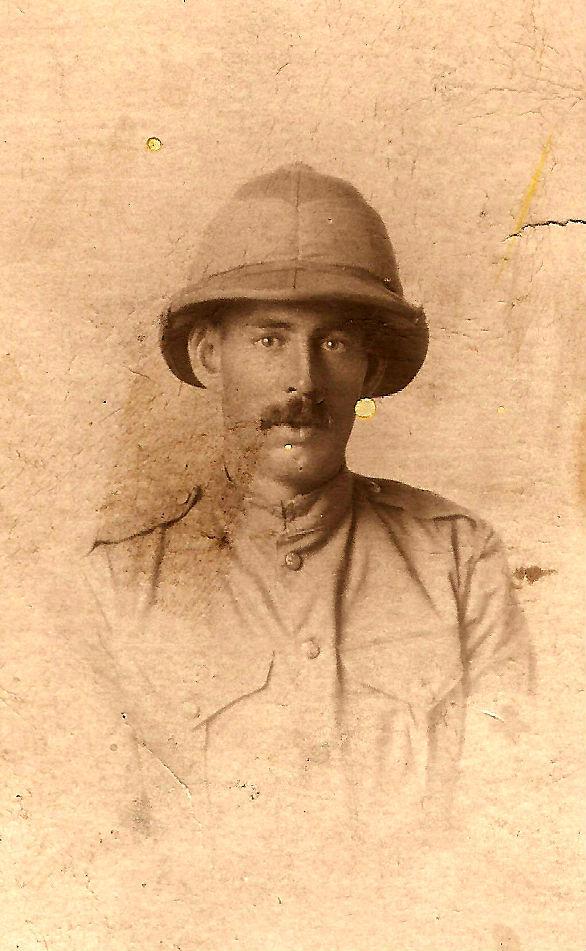

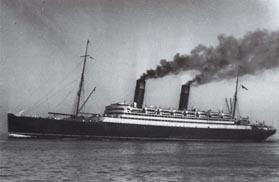

Tom, though, is on an exciting journey. In spidery, pencil writing, he records how he left Blackpool on the SS Medic, an Australian liner requisitioned as a troopship, and is bound for German East Africa.

Today, this is a little regarded theatre of war, but it covered a huge area of what we today know as Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. The British deployed about 250,000 troops and 600,000 conscripted Africans – known as “carriers” as they did all the donkey work – in chasing a German force of about 20,000 soldiers assisted by about 10,000 “carriers” around the desert. A little more than 11,000 British troops were killed along with about 95,000 carriers as disease took its toll more readily than the bullets.

Three days into his voyage, Thomas wrote: “A lot of the lads were very sick but it did not affect me at all. Started to play house at night.”

It must have been a tense voyage. The Medic was part of a convoy with an escort of eight destroyers and a cruiser, and as they sailed in European waters, they were shadowed by the deadly threat of U-boats.

“Was compelled to wear our lifebelts all day,” Thomas wrote on November 30. “Played cards at night.”

They reached Sierra Leone on December 13 – “the natives came round the ship selling fruit and diving for pennys” – and set sail two days later, expecting to reach Cape Town in South Africa on Christmas Day.

“Still at sea,” wrote Tom on December 25. “Got some nuts and an apple. Lost ten pounds last night.”

They landed at 3.30pm on Boxing Day. “Had a fine time in Cape Town till eleven o’clock,” he wrote the following day. “It was amusing to see so many black women about.”

After a day or so on dry land, they were off, rounding the notorious southern tip of Africa – “ran into a heavy storm,” wrote Tom on December 29. “It was a beautiful sight when the lightning flashed” – before reaching Durban on New Year’s Eve, where they were treated to a tea, a concert, and visits to the races and the pictures.

Then they saw the RMS Caronia, which was supposed to take them on the final leg of their voyage to Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania. Caronia was a Cunard liner with a footnote in the most famous maritime story of all time, as she’d been the first vessel to send Titanic a warning about icebergs…

As a troopship, though, she was well past her pre-war prime.

“All the troops refused to go on the Caronia because she was so lousey and so dirty,” wrote Tom on January 4. “We marched to the camp and left the ship. Expect trouble any time now.”

Four days later (so there can’t have been much of a deep clean) and they were leaving Durban aboard Caronia for Dar es Salaam, which they reached on January 15.

“Looks a God forsaken hole,” noted Tom. The following day he wrote: “Left the ship today 12 o’clock – everything German here. You would laugh if you saw us with our nets at night.”

They were troubled by mosquitoes at night and the “red hot” temperature of the day forced them just to lie in their tents until they became acclimatised.

“Went on an island here and got some lemons, limes and pineapples and coconuts,” wrote Tom on January 24. “It rained all night in torrents. Saw Joe Snowden last night. Was pleased to see him.”

Tom volunteered to work as a nursing orderly on board SS Germanic, an old British liner that had been captured from the Turkish, who had sided with Germany, and put to work as a hospital ship. “Got put in the officers ward,” wrote Tom. “There is plenty of work but we get plenty of grub.”

However, he lasted just four days.

The entries for the week commencing February 4 are rather confused. “Had an attack of fever, got a good sweat, felt better,” he wrote. “Felt rotten all day with a bad head. Feel worse today will report sick tomorrow. Sent into dock.”

The next entry is dated February 24: “Came out of hospital today.”

Which is quickly followed by February 28: “Went into hospital again today with fever.”

Then all is quiet until March 14: “Came out of hospital again today. I wonder how long I will be out this time.”

He answers his musing with his next entry, on March 24: “Went into hospital again today.” Three days later, he wrote: “Was very ill today. Getting worse. The doctor told me it is pleurisy with effusion.”

His next entry reveals that on May 18, he left German East Africa on the hospital ship Vita – which had been built by Swan, Hunter on the Tyne in 1914. The Vita took him south to a hospital in Cape Town, where he was housed in a tent with three other patients.

He had recovered enough from his fever to send seven-year-old Ethel a booklet on June 2 which showed how every day at midday in Cape Town there was a “hush two minutes” as the whole town stopped what they were doing and “thinks of what our boys and girls are doing for us in the great world struggle”.

He records that on July 3, the hospital ship SS Marama set sail from Cape Town taking him home. He sailed north again, past German East Africa, through the Suez Canal to Port Said in Egypt and then on to Le Havre before he ended his diary in the Grove Military Hospital in Southampton on August 31, 1918.

In his diary, Tom worked out the “distance I have travelled on the water” halfway round the world from Blackpool, and then back again after just four days of service: 21,030 miles.

But at least he was home with Ethel and Phyllis in Temperance Terrace in time for the armistice celebrations – although his former comrades in German East Africa kept fighting until November 14, when a telegram came through telling them of the latest news from Europe.

The penultimate item in the plastic folder is a scratchy picture of Tom, Phyllis and Ethel that was taken at Blackpool after the war ended – there’s a drawing of the tower behind them on the wall of the photographer’s studio. It is believed they were visiting Tom’s brother, who was still with the RAMC.

On the picture, Tom is seated, with his womenfolk leaning upon him. He is in a civilian suit and tie. His hair is neatly parted, and he has a big moustache beneath his distinctive, full lower lip. His dark eyes stare intently at the camera, and there are no traces of smiles on any of the family’s faces.

The last note in the folder is in biro. It says Thomas Robert Jackson never recovered his health after the war, and he was living with Phyllis and eight-year-old Ethel in Dawson Street, Crook, when he died in 1920.

He was only 35. He had spent four years treating the wounded and the sick from northern Europe to eastern Africa, and had performed his duties with great bravery – although, judging by his losses, his card playing skills were never up to scratch. Wherever he had travelled, he had clearly kept his wife and daughter uppermost in his mind, noting at each port he docked in how he had sent them cards and letters.

But he returned to them a broken man, perhaps as that last scratchy photo shows, and he died desperately young. Although his name is not on Crook war memorial, he is as much a victim of the war as any of those who laid down their lives in uniform.

THE folder that contains the war story of Pte Thomas Jackson was lent to us several years ago by his Bishop Auckland family, but their contact details no longer work. Please email chris.lloyd@nne.co.uk if you have any information

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here