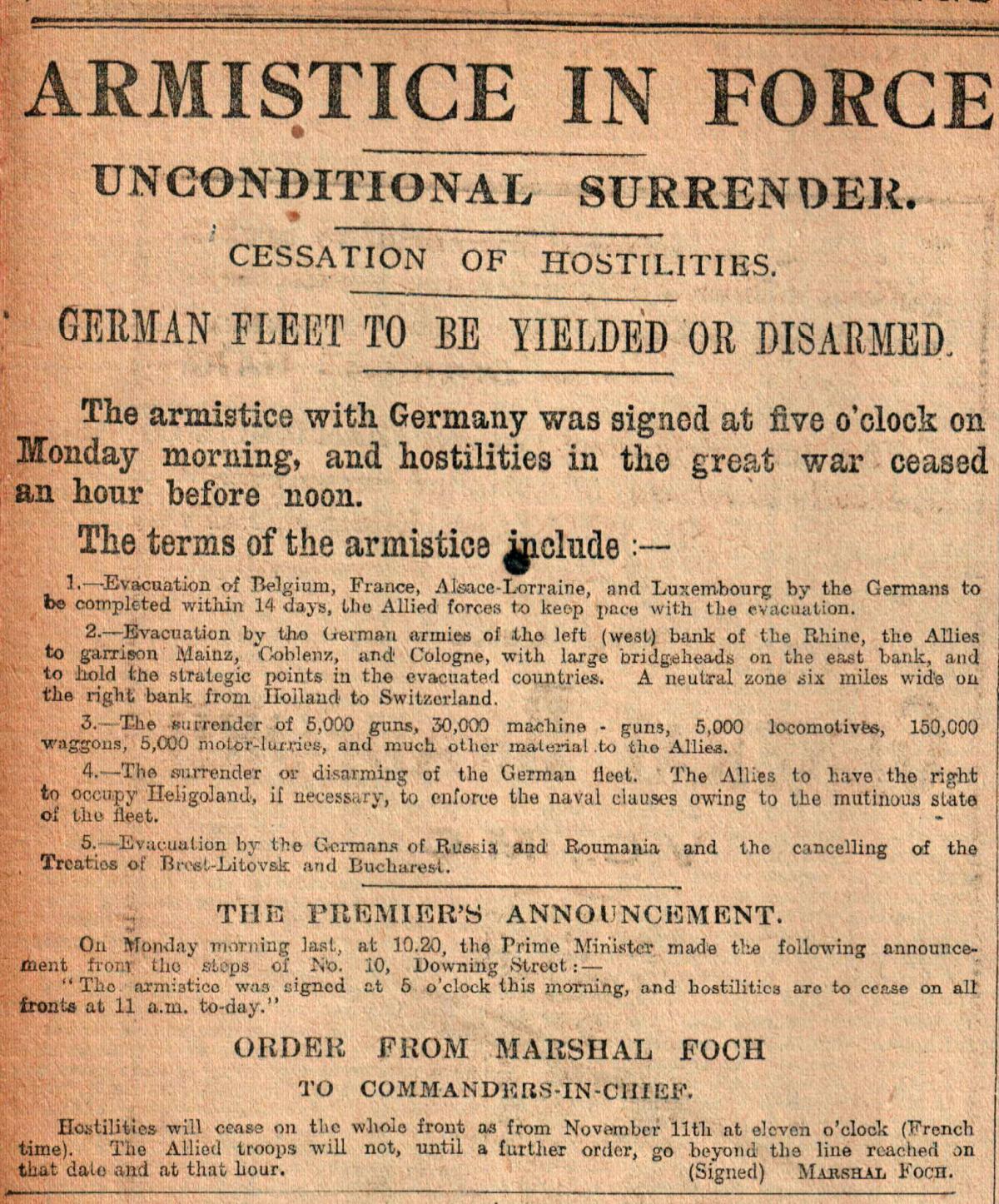

NORMALLY in this column, we look back in the Darlington & Stockton Times’ archive to the edition of exactly 100 years ago. However, bearing in mind that a newspaper can only report the news after it has happened, today we look back at the edition of November 16, 1918, to see how the area greeted the news of November 11 that, after four-and-a-half years, the war had come to an end.

The D&S said the news reached Darlington at 10.45am, and most other towns became aware of it at about 11am, but it wasn’t until 12.30pm that Middleton-in-Teesdale heard the glad tidings, and Bedale had to wait until 1pm.

There was a pattern to the way the news was received. “For the moment, the citizens of Ripon were rather inclined to be sceptical, remembering the incorrect rumours in circulation a few days earlier, but very quickly the telephone messages were authenticated,” said the D&S. Ripon wasn’t alone – most towns needed convincing the news was not fake.

Once convinced, flags and bunting appeared at a magical rate, and people downed tools and congregated in town centres. There were impromptu church services and parades by injured soldiers, and at 3pm the leading citizens of each town gathered on market steps and read the king’s proclamation of victory, after which everywhere exploded into a celebratory cacophony.

Noise, noise, noise – and, as dark drew in, light, light, light.

Noise because church bells had been banned since 1914 and so the news of victory was greeted with joyous peals plus klaxons on factories and collieries sounding and ships on rivers ringing bells.

Light because the black-out had made days very dark and so communities quickly gathered for bonfires and torchlight parades.

And fireworks, which combined both noise and light. Fireworks had been banned, and many people expressed surprise that so many shopkeepers could source so many fireworks so quickly.

The D&S reports were compiled a day or so after the events whereas the paper’s daily sister companion, The Northern Echo, was writing almost instant judgements. Whereas the D&S reports of the joy, the Echo repeatedly notes how there was jubilation without gay abandon. It says there was none of the wild boisterousness of 1900 when the news that the siege of Mafeking, in South Africa, had been greeted with such scenes of reckless celebration that a new word had entered the English language.

An Echo reporter on Teesside, using that new word, said the mood of jubilation on November 11 was tinged with profound sadness by saying: “The sister towns of Stockton and Thornaby were ablaze with bunting, but there was not the slightest evidence of mafficking.”

This is how the D&S of November 16, 1918, spoke of the joy that it found in the towns in its area:

Darlington

THE town set the pattern for the riot of noise to be found everywhere. “The glad tidings was hailed at Darlington with great delight, which found expression in the blowing of buzzers, the clanging of bells and the firing of guns,” said the D&S. “By general consent, men and women ceased work and streamed out into the streets, which were quickly gay with flags and bunting.

“Fireworks, prohibited since 1914, made their appearance from some mysterious source and were discharged by persons in the crowd, while detonators placed on the tram lines resounded through the evening air. While the enthusiasm was intense, the proceedings were happily unmarked by rowdyism.”

Ripon

A TRAINING camp had been established to the south-west of the city at the outbreak of war, and it had grown to hold 30,000 men – it is estimated that 350,000 men passed through it during the four years, and now the memorial on the turning to Studley Roger marks its site.

“Six blasts were blown on the camp buzzer,” said the D&S as the camp dissolved into “the wildest excitement”. “Bombs were exploded, Verey lights fired, and blank ammunition discharged.”

The soldiers descended on the Market Place. “There were many amusing incidents during the afternoon,” said the D&S. “A sack of potatoes was detached from a NACB lorry, and very quickly potatoes were thrown about in all directions. On another occasion the men helped themselves to a number of buns from a lorry, much to the amusement of the spectators.”

Getting smacked in the face by a flying spud would make the day memorable.

Masham

POSTMASTER T Metcalfe announced the good news at 11am, and flags sprung out on the houses and shops as the church bells rang out merrily.

“Several of the wounded soldiers from the Town Hall Red Cross Hospital obtained rifles from the Drill Hall and marched to the hospital, where from the balcony they fired several volleys,” said the D&S.

The evening ended in fireworks and bonfires on which effigies of the German Kaiser and Crown Prince were burned.

“THE wounded soldiers in blue gathered about the Market Cross and Market Place on the lookout for whatever happened in which they might participate to give expression to their intense feelings of gladness and thanksgiving,” said the D&S – convalescing soldiers wore blue uniforms.

Bedale

IN the evening, there was a bonfire in the Market Place and another effigy of the kaiser was burned.

Wensleydale

THE dale’s brass bands burst into patriotic selections, and both Hawes and Askrigg churches opened their services opened with All people that on earth do dwell.

Middleham

“FOR the first time since early in the war, the trained bellringers rang merry peals at the parish church. At night a bonfire was set alight and fireworks were let off.”

Thirsk

“THE fact was announced from the steps of the Market Clock by the Rev HPH Austen (vicar) and the Rev J Toyn (Primitive Methodist),” said the D&S. “The Doxology and National Anthem were sung and three cheers for the king were given. The town was soon beflagged, and for the rest of the day the younger section of the populace expressed their joy by an abundant fireworks display.”

Great Ayton

AT the Friends’ School, an oak sapling was planted in the playing fields. “With the tree was buried a copy of a newspaper containing a record of the signing of the armistice, coins of the realm, and the fact that the tree was planted upon that memorable day by Mrs Denniss (headmaster’s wife), assisted by Granny Nicholls who, for over 50 years, has baked the scholars’ bread,” said the D&S.

“THE Boy Scouts arranged a torchlight procession in the evening, and there were many firework displays. The York and Lancaster Regiment held a dance at the Witham Hall in the evening.”

Yarm

“IN the presence of a large crowd, a huge bonfire was set ablaze in the middle of High Street and at that moment a torchlight procession consisting of patients and nurses from the Eaglescliffe VAD hospital (the Voluntary Aid Detachment hospital which looked after convalescing soldiers), dressed in comic costumes, entered the town, conveying along with them an effigy of the Kaiser (which was afterwards burned at Eaglescliffe). Blazing tar barrels were rolled up and down the street and fireworks displayed in profusion.”

Stockton

THE D&S said: “The lighted streets were crowded to a late hour, the young element thoroughly enjoying itself with displays of fireworks and improvised bands, the like of which had not been seen or heard these many days. And now the inhabitants eagerly await the day when they can give a right royal welcome to the lads who have endured so much for England and the Empire’s sake.”

The Northern Echo noted: “Royal Irish Fusiliers band, billeted in the town, paraded into Stockton headed by its drum and fife band and chairing apparently the regimental mascot in a big dog, which by its demeanour did not appear to share in the prevailing spirit of gladness.”

THE Town Crier was sent out to make the announcement and call people to the Market Cross to hear the official proclamations.

“A holiday having been proclaimed at the adjacent military camp (at Catterick), the crowd was largely reinforced by cheering soldiers, whose strident enthusiasm over the cessation of hostilities formed one of the features of a notable assemblage,” said the D&S. “An equally pleasing feature was the host of children, who with their flags and joyous acclaims almost literally made the welkin ring.”

“The mayor congratulated those present that the greatest and most devastating war the world had ever known had now been ended, and the German militarism and all that is meant for the freedom of the world had been triumphantly shattered. (Applause).”

FOR all this great joy, there was deep sadness. The edition of the D&S that brought news of the celebrating across the region also carried a list of local casualties.

“At the close of a week of general rejoicing and thanksgiving, the sad news was received in Leeming on Tuesday that Lance-Cpl William Critchinson, 21, had been killed on November 6,” said the D&S, meaning that the Critchinsons had learned of his death the day on November 12. How must his parents, John and Minnie, and his aunt, with whom he lived at Newton Grimescar Farm, have felt, particularly as his brother Thomas, 18, had been missing since May 28 and would never make it back?

And what about Miss Simpson of Romanby, who that joyous week received a letter from a chaplain in the Royal Field Artillery stating that her fiancé, Driver W Marrison, also of Romanby, had been killed on November 2. While everyone was rejoicing , she was reading: “He was taking the guns into action, and had to pass along a road which was being heavily shelled by the enemy. Unfortunately one shell hit him and a comrade. Death must have been instantaneous.”

Driver Marrison, a Northallerton cabinet maker, had joined up in September 1914 and had made it all the way through only to fall at the very last hurdle.

The other side of the coin was that Mr and Mrs John Priestman of Newsham, near Kirby Wiske, “wish to contradict the announcement that their son, Pte Albert William Priestman, is killed. He is wounded and a prisoner of war in Germany”.

The D&S explained: “Only a fortnight ago his death was reported in these columns. An officer of this regiment wrote to his parents stating that on October 2, Pte Priestman went forward with his officers. A report was received the following morning that they had been surrounded. Attempts were made to rescue the party but it was not until a few days later that their comrades were able to reach the trench and there they found the body of Pte Priestman. From the postcard now to hand it is plain that this was a case of mistaken identity.”

What relief in the Priestman house that the war was over and that their son was alive and would be coming home.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here