THIS weekend exactly 100 years ago, a million or more men were pitched into a battle which precipitated the end of the First World War a fortnight later. Of those million or more fighting to the north of Venice, one stood out: a pitman from Murton on the east Durham coast.

He was Sgt William McNally whose “innumerable acts of gallantry set a high example to his men, and his leading was beyond all praise”.

So beyond all praise was it that he received a Victoria Cross – Britain’s highest award for military gallantry. It is an award that will be commemorated today with the unveiling of a paving stone in his honour in his home village.

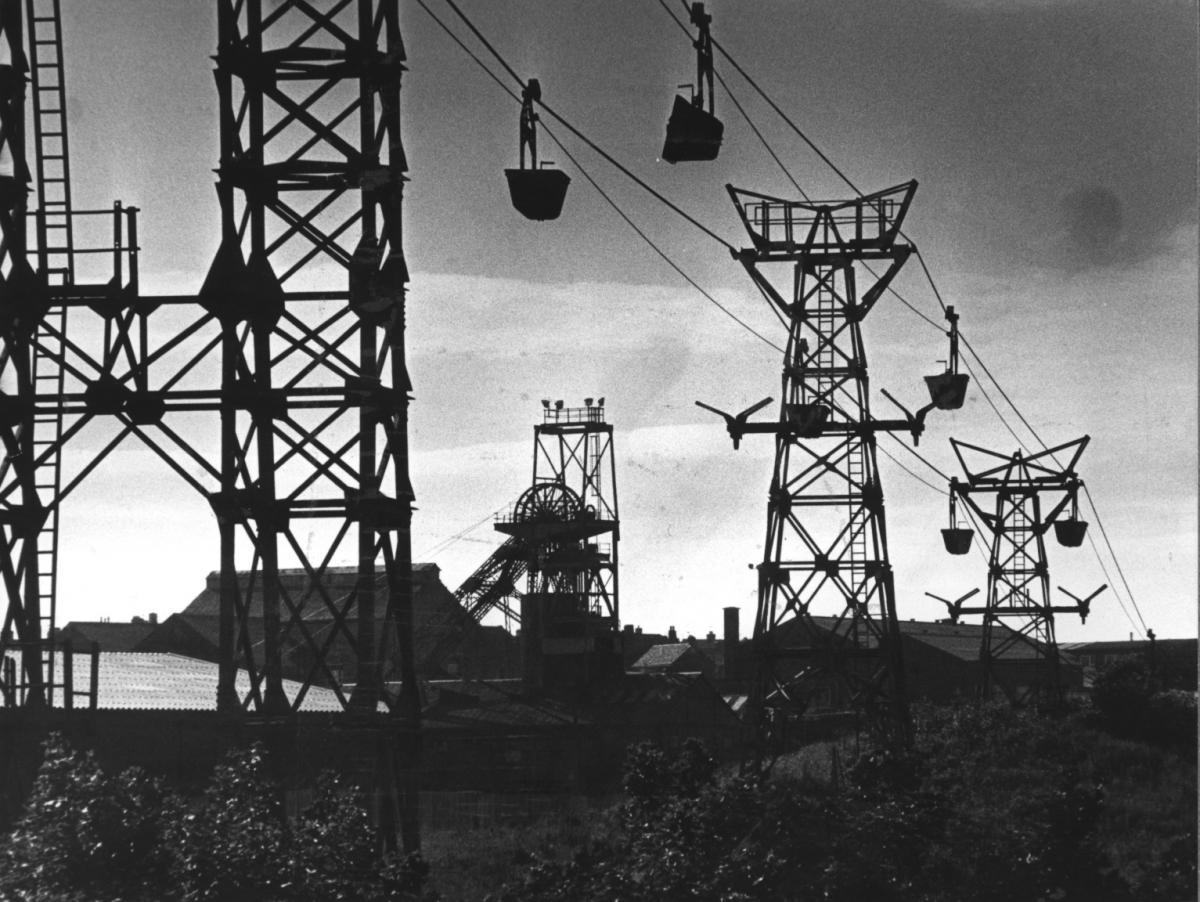

He was born there in December 6, 1894. After leaving Murton Colliery School at the age of 14, he followed his father down the pit and worked as a pony boy. But when war broke out he was 20, and he enlisted immediately at Sunderland, joining the 8th Battalion of the Yorkshire Regiment – he became a Green Howard.

He arrived on the Somme in July 1916 and won a Military Medal at Contalmaison when he dragged a seriously wounded officer to safety, while administering first aid.

McNally remained on the Western Front and next came to his superiors’ attention in early November 1917 when, at Passchendaele, near Ypres, on three occasions he rescued men who were either wounded or who had been buried by enemy shellfire. For his gallantry, he was awarded a bar to his Military Medal – in effect, a second gallantry medal.

The battalion was then sent to northern Italy where the River Piave formed a natural frontline between the Italians and the Austro-Hungarians, who were allies of Germany. During the summer of 1918, the Austro-Hungarians tried to burst through the Italian lines and march south down the Italian boot.

But the Italians, perhaps surprisingly, held strong, inflicting heavy losses on their enemy. Allied commanders wanted the Italians to turn the tables, cross the river and chase after the Austro-Hungarians, but the Italians refused, preferring to bide their time...

The empire, said one of their spies, was “like a pudding which has a crust of roasted almonds and is filled with cream. The crust, which is the army in the frontline, is hard to break”. But due to the cream, it was softening all the time.

On October 24, 1918, the Italians launched their assault on the crust. They had about 1.4m in their armies augmented by 40,000 British soldiers – including the Green Howards – plus several thousand French, Polish and American men.

But the crust had about 1.8m almonds.

It took five days to crack, during which time the Durham pitman exhibited his bravery on three more occasions.

On October 27, at the Battle of Vittorio Veneto, McNally’s company was “most seriously hindered in its advance by heavy machine-gun fire from the vicinity of some buildings on the flank”, according to his VC citation.

“Utterly regardless of personal safety, he rushed the machine gun post single-handed, killing the team and capturing the gun.”

Two days later he was nearby at Vazzola “when his company, having crossed the Monticano River, came under heavy rifle and machine-gun fire. Sgt McNally immediately directed the fire of his platoon against the danger point whilst he himself crept to the rear of the enemy position.

“Realising that a frontal attack would mean heavy losses, he, unaided, rushed the position, killing or putting to flight the garrison and capturing a machine gun.”

He was not finished yet. “On the same day, when holding a newly captured ditch with 14 men, he was strongly counter-attacked from both flanks. By his coolness and skill in controlling the fire of his party he frustrated the attack, inflicting heavy casualties on the enemy.”

And so the battle was won. The Italians lost about 7,000 men killed, and the British lost 2,139, but the Austro-Hungarians had 30,000 men killed, 50,000 wounded and about 500,000 taken prisoner.

For them, the war was over, and for Austro-Hungary, the game was up. Hungary and other parts of the empire melted away from Austria on October 31. At 3.20pm on November 3, Austria – Germany’s principle ally – signed an armistice and withdrew from the war.

Germany was now alone, and facing defeat in the face – defeat which formally came at 11am on November 11.

On December 15, McNally was rewarded for his part in the kaiser’s downfall with a Victoria Cross, which was presented to him the following summer at Buckingham Palace by King George V.

By then, this thrice-honoured and thrice-wounded soldier had been demobbed and had returned to the pit.

On November 11, 1920, he was part of the VC Guard of Honour in Westminster Abbey for the interment of the Unknown Warrior, and during the Second World War, he was a lieutenant in the Murton Local Defence Volunteers – Dad’s Army. This epithet was appropriate as McNally had six children, 11 grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren.

He retired from the colliery in 1958 when he was 65 and timber-yard foreman. He had spent his last working years fashioning pit props.

When he died in 1976, aged 81, £2,000 was collected and on October 28, 1978, a memorial was unveiled by his widow, Elizabeth, on Murton village green.

“I am overwhelmed by this, but very proud,” she told The Northern Echo. “I am sure my husband would have felt the same.”

The Reverend Brian Pateman, of Holy Trinity Church, said: “This memorial is a reminder of a man from our community who, when it was demanded of him, set his face upon an objective and a purpose.”

Similar words will surely be said today when he is remembered as part of the Government’s plan to commemorate every VC winner on the 100th anniversary of their award.

Today’s ceremony is at 11am at the cenotaph and is followed by a free exhibition about his exploits at the Glebe Centre which is open on Sunday and Monday from 10am to 4pm.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel