SIXTY years ago today, The Northern Echo reported that 75-year-old Hannah Macmillan of Fylands, near Bishop Auckland, had died – and with her died a 150-year-old mining community.

Hannah had lived at Fylands for more than 55 years and steadfastly refused to move, even when the local council condemned the two terraces that made up the village, even when all but three of the houses were demolished by bulldozers.

According to the Echo, she “had in her mind her desire to finish her days in her old surroundings” and so, for the last three years of her life, she was allowed to live at Fylands with only an empty house on either side for company.

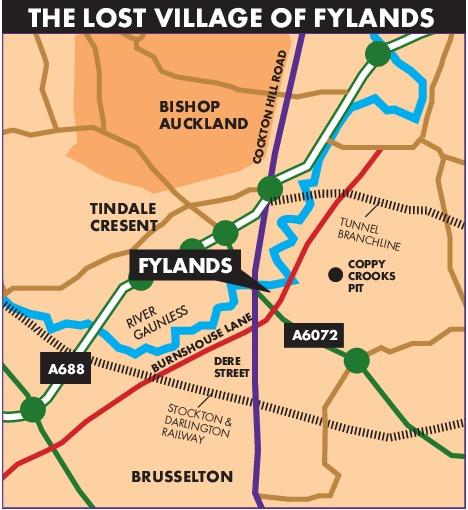

Fylands was at the foot of Brusselton bank – now the A6072 has obliterated nearly every last sign of its existence.

It was initially known as Fieldon Bridge, a name that Ordnance Survey maps and railway companies stuck with into the 1980s although local people knew it as “Fylands”, and that is the name for this low-lying area on maps today.

It was probably an ancient settlement as it was where the Roman road Dere Street crossed – forded – the River Gaunless on its way from Piercebridge to Binchester.

But in 1838, a chap called Luke Simpson built two rows of miners’ homes on the south-western bank of the Gaunless – the first row was called First Row and so you can probably guess the name of the second row. There were 41 houses, each having a wooden ladder to their upper storeys, although staircases were added later.

No 26 Fylands, an end house, was built with cellars as it was intended to be a pub, although it was never licensed.

The houses were for miners working at Coppy Crooks Colliery, which was a mile up the bank on the outskirts of Shildon. On October 27, 1849, hewer Gibson Teasdale was crushed by a fall of stone in Coppy Crooks which fractured his spine, although the poor fellow clung to life until May 26, 1850 – the Durham Advertiser reported that his inquest was held a day later at “Filand Bridge”.

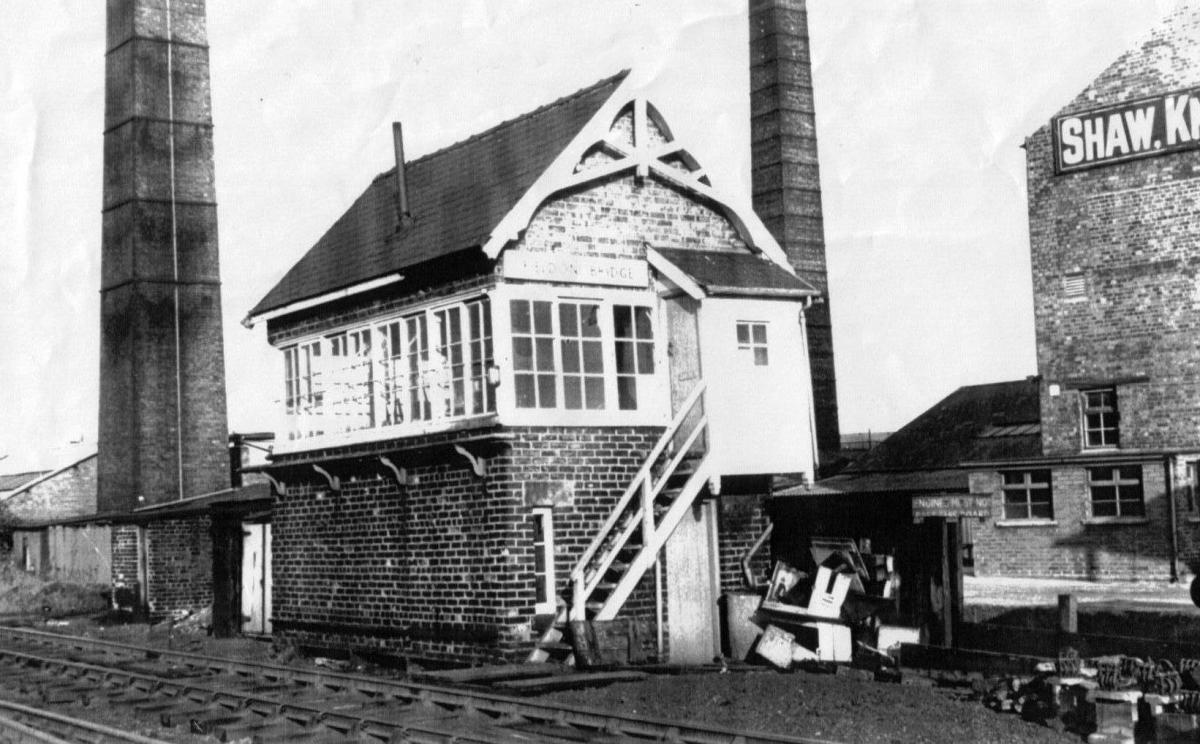

As the 19th Century wore on, a chapel dedicated to St Luke was built near Fylands, and a school for 70 or so children was added. In 1885, the West Auckland railway shed was opened by the North-Eastern Railway on the nearby Bishop Auckland to Barnard Castle branchline, and its movements were controlled by the “Fieldon Bridge” signalbox.

At the start of the 20th Century, the Fylands brickworks was opened to exploit the clay which generations of people had scooped out of the ground near the Gaunless. Tragically, such works left water-filled pools, and on May 20, 1918, brothers George and Robert Coulthard drowned while swimming in the brickyard – Robert was 16 and George, 19, had just been released from the Army to help with agricultural work.

The Fylands brickworkers lived in a small run of houses called Dilks Street, so Fylands’ population peaked in the 1930s at around 225 (presumably the owner of the brickworks was a Mr Dilks).

The brickworks was shortlived, though, and in 1921 Shaw, Knight & Co moved onto its site. It was a “sanitary fireclay manufacturer”. It used the “segger” – the layer of heavy buff-coloured clay that lies beneath a coal seam in much of south Durham – to make urinals, sinks and mortuary tables. By 1939, Shaw, Knight had 170 employees and owned two coalmines to the west of Esh Winning, at Hedley Hill and Ivesley Lane.

Shaw, Knight also become a Bishop Auckland landmark due its four tall chimneys, with its initials on, beside the railway line.

Yet the early mining terraces of Fylands – which were largely occupied by men connected to the South Durham Colliery in Shildon – were looking their age.

In the early 1950s, “Shildon Urban Council decided that the houses were unfit for habitation and all the families excepting one were rehoused at Shildon and their houses demolished to ground level”, said the Echo.

That one, of course, was Hannah.

Hannah was born at Brotton into a mining family, and moved to Fylands after her marriage to Joseph Macmillan, a south Durham miner. It was in Fylands that she had her three children, and it was in Fylands that she became a grandmother, as her daughter Olive gave birth in 1943 in a neighbouring house to Heather, who now lives in Bishop Auckland.

And it was in Fylands that Hannah died after 58 years – a lifetime from being a young wife through to being a mother, a widow and a grandmother.

“Mrs Macmillan was adamant about finishing her days at Fylands and, despite constant overtures by her son, she got her desire,” said the Echo on October 20, 1958.

“Her sudden death at the age of 75 has made the end of Fylands possible, and the remaining three houses, two of which have been vacant for more than three years, will be knocked down after Mrs Macmillan’s funeral tomorrow.”

Appropriately, her funeral was in St Luke’s chapel. It must have been one of the last services at the chapel because it was soon converted into a garage and then, along with the school beside it, demolished.

Shaw, Knight also lasted into the mid-1960s. Two of its chimneys were demolished in 1969 and the last two remained until the mid-1970s, as the site was remodelled as the Roman Way industrial estate – in fact, we believe that its draughtsmen’s offices survived the clearance and are still in use.

The barest outlines of the mining community of Fylands can still be traced beside the Gaunless, although the residential nature of the area has not entirely been lost.

Dilks Street still stands, with a terrace of eight houses, beside the A6072. It leads to the site of the Fylands brickworks on which now stands the most extraordinary home in south Durham: the four-storey art deco mansion of Tindale Towers, which won architectural awards when it was completed in 2008 by Mike and Jules Keen, who run a furniture manufactory.

It was recently on the market for £3.65m when, according to the estate agent’s blurb, it offered “every imaginable extravagance”: a shaped indoor swimming pool with adjoining Jacuzzi and sauna, plus a dance floor, a cinema screen, electrically operated soft furnishings and self-tanning showers.

Never can there have been a greater contrast between the opulent luxury of Tindale Towers and the crudeness just a couple of hundred yards away of the mining terraces of Fylands Bridge with their ladders for staircases.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules hereLast Updated:

Report this comment Cancel