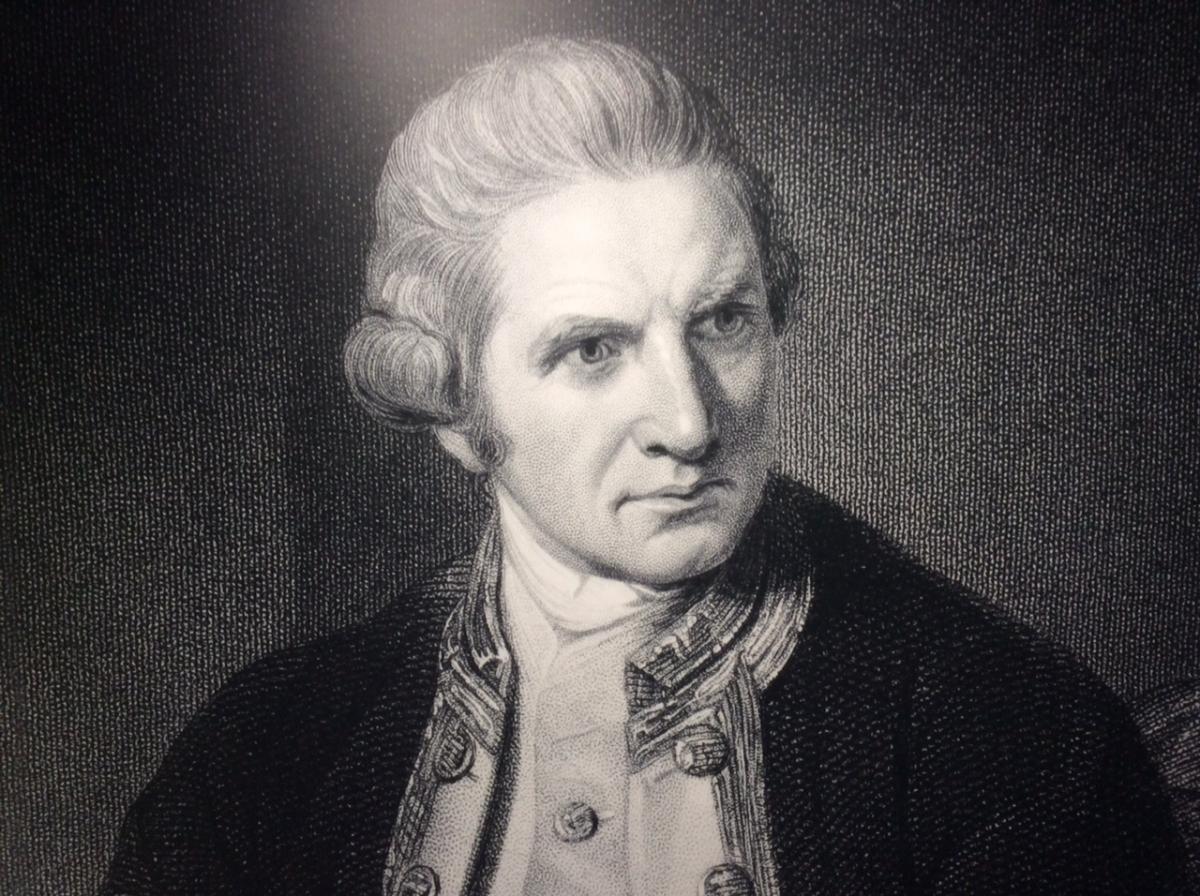

This summer, the 250th anniversary of the start of the first of Captain James Cook’s three historic voyages is being commemorated in communities connected to him around the world. Jan Hunter traces his rise from humble beginnings to global fame

HOW did a young boy, who began his life in poverty, become a naval captain, cartographer and navigator? What happened in those formative years to produce one of the most famous explorers in British history?

In the early 18th Century, there was a strict class system, and it was unusual for anyone to rise above their station. Sons inherited their father’s position in society and James Cook, the second son of farm labourer James Cook, was born in Marton, in a cramped, damp, mud house with no money, into a family whose only ambition at the time was to survive. There was nothing to suggest that from such beginnings he would grow up to be one of the most enduringly famous people on the planet.

“James Cook had no claim to distinction on account of the lustre of his birth or the dignity of his ancestors,” said the Reverend Andrew Kipps, who was Cook’s first biographer in 1788.

Only a little is known about James Cook’s father. Originally from Scotland, he came to England to find work as an itinerant agricultural worker. He was, though, literate, and when young James was five, he sent him to Dame Walker at Marton Grange Farm, to learn to read and write.

James Cook senior and his wife Grace, originally from Thornaby, moved frequently to find better jobs and living conditions for their growing family. Perhaps young James got his drive and ambition from his father, as in 1736, the family moved to Aireyholme Farm in Great Ayton, to live in a farm cottage on the slopes of Roseberry Topping. James Cook senior became a “hind”, an overseer of the farm, which was a job with responsibilities. The landowner was Thomas Skottowe, who lived at Ayton Hall, and he would play an important role in the young James Cook’s life.

The site of this cottage has been traced thanks to the Great Ayton Community Archaeology Project. Its members received information from the Martin family, tenants of the farm since the mid 19th Century. It was probably while living there that young James caught his first sight of the sea, as he climbed to the top of Roseberry Topping, or Ounesbury Topping as it was then known.

James was sent to the Postgate school in the village, at the expense of Thomas Skottowe who, according to the stories, saw the boy’s potential. It is now the Schoolroom Museum in Great Ayton, and is well worth a visit.

“Cook must have had a good grounding here, especially in arithmetic during the four years he was at the school,” says local historian, Dan Sullivan, “as he was able to become a shop assistant at Staithes when he was 16. Later, with some tutoring, he was able to teach himself surveying, navigation or even astronomy.”

Graves in his 1808 History of Cleveland presented his gleanings about Cook’s boyhood. He says that Cook wasn’t one of the boys but was always an individual with his own plans and schemes. “There was something in his manners and deportment which attracted the reverence and respect of his companions,” wrote Graves. “The seeds of that undaunted resolution and perseverance were conspicuous even in his boyish days.”

The man who employed him as a shop assistant in Staithes was William Sanderson, a friend of Thomas Skottowe. How Cook eventually came to leave this employment is unclear.

“James Cook now lived by the sea – he was living the dream, but not quite,” says Jenny Phillips, Education Access Officer at the Birthplace Museum. “Did he leave of his own accord? There were rumours that he stole a South Sea silver shilling. Was he becoming mixed up with the smuggling gangs in Staithes? Perhaps Mr Sanderson give him the push he needed, as he too saw his potential, and he was soon apprenticed to the Quaker ship owner, John Walker, a friend of Mr Sanderson’s, and master mariner at Whitby.”

It seems unlikely that John Walker, a strict Quaker, would have employed a thief. It is also said that Cook was known for the Quaker values of honesty, caring for others and straight dealing. He looked after the men on his ships. It is more likely that Mr Sanderson saw that his young assistant’s ambition lay elsewhere and he helped him to achieve it.

Whitby at this time was in the midst of an economic boom. It was a major ship building location. Whitby schools taught all the subjects necessary to join the merchant navy; mathematics, trigonometry, astronomy the use of logarithm tables, navigation drawing and merchant accounts.

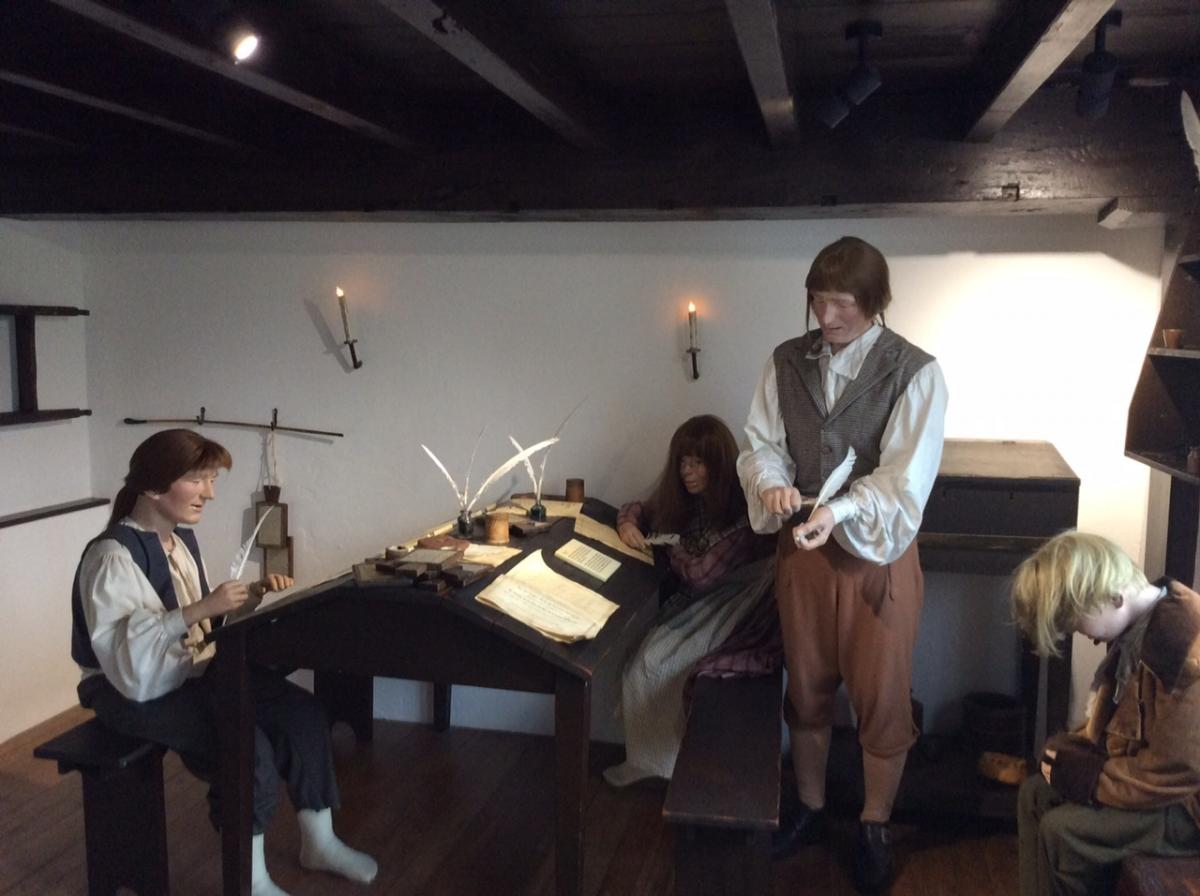

“James Cook wouldn’t have attended these schools,” says Charles Forgan, of the Captain Cook Memorial Museum at Whitby. “He was having his practical experience on board Mr Walker’s ship, so he would study from text books in the evenings, perhaps transferring his knowledge to a ciphering book.”

It is known that Walker’s housekeeper, Mary Proud, who was very fond of the young man, gave him extra candles so that he could study at night.

He was to spend nine years in the merchant navy, most of which was serving on John Walker’s Whitby colliers. The Museum in Whitby gives a fascinating insight into the life and times of these young apprentices.

“He was a useful, strong lad, learnt quickly and Walker was thinking about giving him his own ship,” says Charles Forgan.

However at the age of 27, James Cook decided to quit and join the Royal Navy, helped on his journey by his influential patrons, Thomas Skottowe and local MP William Osbaldeston, and with the blessing of Mr Walker.

“He knew war with France was about to start,” says Dan Sullivan, “ and this could mean excitement, the chance of prize money and rapid promotion, due to his extensive experience at sea.”

He joined Hugh Pallister, captain of the HMS Eagle, who was to become his patron in the Royal Navy, and his new career began, and fame that would last for centuries beckoned…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here