One of the most serious incidents ever at Northallerton jail was a mutiny of military prisoners in 1946. In the final part of a series on history of the site, Hannah Chapman looks back at the “glasshouse riot”, and the events leading up to it

THE mood in Britain’s military prisons, or glasshouses, after the end of the Second World War was angry, to say the least.

Aggrieved that they had not been released, despite months passing since the war finished, many decided they had simply had enough.

At Northallerton Prison, which had been used as a glasshouse since 1943, the frustrations boiled over in early 1946.

On February 3, after Sunday service, there was a mass breakout.

The Northern Echo reported: “Sixteen of them made a concerted rush from the ranks to the doors giving access to the yard of the prison from Crosby Road.

“The officers in charge of the men were helpless to stop this mass breakaway as they carried no firearms or weapons of any sort. As soon as the men gained the street they scattered in all directions for the open country.”

The alarm was raised with North Riding Police, and many of the men were captured a short time later on Thirsk Road. Before nightfall, 12 were back in custody.

A week later, there was a second mass escape. Thirty prisoners made a dash for freedom – although about half thought better of the escapade and went straight back inside.

Sixteen inmates remained on the loose, sparking an intensive search by police and the military authorities. Fourteen were soon back behind bars, two after making the 45 miles to Leeds.

The Northern Echo told the story. “Mr C B Ayre, transport contractor, Northallerton, said that his attention was drawn to the prison by rioting which seemed to be going on within the building about 2 o’clock on Saturday afternoon," said the paper. "This was followed shortly by the smashing of the window at the south end of the central building, which is three storeys high.

“The men broke out from the second floor and he saw them drop from the window to what he took to be the prison yard, 15 feet below. A few minutes later the corrugated iron doors on the south side of the prison were smashed and the prisoners rushed out into the street.

“A hue and cry for the escapees were raised and North Riding Police were summoned from all parts of the county.”

The authorities were struggling to find trained staff to man the prison due to the demobilisation of the military police.

The Echo said: “The guards are unarmed, even without truncheons. They turned hose pipes onto the prisoners as they were escaping on Saturday, and even this did not deter them.”

“Drastic action” was taken against the ringleaders of the prison break – they were sent to Durham.

Two weeks later, a "mutiny" at Aldershot – the original glasshouse, named because of its glazed roof – was blamed on half a dozen Northallerton "bad men" who had been transferred there after the jailbreaks. After a 24-hour riot, the prisoners set fire to the main block in a last gesture of defiance before surrendering, “hooting derision” at members of the Army Fire Service.

Lieut-Gen Sir John Crocker said: “These men have shown every sign of indiscipline and desire to repeat here the incidents that occurred at Northallerton. I believe myself that the root of the whole thing lies there.”

War Secretary JJ Lawson agreed, telling the House of Commons that two men from Northallerton started the riot.

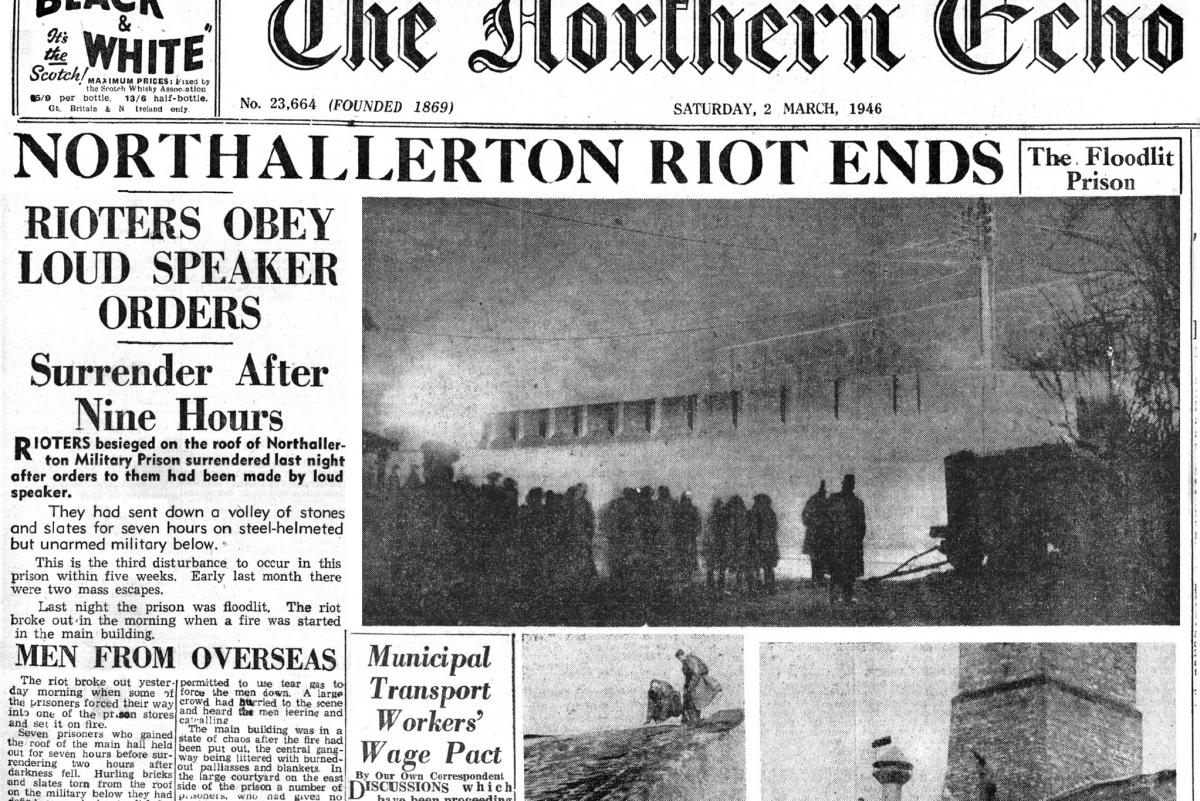

ON the morning of Friday, March 1, the powder keg that was Northallerton exploded, ignited by a small group of prisoners who had arrived from overseas just two days earlier.

“Pandemonium broke out following an assault by one of the prisoners on a guard, and the main building was set on fire,” reported The Northern Echo.

The unarmed guards retreated. Seven prisoners made it onto the roof of the main hall, where they spent the next seven hours “hurling bricks and slates torn from the roof on the military below.”

Fifty armed troops from Catterick Camp had rushed to the scene but were forbidden to shoot, or use tear gas.

Extra police had to be called in to control the large crowd which had gathered, listening to the men "leering and catcalling".

To the guards turning fire hoses on them, they shouted: “Have you got no water left? I want a wash.”

Another, watching debris being cleared from the yard, yelled: “What are you sweeping up for down there? There’s plenty more coming down."

The 300 non-rioting inmates were transferred elsewhere – many to Nissen huts in the prison yard.

The occupants of one hut broke down the door and set fire to their bedding. Feeling sorry for their drenched comrades on the roof, they sent up a bucket of tea on a rope.

The rebels were forced to take shelter for a time by the fire hoses, but when darkness fell they re-established themselves on the roof, despite floodlights being brought in by the authorities.

The Echo painted a picture of the destruction: “The main building was in a state of chaos after the fire had been put out, the central gangway being littered with burnt out palliasses and blankets. In the large courtyard on the east side of the prison a number of prisoners, who had given no trouble, played football while the men on the roof were stripping the slates and woodwork. Every window in the top floor was broken.”

The War Office was at pains to point out no prisoners gained access to the armoury, but the siege was not without victim – two firemen were injured by missiles thrown from the roof and a police sergeant was knocked unconscious by a stone.

By 5pm, nine prisoners were on the roof and appeared to be settling in for the night.

But their mood changed two hours later, following an appeal by Brigadier LS Lloyd, commander of the Catterick and North Riding sub district.

He told them: “My advice to you is to surrender now. If you have any grievances, I assure you they will be fully investigated and dealt with fairly.”

At first the only answer was abuse, but eventually, they took him at his word. After threequarters of an hour of discussion, they quietly surrendered, bringing to an end one of the most dramatic period’s in the prison’s long history.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here