HE was a young sailor from Shildon, thought the Falklands War into which unexpectedly he was pitched to be akin to England v Argentina at football, returned seemingly unscathed to Civvy Street.

Discharged after five years Royal Navy service, Terence Laheney built a successful career in teaching and a flourishing business in farming but, at the start of 2014, was struck as suddenly and as devastatingly as if by an Exocet missile.

Thirty-two years after the war ended, he developed post-traumatic stress disorder.

“For 18 months I was in a very, very bad place,” he recalls. “Often I had suicidal thoughts. I would sit for four or five hours looking out of the window and not know that a moment has passed.”

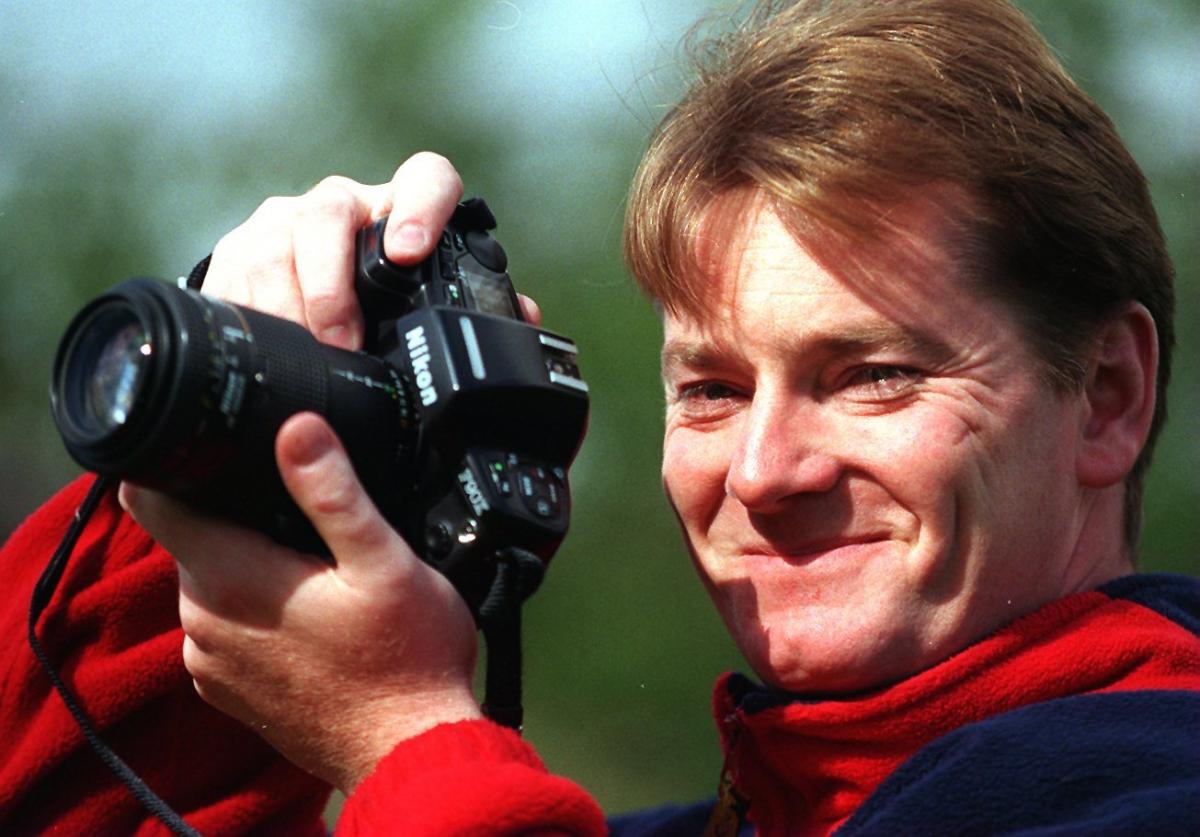

His recovery, gradual and incomplete, has been helped by sharing some of the extraordinary photographs which he took around the battle zone and which appear in the new issue of the Royal Photographic Society Journal.

The headline’s “Inside my head there’s a war zone” – and since that fearful breakdown in the office at the Eastbourne Academy in Darlington, he has been unable wholly to find peace or to return to teaching.

“I thought of myself as a pretty cool customer,” says the 56-year-old. “Teaching wasn’t stressful, it was an absolute doddle. I got on brilliantly with the kids. Now I don’t even like leaving the farm.”

"Crackers” about photography from the age of 12, he’d abandoned thoughts of a camera bag career and, like all but two of the lads in his comprehensive school class, began an apprenticeship at Shildon Wagon Works.

“My dad had paid £17 for my first camera, a Zolti from McKenna and Brown’s in Bishop Auckland. He knew how keen I was so at Christmas the following year paid £30 for a second hand Pentax. My mam went mad, she thought it was an awful lot for a camera.”

After a year at the wagon works he joined the Navy, very likely to see the world, was serving on HMS Fearless off the West Indies – weapons electronic mechanic, teleprinters mainly – when war seemed imminent and the ship returned to Portsmouth.

“The Royal Navy was an absolutely fabulous life until Maggie Thatcher went and spoiled it,” he says, cheerfully enough, though 'Fearless' still seems somehow appropriate.

“They were very different days. Half the country knew so little about the Falklands Islands they thought they were somewhere off the north of Scotland.

“If you were going to Afghanistan or somewhere today you’d know something about it but then there was no internet, no mobile phones.

“The top and bottom of it was that I was a Shildon lad, I was British and it was like a Boys’ Own story, we were going there to throw them out. I totally believed in what we were doing.

“I think we were very excited. Some older people were leaving family members behind and might have thought differently but to us there was still that football mentality.

“We probably thought we were going to end up invading Argentina. You just wanted to do it.”

A normal complement of 250, the Fearless had 1,100 personnel when it reached the Ascension Islands and they learned of the attack on HMS Sheffield – “that’s when started to think it was becoming real”.

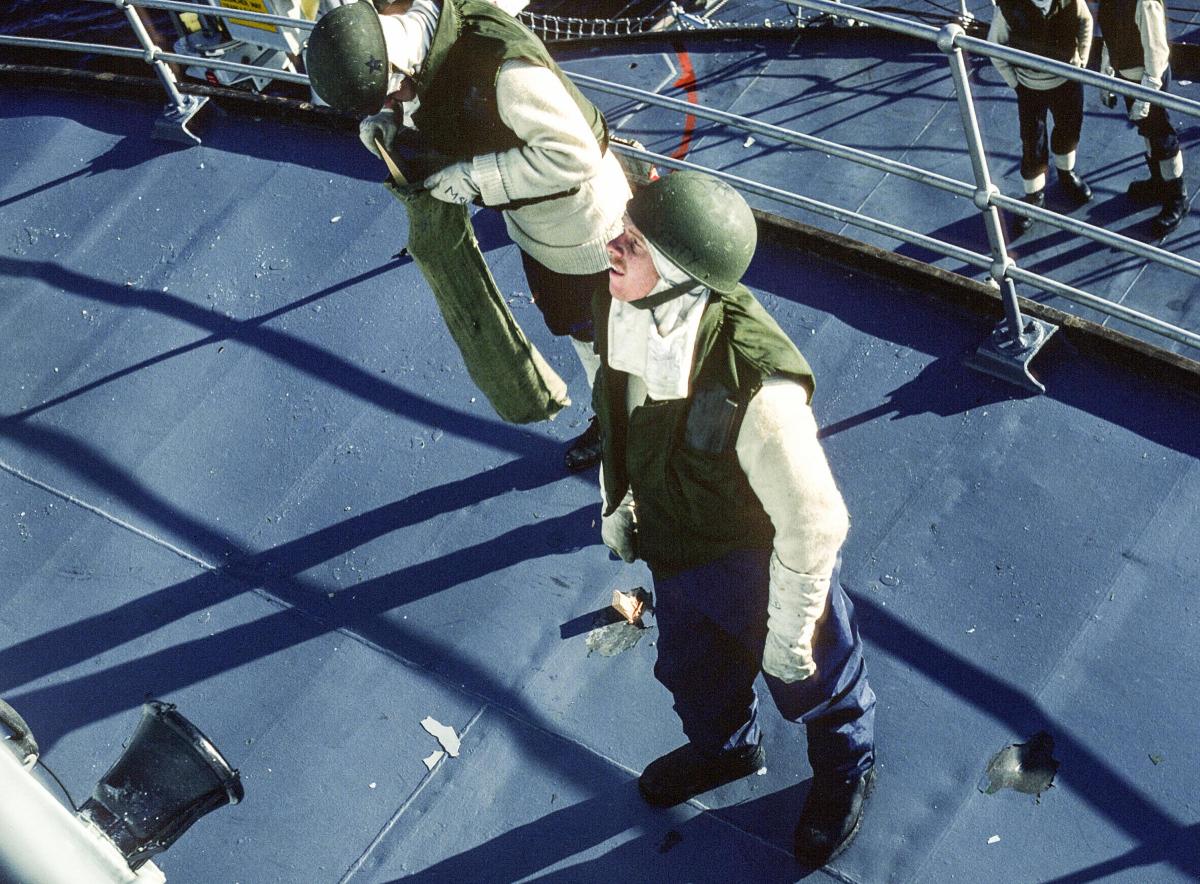

Soon afterwards were in San Carlos Bay, known graphically as Bomb Alley, the teleprinter mechanic manning a light machine gun as the ship’s hull was strafed by 30mm cannon fire.

“It was like someone banging on your door with a sledge hammer. I don’t think I’d handled a machine gun even in basic training; I was into teleprinters, I handled daisy wheels.

The 25-acre farm at Dalton remains a greatly peaceful place, fat hens pecking around the back door, dogs excitedly at his feet.

For Terence, an Associate of the Royal Photographic Society, the reversion therapy of those Falkland images has played a key role in his slow recovery. He’s had help from the Combat Stress charity and the Catterick Garrison-based Beacon housing project, where voluntarily he teaches photography to former military personnel.

“It’s brilliant,” he says. “I’m teaching again and no Ofsted to worry about.”

“For the first few weeks we were a sitting target. The captain was absolutely brilliant, he really was. He’d sometimes appear in plus fours and a deerstalker, a bit eccentric but people loved him for it.”

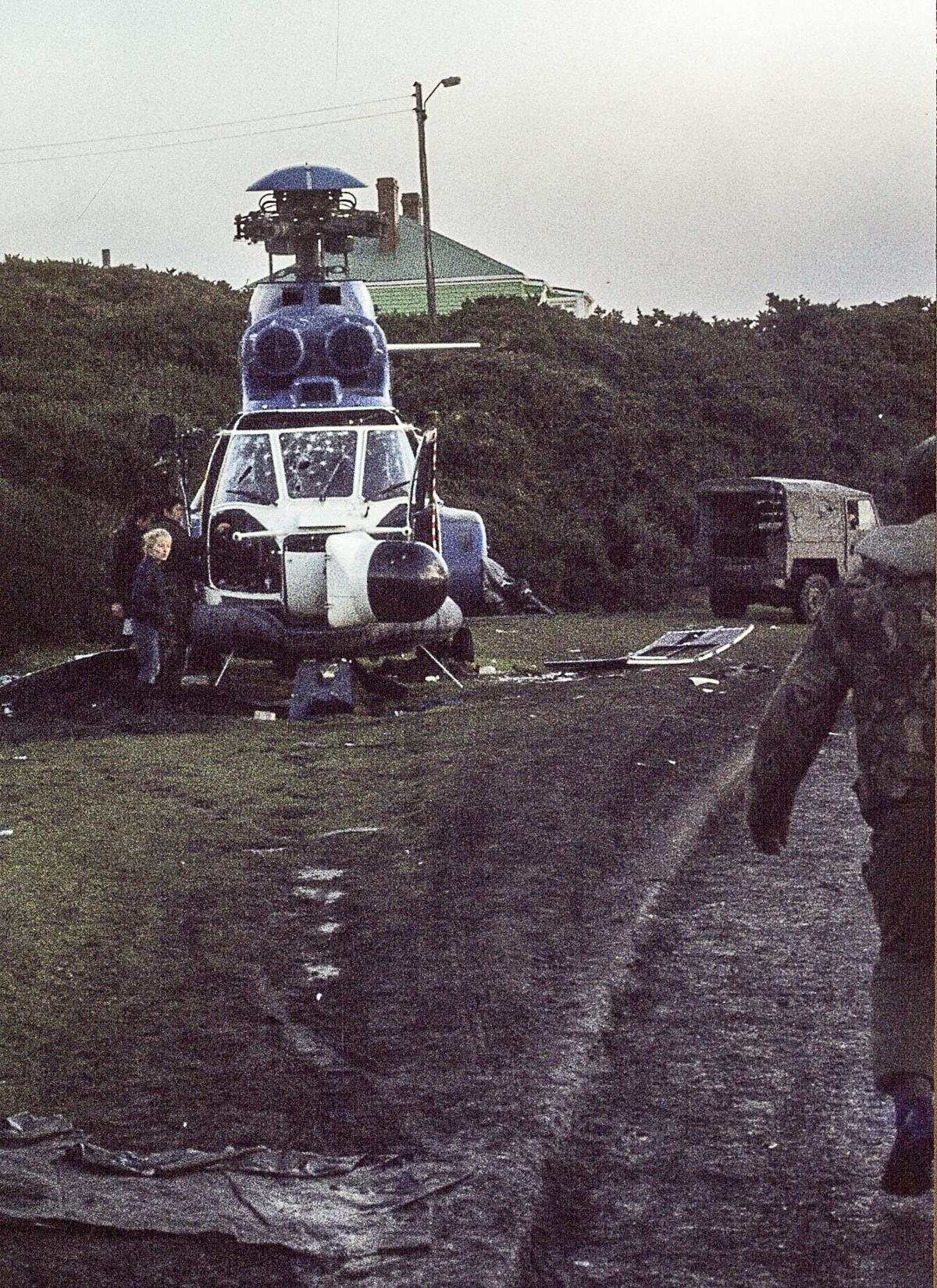

On May 23 1982 he watched as HMS Atlantic was sunk – “I remember getting on the upper deck and seeing all the lads in the water, in darkness. It was horrendous” – soon afterwards landed on the islands and saw Argentinian casualties in a mortuary.

They were the first dead bodies he’d seen, but for Terence Laheney, life went on.

Only two press photographers had been embedded with the Falklands task force, just over 200 images released for publication.

Alternatively armed with a Nikon and an Olympus, and with an officer’s permission, Terence shot almost at will – including Argentine quarters on the Falklands. “We kept pigs, but I’d never keep them in conditions like that.”

Rolls of Kodachrome were finally left with the postmistress at Port Stanley, who agreed to send them back to Shildon. “It wasn’t that I was trying to hide anything, just that my pockets were getting a bit full of film.

“It was just stuff to show my mates back home. When I came back on leave I found them on the doormat. They might almost have been forgotten.”

Permanently ashore, he took a photography degree at the Cleveland College of Art and Design, then a teaching degree (“my dad was pretty surprised by that”) became head of creative arts at Eastbourne Academy and with wife Joanne, also a teacher, ran a hugely successful pig and poultry farm at Dalton-on-Tees, a few miles south of Darlington.

“It just got phenomenal,” says Terence. “We knew it had got out of hand one Christmas Eve when we realised we’d even sold our own turkey. That’s when we stopped.”

Teaching continued greatly to be fulfilling, until that dark day in January 2014. “Life was good, I was happy, no worries at all.

“I was sitting in the office when suddenly I started sweating profusely, my whole body shaking, my heart beating so loudly that I thought everyone must be able to hear it. I thought I was having a heart attack.”

A “brilliant” GP in Hurworth at once diagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder more than 30 years after he’d left the Falklands. It was followed by long months of nightmares, waking and sleeping, by out-of-body experiences, by flashbacks of the most fearful kind.

“I told the GP I never got stressed,” he says. “I don’t think I’d ever been angry in my life; I didn’t get wound up. It was a Shildon thing. We got on, we didn’t do that. Fortunately she knew a lot better than I did. It’s been very hard getting rid of the rubbish in my head.”

Still he experiences really difficult days, still depends upon medication, still dislikes going anywhere. “Sometimes I get resentful, everyone wants to be normal. The slightest thing can still affect me but the difference is that I now know what’s happening. When it starts again I can still feel my body shaking. It takes you back, it’s terrifying.”

Outside are imminent signs of spring, on the walls and in his studio examples of his brilliant photography – particularly of birds – high above the sound of a skylark.

“If there’s a skylark,” says the Falklands survivor, “there’s still a lot right with the world.”

l Details of Terence Laheney’s work and photographic courses at terencelaheneyimages.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here