Philip Sedgwick tells the story of the Yorkshireman who was one of the Second World War’s most decorated airmen on the anniversary of his death

SEVENTY-THREE years ago tomorrow, a highly-decorated North Yorkshire airman died in one of the most daring and spectacular aerial attacks of the Second World War.

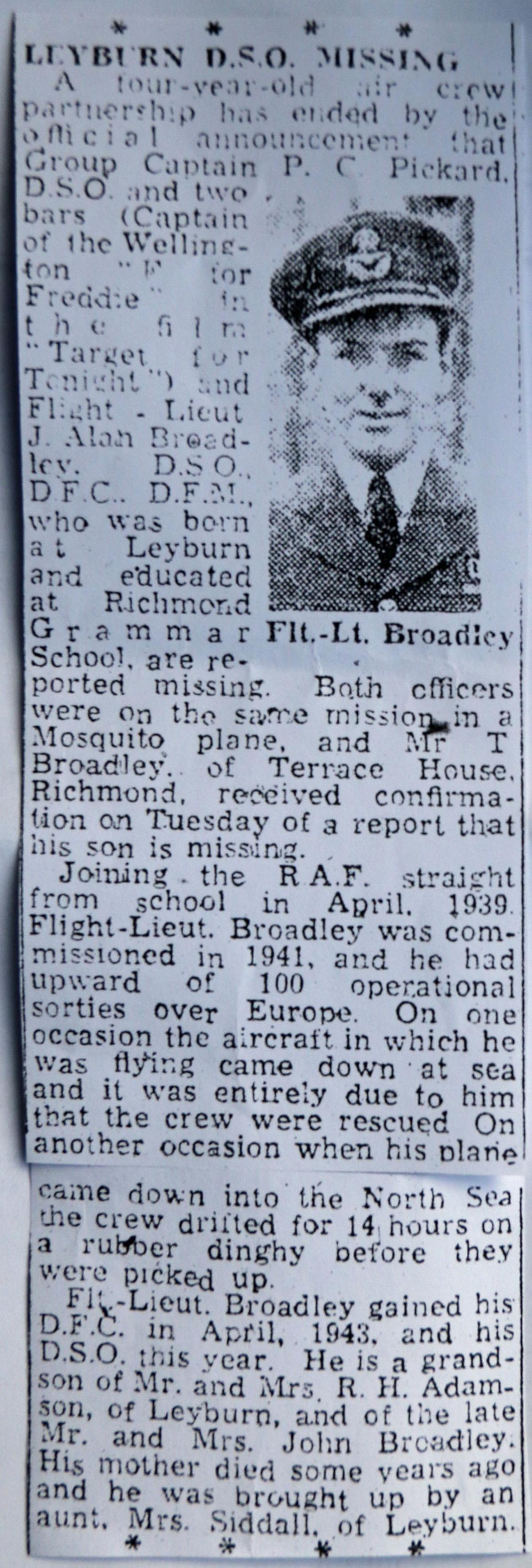

Flight-Lieutenant Alan Broadley was killed having successfully navigated his Mosquito plane on a low-level, high speed raid to break down the walls of a French prison in which the enemy was about to execute 500 resistance fighters.

In all, Broadley flew more than 100 missions over enemy territory, dropping off spies and saboteurs into occupied Europe, and winning three decorations in the process. Such high octane action must have seemed a far cry from tranquil Wensleydale, where he was born on February 8, 1921, in Leyburn – his parents ran the town butchers.

He attended Yorebridge and later Richmond Grammar School, but in response to the gathering war clouds, he joined the RAF. He was initially accepted as a pilot, but qualified as an observer, which was a combination of navigator and air gunner, and he formed an enduring partnership with pilot and fellow Yorkshireman, Charles Pickard.

With the onset of war, they were deployed against enemy shipping in the North Sea and during the evacuation of Dunkirk.

Returning from a mission over Germany, they sustained engine damage and were forced to ditch into the sea. All the crew escaped except the rear gunner who became caught up in wire. Alan bravely plunged into the freezing North Sea to free him, and the entire crew was rescued 14½ hours later after Alan skilfully navigated their dinghy through a minefield.

Pickard became something of a wartime celebrity, starring in morale-boosting films, including Target for Tonight. It is often said that Broadley was also in the film, but he actually missed out on a role as he was away on operations.

Nevertheless, his award of the Distinguished Flying Medal in 1941 was heralded by the D&S Times and in February 1942, in the parlance of the times, he was posted to a new hush-hush outfit, based at Newmarket. Shrouded in secrecy, the unit’s work involved transporting agents and saboteurs for the Special Operations Executive into occupied Europe, and it was extremely dangerous – one of its most remarkable and celebrated raids was dropping paratroopers at Bruneval and capturing German radar secrets.

Most of the time the airmen managed to return unscathed. However, on one occasion, the wheels of the aircraft became stuck in mud and they only managed to get airborne in the nick of time under the noses of the arriving Germans.

And on another mission, Alan made a forced landing in neutral Portugal and was interned. When his flying boots were stolen, he realised that he was in a dangerous position, so he walked barefoot to the Spanish border and arrived back at base a month later.

A further honour came his way when he received a Distinguished Flying Cross which was soon followed by the Distinguished Service Order – up to that point in the war, he was only one of three non-pilots to be given this award.

In February 1944, as the British war effort was gearing towards D-Day, intelligence suggested 500 resistance prisoners held in Amiens prison were to be executed by the Gestapo.

In response, an audacious plan was hatched. Group Captain Pickard was to lead it, assisted by his navigator, Flt-Lt Broadley.

The raid would entail 36 aircraft, low-flying and precision-bombing. It would be called Operation Jericho because it would bring the prison walls tumbling down and so free the 500 doomed prisoners.

Pickard, from Sheffield, and Broadley were to lead the initial airborne assault by 24 aircraft, but then the plan stated that they should fly back over the prison, assess the damage and, if the walls had not be breached, they would call in a further wave of aircraft – this would have been awful decision to make, because this wave was to completely obliterate the prison, killing everybody inside, including the prisoners. It was believed the resistance fighters would prefer to die by British hands rather than German.

On the day of the raid – February 18, 1944 – the weather was terrible and many of the crews thought the operation would be called off. However, they were slung across the Channel low-level at 300mph, and the first Mosquitoes started their approach to the target as the clock on Amiens cathedral struck noon.

However, they were not alone. A crack Luftwaffe fighter squadron, known as the “Abbeville boys” had been alerted to their presence.

In the event, the walls of Amiens prison were breached and many prisoners escaped. But Pickard and Broadley failed to return home.

It later emerged that they had been among the crews who scored a direct hit on the walls but as they returned to assess the damage, they were shot down. They crash-landed in a wood, and their bodies were quickly buried by local partisans.

Recently, as historians have reviewed the war, it has been suggested that Operation Jericho was a diversion for the D-Day landings. Northallerton author Anthony Eaton, who has written several books including From the Dales to Jericho which is an account of Broadley’s life, disagrees.

He said: “Two good reasons appear to counter this story.

“Firstly, it is very doubtful that the RAF chiefs would have deliberately endangered the lives of scores of Mosquito and Typhoon crews by ordering them to take off in a blinding snow storm on what has been described as a ‘spoof raid’ – spoof raids were rarely precision and low level.

“Secondly, the attack date had been postponed several times due to those appalling weather conditions which were putting the reasons of the attack in doubt.”

The Leyburn flier is one of the Second World War’s most decorated airmen who was not a pilot, and Mr Eaton concludes: “Group Captain Charles Pickard and Fl-Lt Alan Broadley, both Yorkshiremen, deserve their place in the pantheon of the history of the Royal Air Force.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here