Jan Hunter reports on a book about a lost nomadic way of life

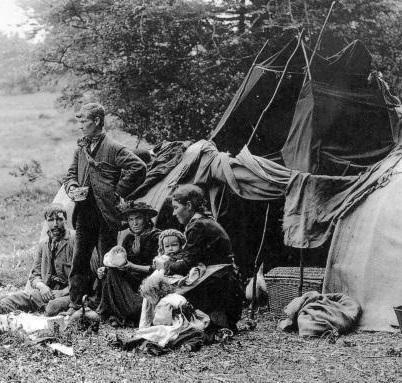

THE Wanderers of the early 19th Century were the contract, or migrant, workers of today. If work was not available in their own community, they had to travel the country to find it somewhere else.

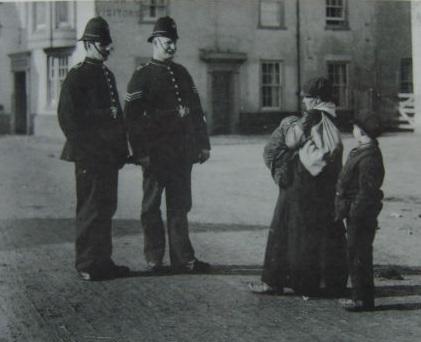

However, as each town and village had its own tight-knit society which looked after its own residents, the Wanderers were often looked upon with suspicion, and were moved on quickly.

But, just as some industries today need migrant workers, so the Wanderers were required in the past. Most market towns had several hiring fairs a year, often so farmers could employ seasonal agricultural workers.

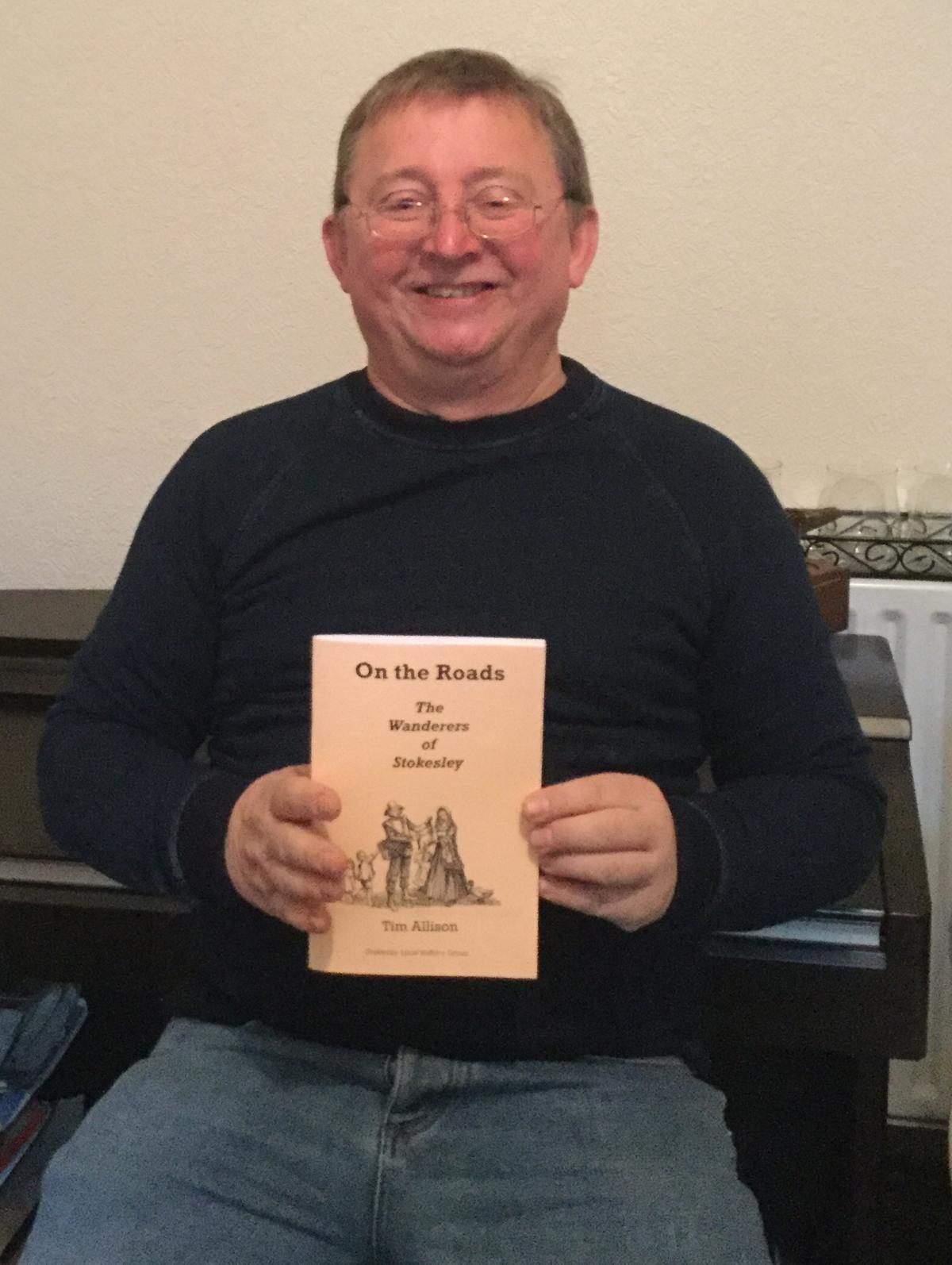

Stokesley had such a fair, which obviously attracted Wanderers looking for work, and their story has been pieced together by Tim Allison, of the Stokesley Local History Group, for his new book, On the Roads – the Wanderers of Stokesley.

“I wanted to find out why Stokesley is like it is now,” he says.” I have tried to explore who these travelling people were, as they were given many names, such as rogues, vagabonds, footpads, hawkers, pedlars and tinkers. The authorities didn’t understand that many people were trying to survive and were actively looking for work, but they were quickly moved on and could be whipped for begging.”

Some people were Wanderers because they were so poor they didn’t even have a roof over their head to tie them to one place, so they went looking for work. However, the 1824 Vagrancy Act made it an offence to sleep rough or beg, so life on the road became increasingly difficult.

The Poor Laws, which were revised in 1834 and mark the start of Tim’s book, identified three classes of “vagrants”: the able poor who could work but had fallen on hard times; the idle poor who could work but wouldn’t, and the aged or infirm poor who were physically incapable of working.

The first two classes could be whipped through the town to discourage them from staying and being a drain on local resources; the third class were placed in the workhouse and given the worst jobs, again to discourage them from staying. Stokesley’s workhouse was built in 1848, replacing a smaller Poor House in College Square. The Wanderers were given the job of picking oakum which was unravelling rope so it could be reused; a job which was very painful on the fingers, and also stone – breaking. To make life as uncomfortable as possible, they were made to sleep on bare boards, in the hope that they would move on quickly. The woods around the towns became increasingly dangerous as rogues and vagabonds, not actively looking for work, were driven away and resided there, living by their own means.

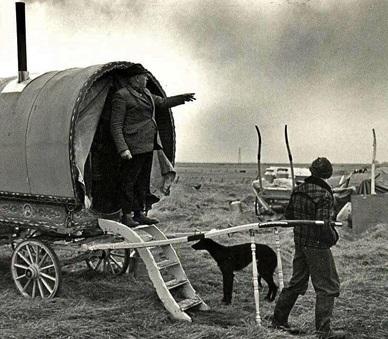

Some people were Wanderers because it was the nature of their culture. Gypsies arrived in England in the early 16th Century. They were initially regarded as a novelty because of the gold they wore and their colourful clothes. They made money by entertaining, selling artefacts and telling fortunes, and they married non-gypsies when they travelled to fairs and markets.

But the authorities didn’t understand their nomadic way of life, and the people were suspicious of them because some who travelled under the guise of gypsies were fake. These people gave the true gypsies a bad name and they were called counterfeit or pretend gypsies. So the force of the law was brought against them to discourage them from staying. For example, on March 1, 1843, police officer Edmund Charles Gernon made a complaint that in the house of Robert Calvert Farrow of Stokesley, Jane Blewitt had pretended to tell fortunes. She was found guilty and committed to the House of Correction in Northallerton for six weeks hard labour.

Some people were Wanderers because they were migrant workers. The Irish found their way into Stokesley, after the disaster of the potato famine in their own country in the 1840s. The census of 1861 records that 13 Irish people had settled in Stokesley, listing their occupations as agricultural labourer, licensed hawker and land drainer.

Offences committed in the town are also listed, hawking without a licence being the most common offence even though the punishment of hard labour was the consequence.

Tim’s research is meticulous and brings vividly to life the various people who travelled the roads in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The census extracts and surname indexes included in the book, enable people to look up their ancestors and discover the trades of the day that people followed.

The Wanderers of Stokesley is a follow-up to the Stokesley History Groups’ last book which was written by Irene Ridley and Daphne France called Deprivation and Poverty, which gave an insight into how Stokesley dealt with its own citizens who had fallen on hard times. Another of the society’s recent publications was the Stokesley Ale Trail, by Tim, which tracked the history of the astonishing number of pubs that once existed in the town.

The society encourages its members to do research, to catalogue photographs and to put on exhibitions. It welcomes new members and details are available on the website www.stokesley historygroup.org, or by phoning the number below.

Tim’s book and further details of the society are available from Chris Bainbridge on 01642-711875.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here