AFTER a talk in the autumn, Janet Binney asked if we knew anything about St Cuthbert’s Well, which is in a field near Scorton, the village with the distinctive village green which is to be found in the triangle which has Richmond, Northallerton and Darlington at its points.

A medieval well with medicinal properties, she said.

Intrigued, Memories pedalled off to have a look.

The well is marked on the Ordnance Survey map, between Moulton and Scorton, closest to the hamlet of Uckerby.

In the 9th Century, a Viking raider called Ukyrri – meaning “restless” in Old Norse – built a farm at Uckerby – so we have Ukyrri’s byr – and a village grew up around him. About 500 years later, the village faded away, leaving only three impressive-looking buildings – Uckerby grange, hall and mill – and some lumps and bumps in the surrounding fields. Because of the historic potential of these lumps and bumps, Uckerby is a scheduled ancient monument, but it has never been investigated – although in 1974, a stone Roman coffin was found there.

A few turns of the Memories’ pedals took us several hundred yards south from Uckerby to the well. The map shows it at a crossroads, where the Moulton to Scorton back road crosses a thin, straight scar: the trackbed of the Richmond branchline.

The nine-mile long railway line opened on September 10, 1846. It branched off the East Coast Mainline at Dalton, near Croft racing circuit, and called at three intermediate stations: Moulton (actually closest to the village of North Cowton), Scorton (actually about a third-of-a-mile away from Scorton, and next to our well), and Catterick Bridge (now beneath a light industrial estate having been, as regular Memories readers will know, being badly damaged in an ammunition explosion in 1944).

It terminated at the superb station at Richmond, now a cinema-cum-restaurant-cum shopping venue which suits the grandness of its railway surroundings. Richmond station, like the three intermediates, was designed by York architect George Townsend Andrews who was closely associated with the York “Railway King”, George Hudson. In fact, the unfortunate Mr Andrews died aged 51 in 1855 after the dethronement of the Railway King.

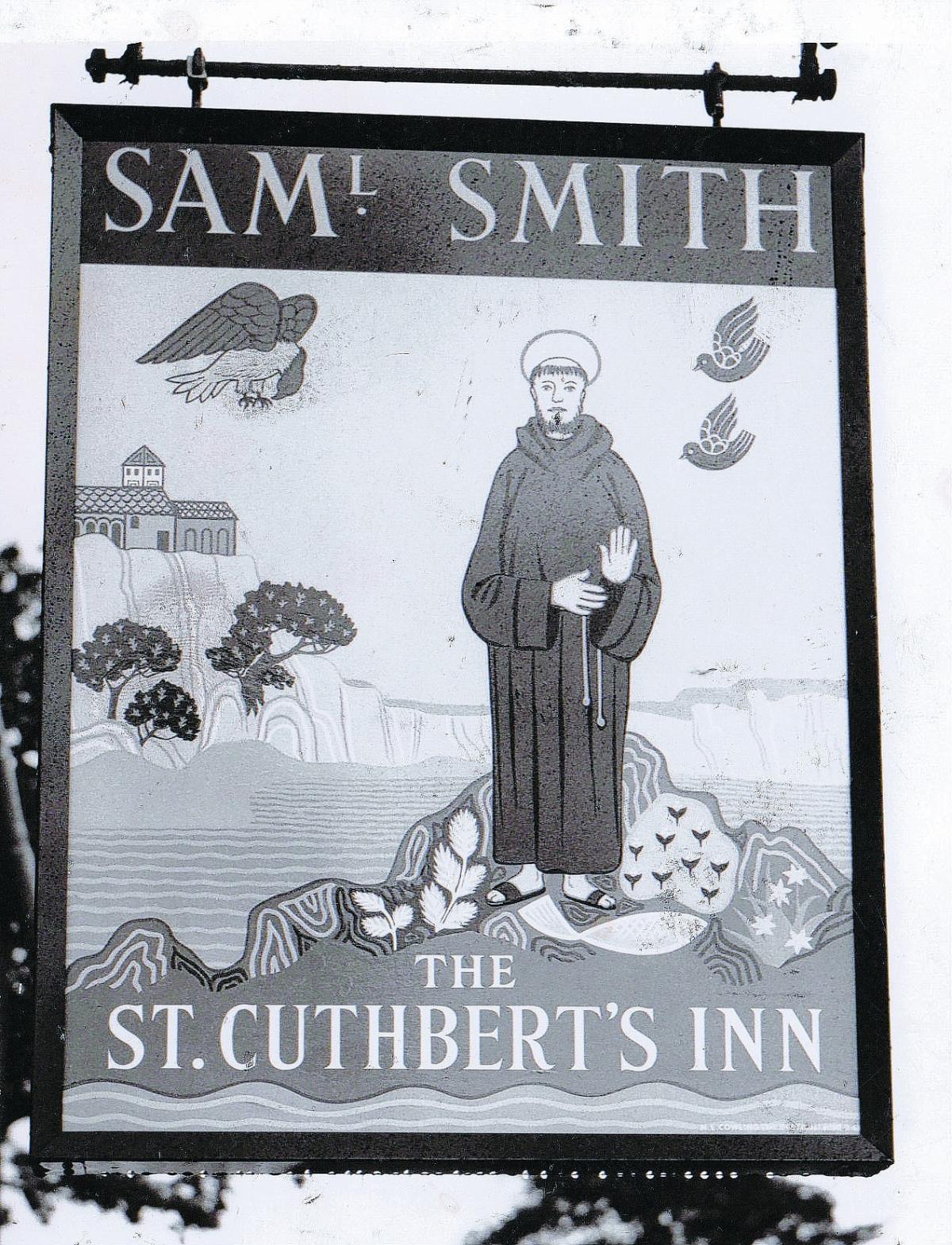

Scorton station is now a private house. Opposite it, there used to be a pub – The St Cuthbert’s Inn – and beside is a footpath which the map said led to St Cuthbert’s Well. Memories dismounted, and, negotiating a rickety wooden fence without a stile, felt like a trespasser, especially as a collection of caged dogs in a nearby house let off a fearful cacophony.

But there was the well, in the lowest point of the field, surrounded by a little wooden fence, and topped by a slate roof with a cross on the top. The well itself is shaped like a keyhole – a few stone steps lead down to a circular reservoir of water.

The well – also called “Cuddy’s Keld” – is named after St Cuthbert, the patron saint of the Northumbria, who had many skills, one of which was dowsing. He is said to have discovered a couple of life-enhancing wells and springs in Northumbria, which bear his name, while he was alive.

Perhaps he discovered the Scorton one when he was dead. In 883AD, his body was carried by his monks as they fled from Viking invaders. Wherever they found sanctuary on their tour of the North-East, Cumbria and North Yorkshire, a church dedicated to St Cuthbert sprang up. A couple of miles up the branchline from the well are the Cowtons – a name means “Cuthbert’s town”. North Cowton got the station, but South Cowton used to have its own St Cuthbert’s Church.

So perhaps at Scorton, St Cuthbert performed a miracle and provided his monks with a thirst-quenching spring. A monastery dedicated to him is said to have grown up around it – although the only evidence of this is a local fairytale – and the well itself was well known for its curative properties. In medieval times, it was particularly efficacious in the treatment of cutaneous diseases and rheumatism, although the heyday of this “noted spring” may well have been the early railway times. The new branchlines gave people the opportunity to explore their locality like never before – and what better daytrip could there be from a place like Darlington than to rattle out to Scorton, take a drop of St Cuthbert’s water, then a couple more drops of the falling down water in St Cuthbert’s Inn before merrily catching the train home?

So effective was the water that even after the Second World War, local people would drink it and patients in Scorton hospital would be prescribed it.

In recent years, drinking out of a hole in the ground has fallen, understandably, out of fashion. Alterations to the nearby beck caused the water level in the well to drop, and its timber and slate housing fell into disrepair. However, it was restored in 2000, and when Memories cycled up to it, it looked to be in pretty good nick.

We didn’t, however, sample the water.

THE inn and the station didn’t fare quite so well as the well. Oh, well.

The Richmond branchline closed on March 3, 1969, and the station was converted into a private house.

St Cuthbert’s Inn gained a reputation for itself as one of the earliest gastropubs when Peter and Julia Edwards were at its helm in the early 1990s. It even got a namecheck in the New York Times in 1993. “If you haven't been to Britain in the last ten years, you've missed a culinary revolution that in some ways has outpaced America's,” said Marian Burros in her Eating Well column. "The revolution has seeped down to the pubs where food has often been an afterthought to go with a pint of ale.” The leading revolutionaries, she proclaimed, were the St Cuthbert’s at Scorton and the Black Bull at Moulton.

Even Mike Amos in Eating Out was impressed. He said of the Sunday lunch: “£10.95 for three courses is relatively expensive, but with the exception of an almost tasteless banana and raisin cheesecake, this is high class fare.”

However, it struggled financially towards the end of the 1990s, was regularly relaunched only to close once more until it shut in 2000. There was controversial talk of turning it into flats, but now it, too, is a private house – albeit one with an ancient medicinal well in the paddock out the back.

ONE of 2015’s many unfinished lines of inquiry concerned another ecclesiastical oddity. In Memories 240 back in July, we were telling of the A67 between High Coniscliffe and Piercebridge which was newly reopened after the landslip at Carlbury.

But what, asked Hugh Mortimer, was the churchy-looking stonework that peered over the top of the wall of Carlbury Hall.

Christine Port in Darlington responded immediately, pointing to a reference that said that this was a survivor from Neasham Abbey, which once stood on the other side of Darlington.

The abbey was founded beside the River Tees in 1203 by Lord Dacre, Baron of Greystock. It was dedicated the Virgin Mary and was home to eight Benedictine nuns. But they were naughty nuns – on one occasion they were admonished for their bad behaviour, and on another they were told off for pawning their altar cloths.

In 1534, Henry VIII dissolved the monasteries and three of his men pulled down Neasham Abbey, making the nuns homeless.

In the 17th Century, a house – now called “Neasham Abbey” at the western entrance to the village – was built on the site. There must have been bits of old stonework knocking about, because a carved piece of a 12th Century cross is now in the Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle, and, in 1875, when Darlington bank manager Thomas McLachlan was building his Scottish style mansion on the Carlbury cliff above the Tees, he managed to acquire the ruined archway to romantically beautify his garden.

Every motorist whizzing from Darlington to Barnard Castle along the relaid treetop road must have noticed it.

Many thanks to Christine for this nugget of information – and to everyone who has been in touch in 2015. Your contributions keep this supplement rolling along.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here