“PEOPLE think you just tip a load of tatties into a potato pie,” says Derrick Robinson, taking us back to one of our favourite topics. “No, no, no, no, no…”

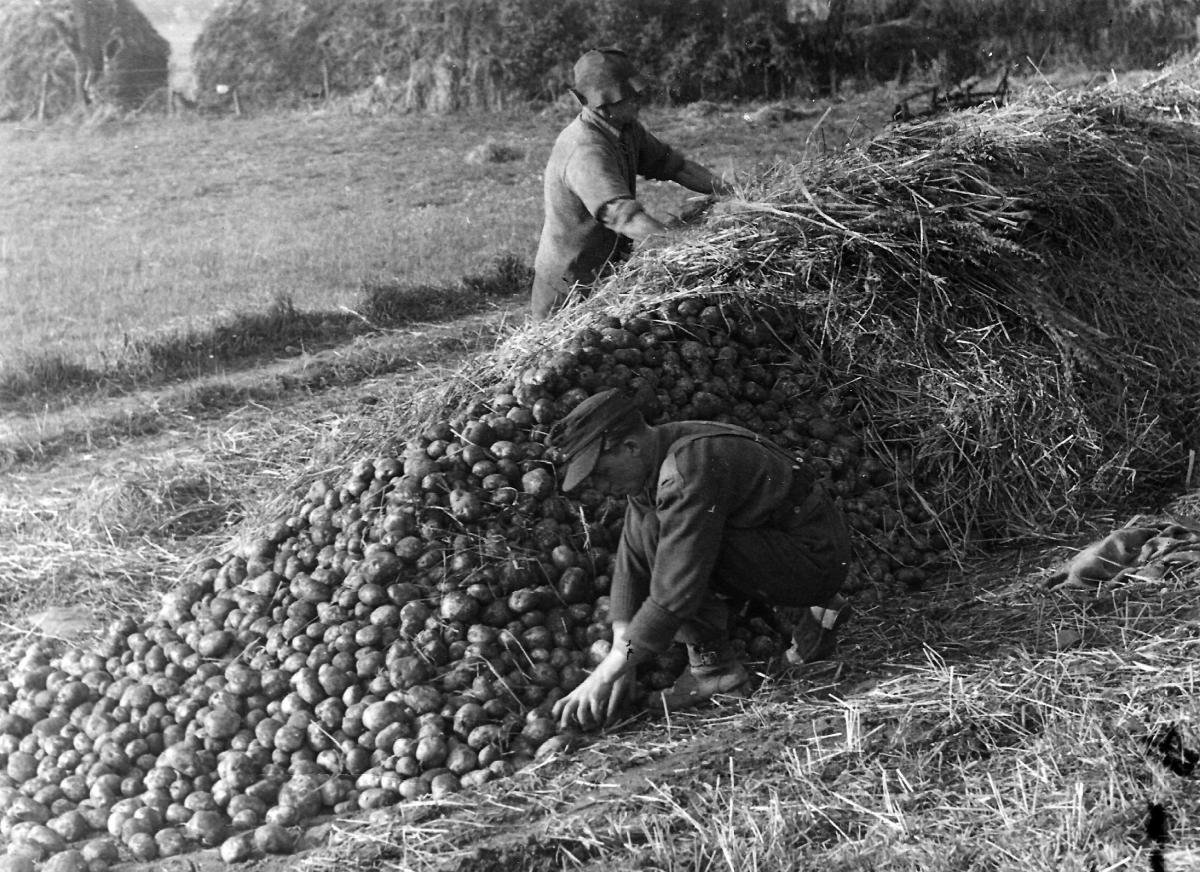

In the days before indoor storage, and before Smash, potatoes were stored in pies, or clamps, out in the fields. The spuds were heaped over with soil and straw which protected them from the elements, and rodents, until they were required at market.

We’ve already established that there was a real art to the construction of the potato pie, but now Derrick has been in touch to explain some of the science behind tatty growing.

Along with his brother Brian, Derrick has won more than 100 trophies for prize vegetables and flowers, but he started off on the family farm at Middleton Tyas in the late 1940s.

“To grow tatties, you would get your land spot on, row it up with a horse plough, get it level and soft,” he says. “Then Mayday comes when you put your cattle out which leaves your buildings empty but full of muck. You load your cart up and your horse takes it up to the tatty field and with your griper you pulled it off, and a gang of you do the spreading, making sure every bit of every row had got muck in.

“Then you get a hessian sack, tie each corner with string and put it over your neck, put your sett tatties in there: you put your right hand in the sack and put one in the row and then your left hand in and put another in the row and that’s how you would plant them.”

The potatoes grow over the summer until mid-October, when the back-breaking tatty picking season began.

“For tatty picking, you would spread your row with your rowing plough and then you’d get your tatty spinner, which would go underneath the row and spin the tatties out,” says Derrick, of Walkerville, near Catterick. “A tatty spinner was about 4ft high with loads of claws on it, and as you wheeled it up the rows it spun and kicked the tatties out, making it easy to pick them up.”

The picked potatoes were then separated by size and had the soil knocked off them by a riddle – a shaking device which allowed the smallest to fall through – until they were ready for the pie.

The pie started with bales of hay around the edges and cartloads of potatoes tipped in. The bales were teased away, and soil and wheatstraw was laid on the sides of the pyramid of potatoes to create the pie.

Then Derrick introduces a brand new word to explain how the pie was topped off: the wrigglewist (other spellings may well be available).

A wrigglewist was made from a baton of wheatstraw from the thrasher – and, as everyone surely knows, a baton is a 6ft tall sheaf held in place by two pieces of binder whereas a shav is just tied up with one.

“I never saw how a wrigglewist was made, but you get batons of wheatstraw and roll them together until they are four yards long, lay them at the top of the pie and shuffle them into place,” says Derrick.

Like thatch on a building, a wrigglewist kept the weather out.

Modern techniques have moved tatty picking into the 21st Century, but that doesn’t mean everything from the days of potato pies should be forgotten. A recent article about the perils of fluke worm in cattle in the D&S caused Derrick to remember when his family’s farm had a flock of Khaki Campbell ducks which picked the fields clean of the worms.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here