DR WHO writer Mark Gattiss, charged with bringing the Daleks to life for a new generation, is probably the most famous living person to hail from the south Durham village of Heighington.

The most famous dead person must be Captain William Pryce Cumby, the hero of Trafalgar, who will be remembered in an exhibition in the village on Saturday.

Capt Cumby’s mother, Eleanor Jepson, came from a long-standing village family. She married a naval lieutenant and gave birth to William in Dover on March 20, 1771. Sadly, she died 14 days later, so the baby was sent back to Heighington to be brought up by his aunt and uncle. They, in turn, sent him to school in Richmond.

When he was 11, William went to sea as an officer’s servant, and he began learning the nautical ropes and rising up through the ranks. On October 21, 1805, he was first lieutenant on HMS Bellerophon, a 74-gun ship of the line with a crew of 540, off Cape Trafalgar on the south-west coast of Spain.

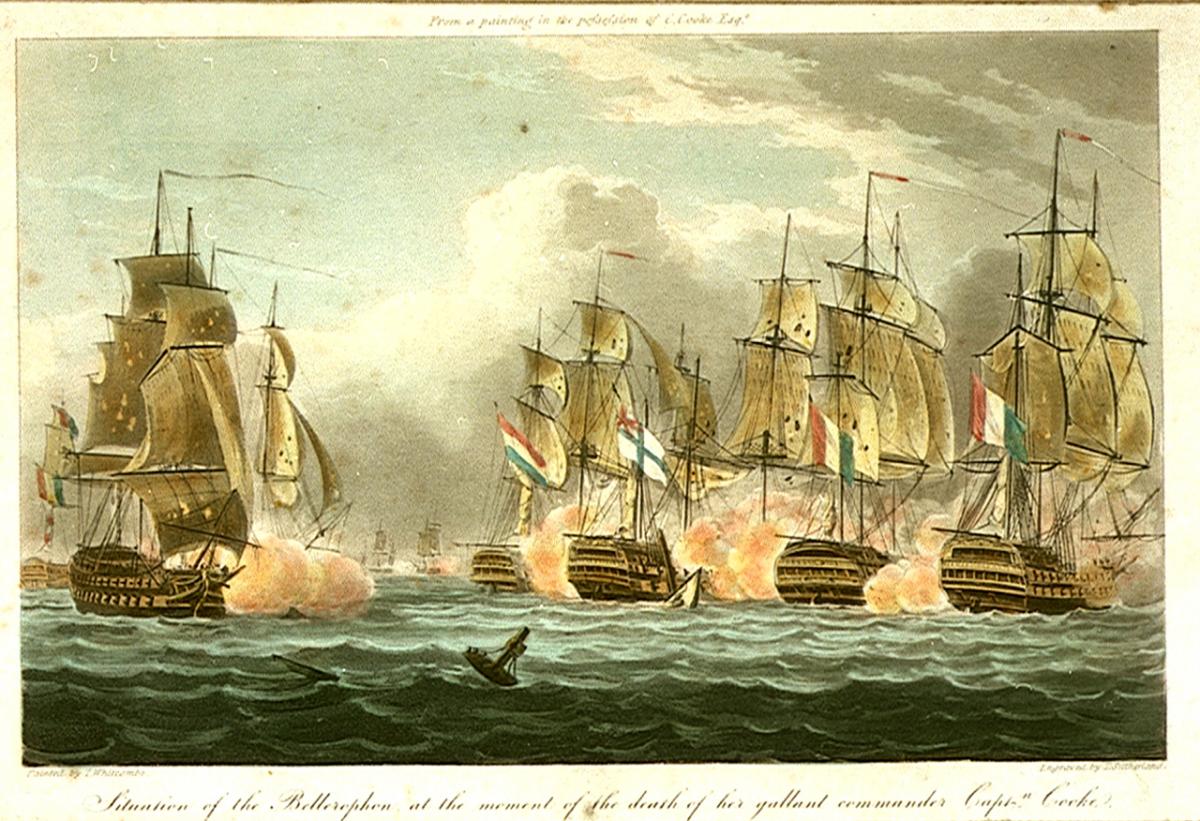

As the French and Spanish navies engaged with the British at about 11am. The Bellerophon was in the thickest of the fighting from the get-go – at 12.30, she fired deep into the Spanish vessel Monarca and then collided with the French warship Aigle. Close range fighting began, with Aigle assisted by three other warships, and just as Cumby advised Captain John Cooke to remove his stripes because the French gunmen appeared to be targeting officers, Cooke was killed by two musketballs to his chest.

Cumby was catapulted into command. The French were lobbing hand grenades onto his deck.

“Some of these exploded and dreadfully scorched several of our men,” he later told his son. “One of them I took up myself from the gangway where the fuse was burning and threw it overboard."

It was touch-and-go for half-an-hour, but Cumby managed to repel boarders, smashing the French hands as they clung onto Bellerophon’s rails, and at 1.40pm, Aigle retreated.

Although Trafalgar is remembered for the heroics of Admiral Horatio Nelson, Cumby had truly secured the British victory and, having captured two warships, he sailed Bellerophon home in triumph. He was promoted and given his own command. He sailed to the Americas to tackle the pirates, and privateers, of the Caribbean. On one raid, he rescued a cargo of black slaves.

In 1815, Cumby retired and in 1827, inherited the Old Hall in Heighington, where he lived, assisted by his servant, John Peters, who was one of those rescued slaves.

With his Trafalgar prize money, Cumby bought three local farms and, in 1833, built Heighington House (also known as Trafalgar House) which his descendants lived in until 1980.

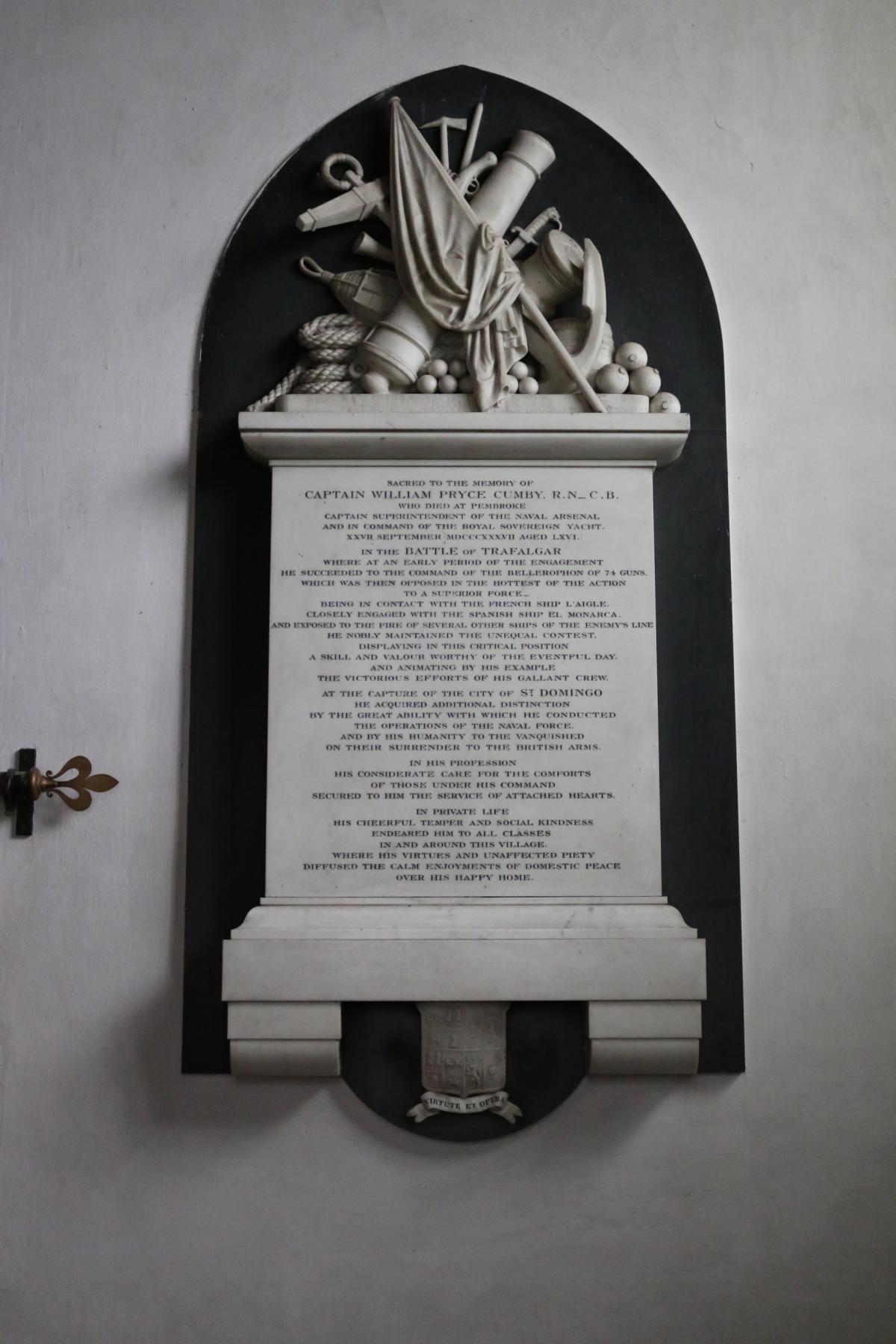

Cumby died in 1837 on board a ship at Pembroke Dock in Wales, where he is buried, but his officers collected money for a handsome memorial to him which is near the altar in Heighington church.

HEIGHINGTON SCOUTS have been challenged to bring together 100 people of all ages for an event, and so on Saturday, they are holding a history exhibition in their village hall. Captain Cumby will undoubtedly feature.

The village hall is itself historic as was effectively started in 1601 when Elizabeth Jenison, of Walworth Castle, set up a trust fund to pay £11-a-year for a grammar school to be established outside the west gate of the village church.

In 1788, the school was still thatched, and it might remain so to this day if it wasn’t for the Reverend Robert Blacklin. He became schoolmaster and curate in 1770, and from the 1780s, he allowed the school to go to rack and ruin, despite taking every penny due to him as schoolmaster.

He was sacked as curate, there was local outrage, his family deserted him, the Bishop of Durham descended in 1808 and demanded an improvement. But the school building fell down and still he took the money.

He only agreed to give up the post of schoolmaster, and the income that went with it, in 1829 when the charity commissioners offered him a lump sum of £100 and £20-a-year for life. As Sir Timothy Eden of West Auckland noted, it was a brazen – and successful – example of blackmail by the clergyman.

Villagers rebuilt their school, with a tiled roof, on the same spot and in the 1870s enlarged it further.

Older children were sent to Shildon in 1951 and it became a primary, and when it moved to its new premises in 1966, the old building in the shadow of the church tower became the village hall.

So there’s plenty of history to go at in Heighington – indeed, in 2006, a BBC4 programme fronted by historian Ptolemy Dean declared Heighington to be Britain’s most perfect village due to the combination of history, architecture and community.

The Scouts’ exhibition is opened on Saturday at midday, with a short talk by Chris Lloyd, who compiles these notes. It runs until 2pm, and there will be sandwiches, cakes and refreshments for sale, with money being raised for a defibrillator. Can we get 100 there so the Scouts fulfil their challenge?

From the Darlington & Stockton Times of April 26, 1919

LIFE – and beer – was getting back to normal after the First World War.

“Better beer in prospect” was a headline in the D&S Times 100 years ago this week.

“The beer known by the public and publicans as “Government ale” is shortly to disappear,” said the paper. Before the war, it said, the average gravity – an indicator of the beer’s strength – had been 1050.2 (in Ireland, where men really are men, it had been 1066.4).

However, wartime restrictions introduced in 1915 restricted it to a paltry 1032, but now in peacetime, the Government was going to allow it to rise to 1040.

“At 1040,” said the D&S, “brewers should be able to produce a palatable beverage.”

There was also an “Easter bicycle boom” as cycling returned to its pre-war popularity. “There is a tendency among men discharged from the forces to turn to this healthy and pleasant recreation.”

However, said the D&S, the roads were in a poor, dusty condition, and there was a shortage of bicycles. A new one could cost up to £20 – twice the price in 1914.

“The rarest of all accessories just now is the ordinary bell,” said the paper. “’There are no bicycle bells for sale anywhere in the country,’ said one cycle dealer, ‘because only one firm in England makes them. Formerly, Germany supplied most of our bicycle bells.’”

Beer and bikes aside, the war had had a profound effect on nearly everyone. The D&S reported how a ceremony had been held around the Market Cross in Northallerton to present former Sgt Thomas Wilbor, 30, of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry, with his Military Medal.

The ceremony had been arranged because “his comrades and friends in the district felt they should take this opportunity ofg expressing their regard and esteem for a man who had done so remarkably well for them”, said the D&S.

County Alderman John Hutton read out the citation: “At Champagne on the Marne, on April 23, 1918, during the German offensive, he took prisoner a Prussian Guardsman throwing bombs, although wearing a brassard as a Red Cross stretcher bearer.”

Thomas had grown up in Black Swan Yard in Northallerton and before the war had worked as a railway shunter in Middlesbrough. He was wounded at Ypres and hospitalised for three months; then he was wounded by shrapnel in the leg and eye and buried beneath tons of soil, and was hospitalised for a further month before returning to the front line to win his Military Medal.

He was one of five brothers who had served: Richard, 22, had been killed at Ypres with the Green Howards; Percy, 26, had his jaw broken by a bullet in France; Fred, 24, had been wounded three times with the Green Howards and was still suffering, while Arthur, 20, was still out with the Royal Navy.

ONE hundred years ago this week, the D&S Times recorded the death of Darlington’s first elected woman.

She was Clara Curtis Lucas, was born in Thirsk in 1853, the daughter of railwaymen. She was educated at Darlington’s Polam Hall School which, in those days, was a radically-minded hotbed of female equality. After leaving school, she ran nightclasses in a bid to spread educational opportunity, and she became a leading light in the women’s suffrage movement, touring the region and speaking out for her cause.

“She was an earnest and zealous advocate of ‘votes for women’, though not a militant suffragist,” said the D&S. “No one locally did more than Miss Lucas to secure the Parliamentary franchise for women.”

In 1894, Miss Lucas became the first woman in Darlington to be elected to office when she voted onto the Education Board which ran the town’s schools.

That was as far as she could go until August 1907 when the Qualification of Women Act enabled women ratepayers to be elected as councillors. She first stood in Cockerton in 1915, and came third in the poll, just winning a seat by 25 votes.

The mayor, Councillor JG Harbottle, “specially congratulated her as being one of the few women in England who was privileged to sit at the council table”, said the D&S.

However, such was the windbaggery of the 27 male councillors and aldermen during her first, lengthy, council meeting that she said at the end: “If we’re going to be here all this time every month, I’ll bring my knitting.”

She took her place on the education committee and was vice-chairman of the museum and library committee, although as the chairman was away on active service, she was effectively in charge.

Unfortunately, as peace came, Miss Lucas fell seriously ill, and was confined to the newly-built house – Fieldhead in Abbey Road – which she shared with her spinster sister, Alice. She appeared to recover, only to suffer heart failure at 12.30pm on April 14, 1919. She was 65.

The D&S said: “Miss Lucas was a pioneer in movements for the advancement of women politically and socially and she had the satisfaction of seeing the achievement in a certain measure, if not to the full, of some of the objects for which she had long and zealously striven, particularly in the extension of the Parliamentary franchise to members of her sex.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here