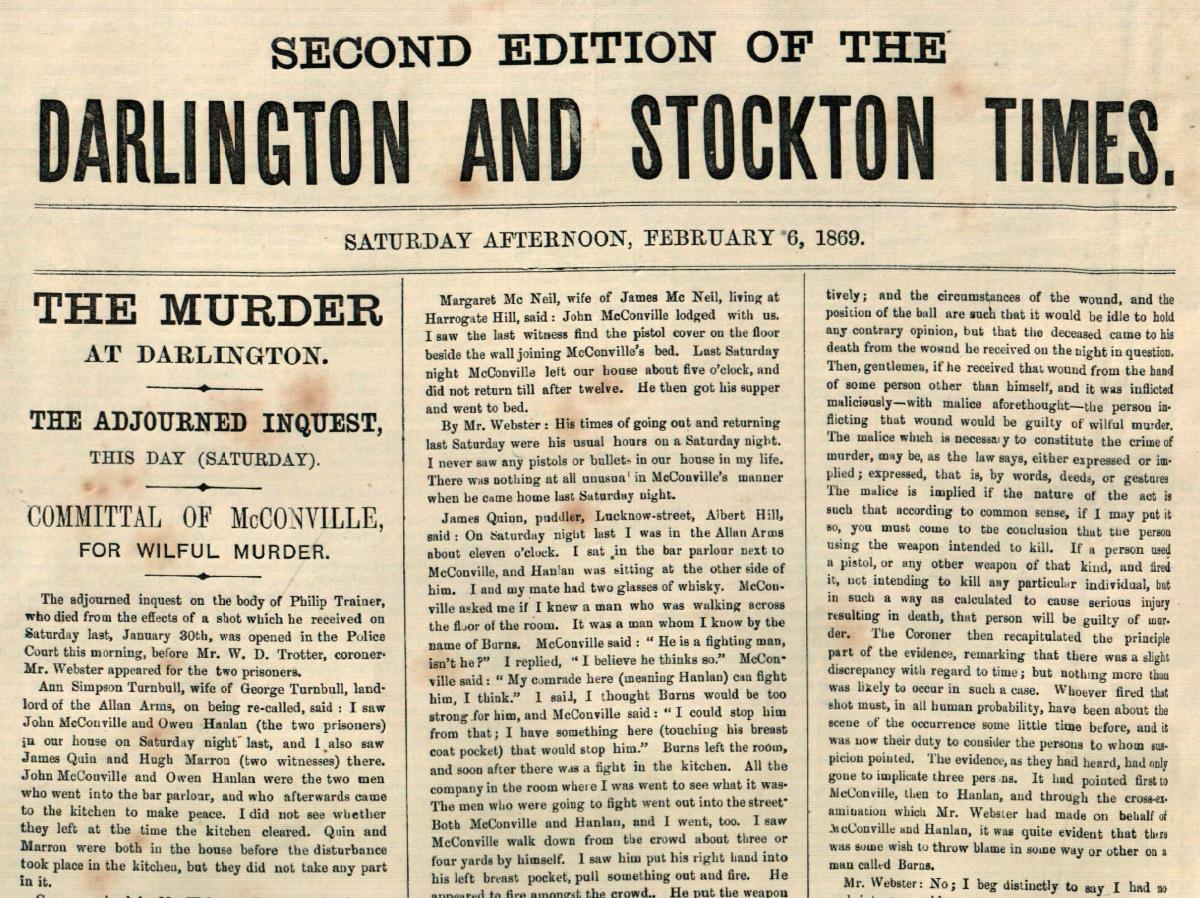

From the Darlington & Stockton Times of March 27, 1869

“THE morning was dull, and threatened rain, and the aspect of affairs about 7.30 was cold, cheerless and dreary,” reported the Darlington & Stockton Times of events at Durham jail 150 years ago this week. “At a few minutes to eight o’clock, the bell began to toll. The solemn sound, as it rose in the still morning air, was depressing and melancholy in the extreme.”

The morning of March 22, 1869, was to witness Durham’s first double execution. It was to be the first execution to be held in private, behind the tall jail walls rather than in the front of the courthouse before a crowd of thousands in Old Elvet.

And it was to be the first execution of a man who had committed murder using a firearm in County Durham.

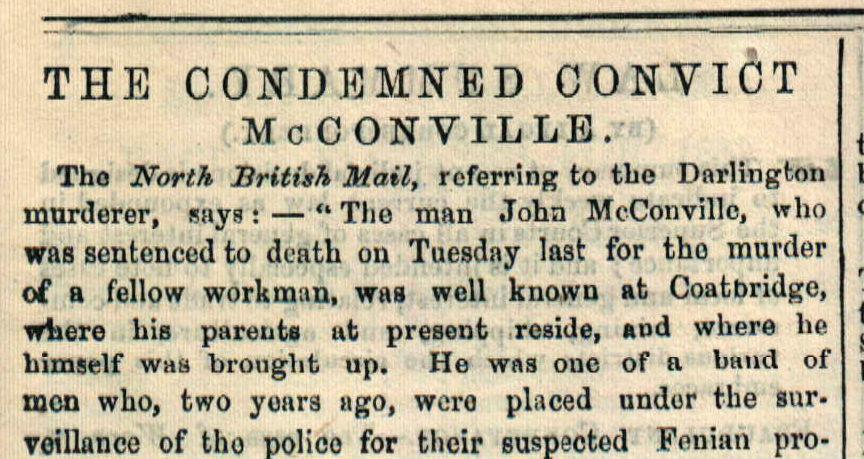

That murderer was “Gentleman John” McConville who, as recent Looking Backs have told, was found guilty of shooting a fellow Irish ironworker through the eye from point blank range in a melee outside the Allan Arms on Albert Hill in Darlington.

He was to hang alongside John Dolan who had got into a drunken argument with Hugh Ward over his treatment of their landlady, Catherine Keshan, in Union Lane, Sunderland. When the police had failed to intervene, Dolan had used a shoemaker’s knife to stab Ward in the bowels and the eye.

Although Dolan was also Irish, his was just a crime of alcohol-fuddled violence, whereas there was a fear that McConville, an intelligent, educated man of about 25, was involved in the Fenian Brotherhood which wished to overthrow the British government and set southern Ireland free. Indeed, since his trial, it had emerged that in 1867 McConville had been arrested in County Cork fighting for the Fenian army against the British, and he had been implicated in the “Manchester outrage” – 30 Fenians had attacked a police cart, killing a policeman but releasing their arrested leaders.

So great was the fear that since the McConville’s conviction, police had been guarding Durham jail in case the Fenians staged a jailbreak.

For the execution, said the D&S, the Durham authorities had engaged the City of London executioner, William Calcraft, but they were surprised the night before when he turned up on a train followed, a few hours later, by Thomas Askern. Askern was the York-based hangman who had performed the last execution at Durham, on March 16, 1865, when the rope around Gateshead wife-murderer Matthew Atkinson had snapped on the first drop. Atkinson had been revived with brandy and had spent an hour discussing his predicament with members of the large crowd until Askern had procured a thicker rope. After such a bodged operation, the Durham authorities had preferred the skills of the “grim finisher” Calcraft.

At shortly after 8am, the two convicts were led from the cells, accompanied by Catholic priests, past their own freshly-dug graves to the scaffold.

“McConville’s face was very pale, but his bearing was bold and erect, and his tread about as firm as on the day in which he appeared in the dock,” said the D&S.

“The convicts took their stand upon the drop. Calcraft immediately fastened the end of a rope to the crossbeam and slipped the noose at the other end of it over the head of McConville. The white cap was then drawn over his face.

“Both men prayed earnestly, and were attended to the last by their spiritual advisers.

“Everything being in readiness, a few minutes after eight o’clock, Sheriff Ranson, in accordance with previous arrangement, drew a pocket handkerchief out of his pocket. Calcraft, observing the signal, immediately drew the bolt, and the wretched culprits were launched into eternity.

“Dolan appeared to die very easily; in fact, beyond slight convulsive movements of the fingers and legs, no sign of life was visible after being thrown off.

“It was very different in the case of McConville. A tremendous struggle appeared to be taking place within him. His whole frame appeared to be convulsed, and his body occasionally was seen slightly to rise. During the time his fingers also moved convulsively, and it was not till 8.20 that the body became completely still.”

The bodies were cut down at 9am. The ropes and paraphernalia were burnt. Inquests were held at 11.30am, and the bodies were buried in the yard soon after.

The D&S was content that the private execution had prevented a grotesque spectacle where the thousands of watchers were usually stupefied by the majesty of the law and the amount of alcohol they had consumed.

“The only outward sign that such a thing had taken place was the hoisting of a black flag from the top of the prison,” said the paper.

A PETITION had been circulating in Richmond calling on the mayor to give everyone an extra day off on Easter Tuesday. The petition, said the D&S, had been “numerously signed by the tradesmen etc” who wished to give their employees another day’s holiday.

“His worship has complied with the requisition and has recommended that that day be observed in Richmond as a general holiday,” said the D&S.

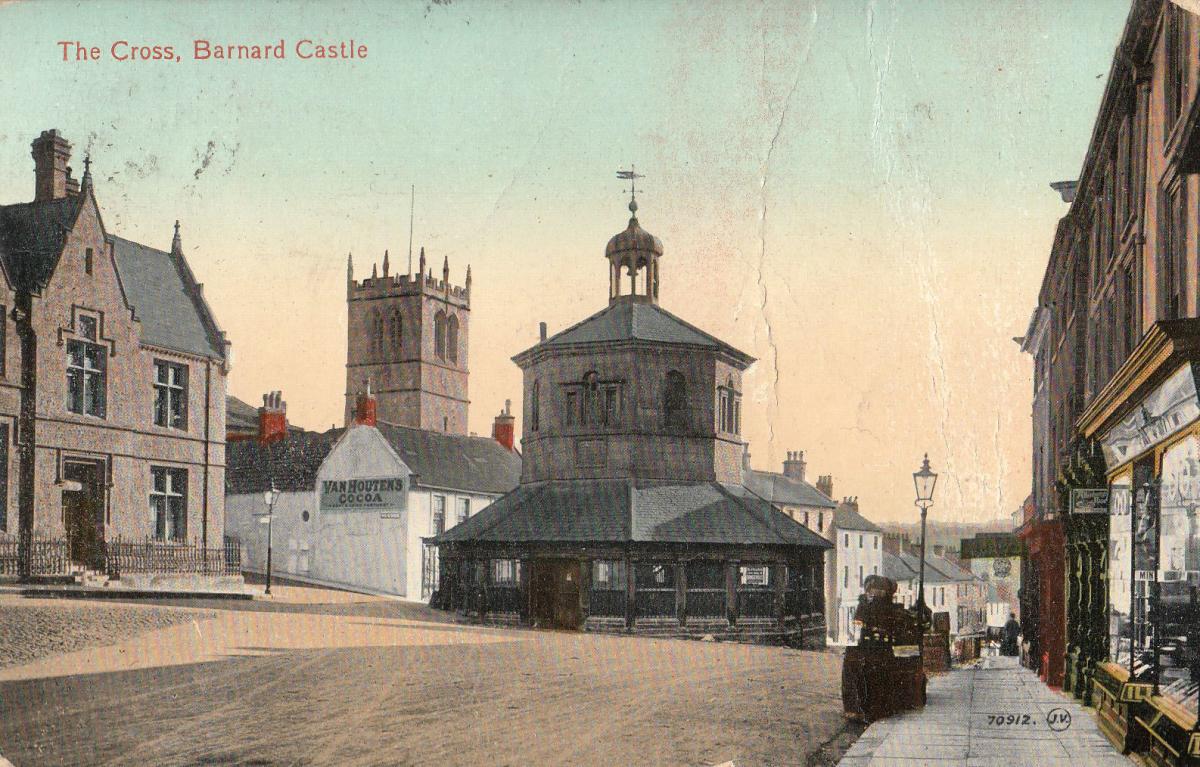

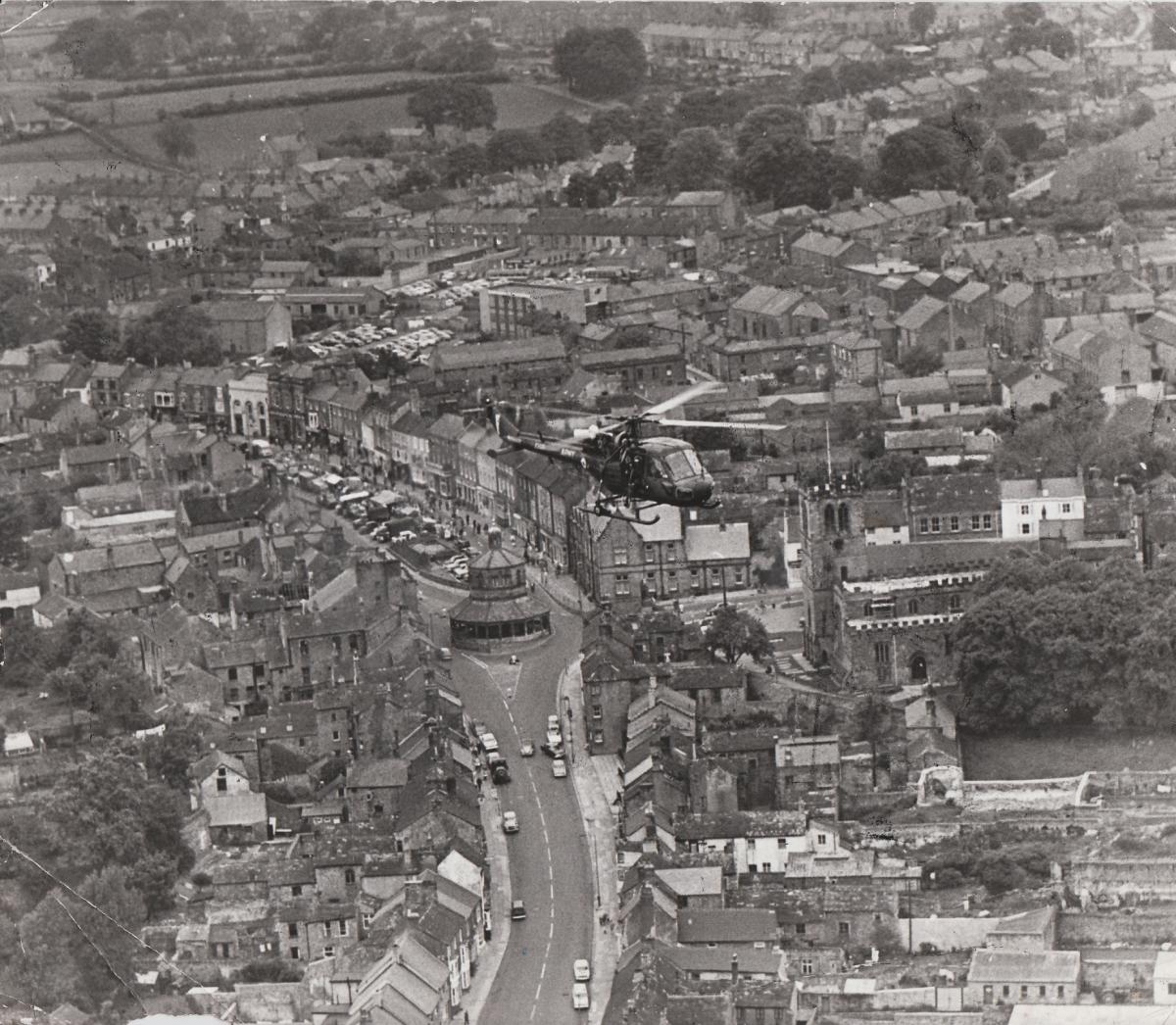

IN the church in Barnard Castle, the D&S reported that “the removing of the pews and galleries is now nearly completed and in a few days, the interior of the church will be clear of obstacles and the real work of restoration will begin”.

This was the commencement of probably the most important project in St Mary’s history. The church dates from 1130 and over the centuries it had grown in a quaint but higgledy-piggledy fashion with no one really bothering about maintenance.

In 1795, solicitor and writer William Hutchinson described the whole of the church as “slovenly and offensive”. As burials still took place inside, members of the congregation often found themselves standing on piles of earth with bones from a previous generation sticking out.

The restoration of 1868-1870 lowered the floor two feet to its original level, and took the huge and heavy raised pews, or galleries, off the walls.

“A great quantity of bones has been brought to light, which will be carefully re-interred,” said the D&S, “and the vaults exposed by the removal of the flooring will be properly re-covered.

“On taking down the old gallery, it was found that the structure must long have been in a very unsafe state, and might have fallen under a very little more weight than it usually supported.”

The 14th Century was found to be in an even worse state. It was so dangerous that it could collapse at during the next bell ringing session. So the bells fell silent, and the congregation had to raise more money to rebuild their tower.

But 150 years ago they were clearly undimmed by the work ahead. They met in large numbers in the music hall. “We never remember the singing to have been better than on Sunday,” said the D&S, “and the congregation are highly indebted to those ladies and gentlemen who have so kindly volunteered their valuable assistance in the choir.”

March 29, 1919

THE Spectator column was hoping that peace day – the day the treaty formally ending the First World War was due to be signed – would be commemorated across the country by a chain of beacons, or “twinkling points of fire”. Queen Victoria’s two jubilees, in 1887 and 1897, and King Edward VII’s coronation in 1902, had been celebrated in such a way.

“In this connection, it is recalled that the Hambleton Hills were an important factor, commanding the vales of Mowbray and York to the west and south, and a wide district stretching to the Wolds on the east and south-east, the outer eminences of this plateau offer many ideal sites for beacon fires,” said Spectator.

He concluded that “the rugged face, 950ft above sea level” of Roulston Scar, from which the gliders fly above the White Horse of Kilburn, was the best location, and he quoted John Sanders, of Cold Kirby, who had been there in 1897 when it was the scene of “the biggest blaze in the north”.

“A cross trench was dug and sticks were piled round a fir tree placed upright and 30 or more feet high,” explained Mr Sanders. “We could see from our site the fires lit to the south-east, the south, and away west to Westmorland. Crayke gave a big blaze, next to our own the finest we saw from here.

“At the 1887 Jubilee, they made a fire on Roseberry Topping, which burnt for over a week – but a big blaze for a couple of hours is the more effective display.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here