From the Darlington & Stockton Times of March 20, 1869

EXTRAORDINARY goings-on at Guisborough 150 years ago where John Robert Thorley, 47, and Walter Thomas Grinyer, 21, were charged with obtaining five shillings by false pretences from James Merryweather in the town.

It was a specimen charge as the prosecution alleged that the pair had been extorting up to £8-a-week out of the people of the Guisborough in recent months.

Mr Thorley was the London-based brains of the National Income Tax Repeal Association and, said the D&S Times, “the prisoners had canvassed the country for the purpose of obtaining signatures to a petition and collecting subscriptions in support of the objects of the association”.

Income tax was introduced in 1799 by William Pitt the Younger to pay for the Napoleonic Wars. It was removed after the peace of 1815 as it was widely regarded as “repugnant” because it was so intrusive into the private lives, and earnings, of the British people.

However, Sir Robert Peel had reintroduced it as a temporary measure in 1842 – 7d in the pound on incomes over £150 – but the cost of the Crimean War in the 1850s had caused it to become permanent.

The debate at the York Assizes was about how genuine the association was. The prosecutor labelled it “a mythical association”, and said that Mr Thorley had been arrested in a “miserable room” in Raquet Court (an ideal location for a racket, but a real address in the 19th Century, at the end of Fleet Street) in London surrounded by petitions against income tax.

It was also said that he surrounded himself with shadowy people, including TH Ghisnin whom the D&S described as a “patentee of a plan for the utilisation of the use of sea-weed”

George Whalley, the MP for Peterborough, claimed he had not given the association permission to use his name on its literature, but he testified that he had recently presented 27 petitions from Mr Thorley to the House of Commons containing names of people who wanted to see the tax scrapped.

Mr Thorley’s barrister, Mr J Smith, defended him by saying that “the presentation of petitions showed it was not a sham and that it had done good work during its existence. The prisoner’s intention had been that of a respectable and intelligent man”.

The D&S said: “Mr Smith’s speech was a forcible one, and was applauded at its close.”

Mr Grinyer, who was the gopher going round the country collecting the money (he reported that the anti-tax message had been enthusiastically received by landowners in the Guisborough area), was let off.

But, after overnight consideration, Mr Thorley was found guilty. He sobbed in the dock, saying he hadn't meant to overstep the mark. The judge accepted that he was genuinely trying to drum up support in Parliament to abolish income tax, and so jailed for only four months.

GEORGE JACKSON was seen returning to his home of Tanton Hall, near Stokesley, “at a rapid pace on a spirited horse” from a sale of bulls in Stokesley, according to the D&S of 150 years ago.

“Turning the angle at the Tanton bridge, the horse fell and the unfortunate young gentleman was thrown off,” said the paper.

Mr Jackson suffered such a severe head injury that even though he was carried into the nearby hall, he died at 2am.

The inquest, in Stokesley, returned a verdict that he had been accidentally killed, and the D&S report concluded: “The jury wished the attention of the proper authorities to be called to Tanton bridge, which is a very awkward one.”

The 18th Century Tanton bridge is still a very awkward one. It carries the B1365 from Stokesley into Coulby Newham over the River Tame through a very tight S-bend. Its stone parapets bear multi-coloured testimony to the many other people who, like Mr Jackson, have come to grief on its turns.

But, 150 years later, help is at hand. In August, North Yorkshire County Council announced it was going to spend £500,000 widening “the bridge of scrapes”, with work due to start *****. The Looking Back column will, therefore, be taking its life into its own hands when it travels over Tanton bridge on Monday to talk to the Stokesley Society in the Town Hall. The subject is Of Fish and Actors: 100 Years of Darlington Hippodrome. The talk starts at 7.30pm and all are welcome – should we make it safely.

March 22, 1919

ONE hundred years ago this week, the area was in mourning for a lady “famous for her beauty”.

She was Theresa Susey Helen “Nellie” Londonderry, the dowager 6th marchioness, who had died in London of pneumonia.

The Londonderrys were spectacularly wealthy, and owned halls at Wynyard, Seaham and Mount Stewart in Northern Ireland. Nellie, said the D&S Times, “regarded Wynyard as peculiarly her home. There she and Lord Londonderry used to spend most of the autumn and early winter.”

Indeed, she is remembered at Wynyard as being a great gardener, and her legacy in that respect survives.

Said the D&S: “In Durham were the collieries which made the family wealthy, and there Lady Londonderry was the centre of a vast system of charitable, educational and ecclesiastical effort – much of it involving troublesome personal attention.”

Her husband, who died at Wynyard in 1915, had been a Conservative Unionist politician and member of the government, with her ladyship providing spectacular hospitality – their London home, in Carlton House Terrace, was the social centre of the Conservative Party.

Despite being such an immense establishment figure, Nellie was not without scandal. She had an affair with another Conservative MP, Harry Cust, and when another of his lovers came across her passionate love letters to him, she jealously delivered them to Lord Londonderry.

The marquess and the marchioness seem not to have spoken in private for some years because of this, so quite what Lord Londonderry made of it when she delivered a son, Reginald, in 1879, can only be left to the imagination. Reginald’s father was probably Nellie’s brother-in-law, although as the boy’s name was shortened to Rex, there was an even more scandalous rumour that Edward VII was really his father. When Reginald/Rex died aged 19, his mother created a rose garden in his memory at Wynyard, which is still there.

By the end of their lives, though, Lord and Lady Londonderry were a close and tender couple.

“The passing of such a social and political and philanthropic force will be widely felt, and her death has come at an age when many years of activity might have been expected for her vigorous spirit,” said the D&S. She was 63, and was buried in the family vault at Longnewton church – recent Looking Backs have told how, three generations earlier, the black sheep of the family, Lord Ernest had been buried at Thorpe Thewles church.

Queen Alexandra, the widow of Edward VII, sent a wreath of lilies, and there is an interesting line in the D&S’ report telling how the 7th marchioness had placed a wreath on the coffin saying: “To my darling second mother, from her daughter-in-law, in ever loving remembrance. Till we meet again.”

The 7th marchioness was Edith, who had married Nellie’s eldest son, and she had a scandal, too. On honeymoon in the “gay Nineties” in China, she had had a couple of tattoos inked on her legs. On one, was an ankle to thigh “rampant British lion…in tea rose pink” and on the other was “a baby blue coat of arms and a star, just above a strikingly life-like green garter snake”.

The fashion for long skirts kept such unladylike adornments well out of sight, although during the 1930s, when hemlines rose, London society was shocked to discover that such a bastion of the establishment as the Marchioness of Londonderry was a painted lady.

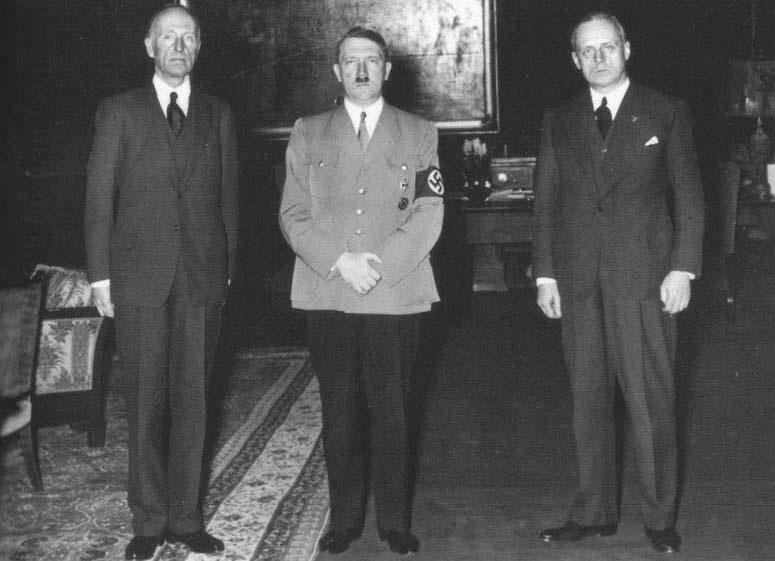

However, Edith’s scandal faded into insignificance compared to her husband’s carrying on. The 7th marquess had risen to become the Secretary of State for Air but, having experienced the horrors of the trenches in the First World War, he tried to closen Britain’s relationship to Nazi Germany. He visited Hitler in Berlin and, over a week in November 1936, he entertained Joachim von Ribbentrop, who would become Hitler’s Foreign Minister, at Wynyard.

IN BEDALE, the D&S reported 100 years ago this week how two families of Belgian refugees were saying farewell to the town which had given them shelter in November 1914.

The families, comprising 14 people, were among the 250,000 refugees that Britain took in when the Germans invaded their country at the start of the war.

At a ceremony at Bedale Town Hall, the rector, the Reverend William Beresford-Peirse, spoke of his regret at saying farewell but of his happiness that they were able to return to their homeland.

Eugene Van Ouytzel, an architect from Liege, “voiced the thanks and appreciation of the Belgian refugees for the hospitality and kindness received from the people of Bedale which, he said, would never fade from their memory”.

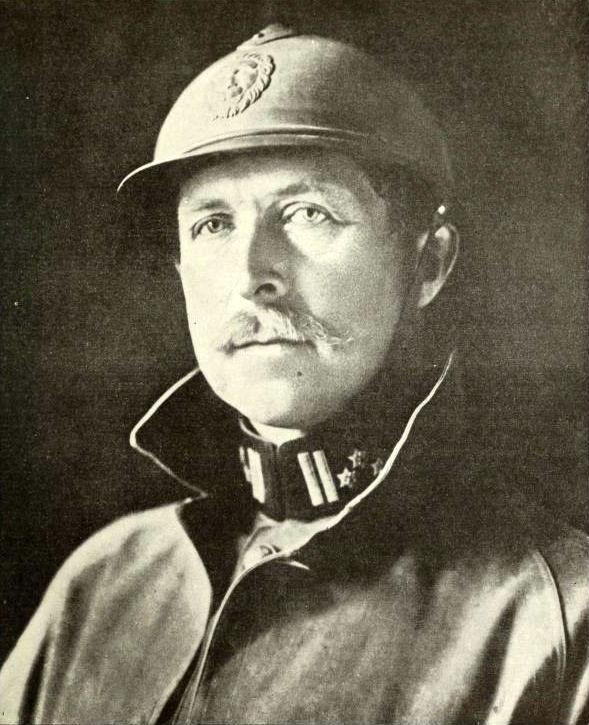

He presented an illuminated address as “a memorial of their gratitude”, which he had created by himself, and an enlarged photo of the king of the Belgians, to be hung in the town hall.

The D&S said: “The refugees left Bedale yesterday morning, and there was a good company to bid them farewell for during the last four years they have wound themselves around the hearts of many and had many close friends.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here