December 14, 1968

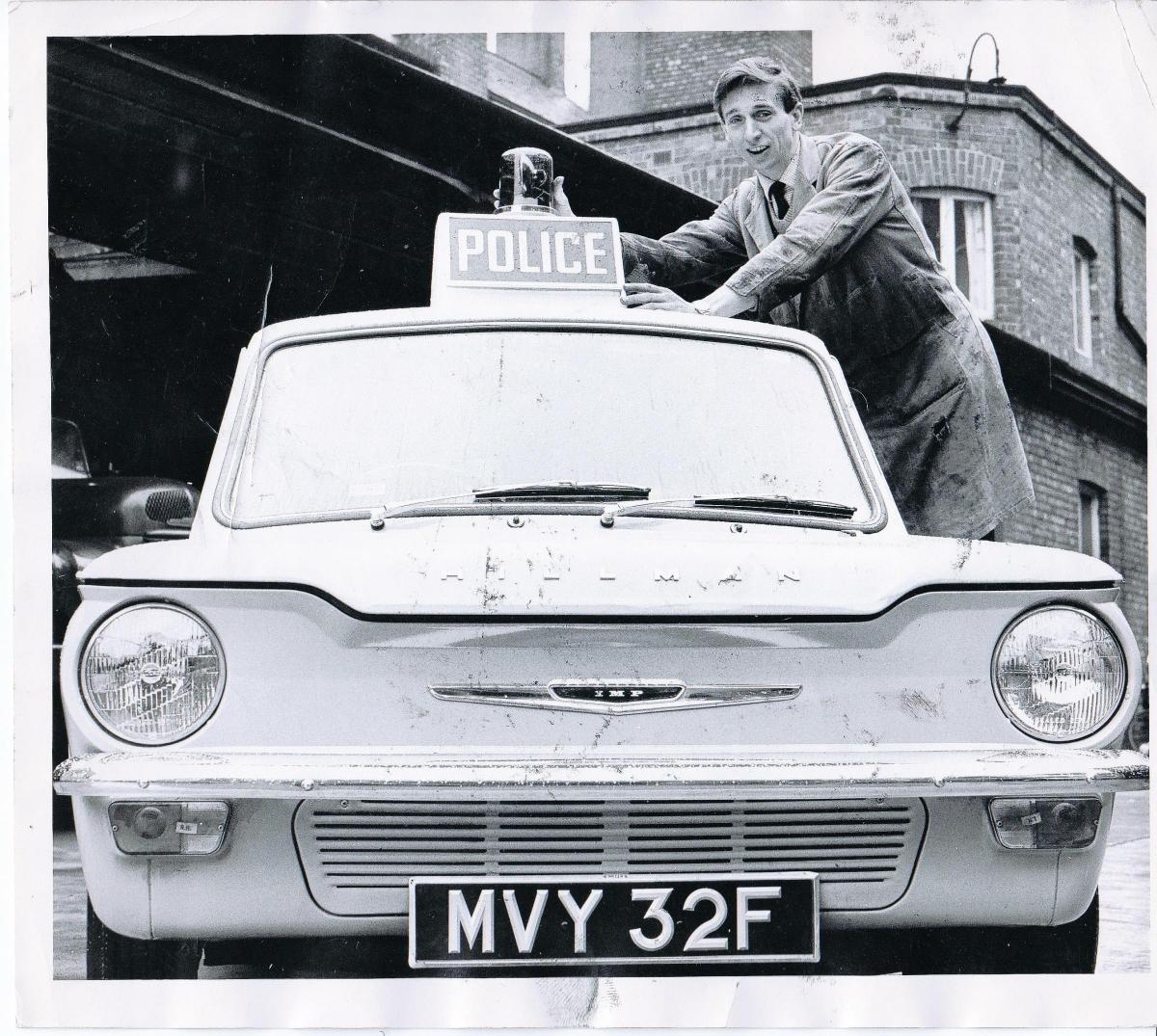

THERE was a disturbing headline for anyone not aware of the latest hip terminology 50 years ago this week. “Police pandas in the North Riding” it said, and rather than black-and-white bamboo-eating monsters being let loose, the Richmond and Northallerton area was taking delivery of the first of its 17 blue-and-white panda cars.

The panda car took the beat bobbies – they used to patrol in pairs – off their feet or bicycles and squeezed them into small Hilman Imps.

“The driver keeps in touch with headquarters through his own personal radio,” said the D&S. “A panda and its crew can be on the scene of a crime or emergency in less time than it took an old-style village policeman to find his bicycle clips.”

The motorised policeman had been trialled in Lancashire in 1965, and quickly spread across the country.

“The public have taken to the new system well,” said Ch Supt E Field of Northallerton Road Traffic HQ. “The cars are prominently marked so that we hope people will not hesitate to stop them if they feel they want to speak to the policeman as they used when they saw the village policeman on his beat.”

The obvious question here is why is a blue-and-white car named after a black-and-white animal. The Oxford English Dictionary notes that the word came into use in 1966, but even it can’t explain its derivation. The best guess, apparently, is that TV viewers saw these exciting vehicles on the first cop shows, like Z Cars, and as everyone had black-and-white sets, the little cars were called pandas. Can this be true?

December 14, 1918

THE D&S claimed 100 years ago that the influenza epidemic was abating, but then it told this story: “Influenza is still rife in Ripon, and four members of one family have fallen victims to the disease in the past fortnight.

“On November 30, Mrs Wright, wife of Mr Matthew Wright, maltster, residing at Magdalen’s Row, died of pneumonia following influenza. On December 7, a son and daughter, aged respectively 14 and 17, died of the same disease, and last Monday, the father himself succumbed.

“All the public elementary schools in the city and rural area have been closed until January 7.”

December 12, 1868

THE D&S reported exactly 150 years ago the outcome of a court case in which farmer Sarah Highmore was suing the North Eastern Railway Company for £17, the value of a cow which was killed on the Stainmore line between Barnard Castle and Bowes.

Ms Highmore’s barrister explained to the judge at Barnard Castle County Court that her farm near Bowes was divided in two by the railway and “the cattle had to be driven over the line at a level crossing for water”.

A train was due at 5pm, but as the hind arrived at 5.20pm and found the line clear, he presumed it had already passed and so started to drive the cattle across.

“It was not till one of the animals was upon the line that the train was seen to be coming round the sharp curve from Barnard Castle,” said the D&S. “The driver blew his whistle, but before the cow got across it was knocked down by the engine and killed.

“His Honour, having heard the evidence, said it appeared to him that there was negligence on the part of the company. The whistle had not been sounded before rounding the curve, neither had the speed of the engine been lessened. No caution had been observed, although the train was 20 minutes behind time.”

Ms Highmore was awarded the full £17, plus costs.

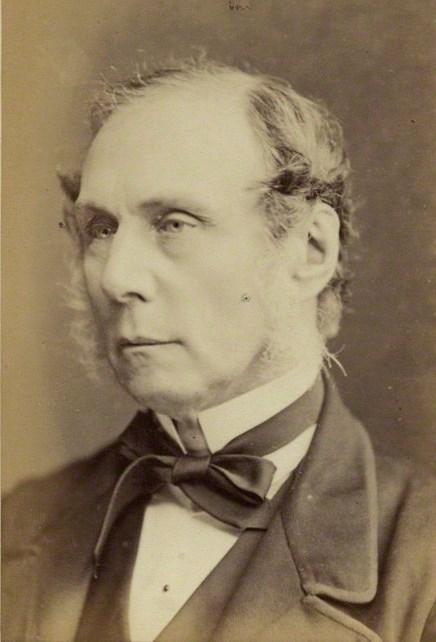

The D&S also published a paean of praise for Sir Roundell Palmer, who had been the Richmond MP since 1861. A deeply religious barrister, he had been Attorney-General, but when Prime Minister WE Gladstone offered him greater office, as Lord Chancellor, with a peerage attached, he refused because he wanted to keep his backbench seat and fight Gladstone’s attempt to disestablish the church in Ireland (as the Protestant church was the state church, every Irishman had to pay a tithe to it, even though most of them were Catholic and worshipped elsewhere, causing great grievance).

The D&S was deeply impressed. “No living man has made such a sacrifice of ambition to principle as Sir Roundell Palmer,” it said approvingly, “and no honour the country may bestow upon him can be too great.”

Sir Roundell didn’t have to wait too long. Less than four years later, he became Lord Chancellor and was created Baron Selborne.

Hidden in Full View: A History of the Chief Justice of Carolina’s Mansion House in Sedgefield by Ean Parsons (£12.99)

THE Manor House in Sedgefield is a remarkably large and grand house overlooking the green which is rather overlooked because it is no longer centre of the village's attention.

Its past has previously been elusive, even though it has a couple of lovely eye-catching details: there's a mind-bogglingly complicated sundial above the main door and a pair of pineapples on the gateposts.

The sundial, dated 1707, is so complicated because the building faces east and so the sun's rays require some interrogation before the time can be told.

The pineapples are special because 200 years ago, they represented the height of luxury and extravagance. The pineapple comes from South America – where its name "ananas" in the Tupi language means "excellent fruit" – and would only grow in the hottest of British hothouses. Therefore, only the wealthiest people could offer their guests a taste of its stunningly sugar-sweet flesh. Indeed, rich people used to hire pineapples to grace their table, but because the fruit was so rare, the guests couldn't eat it as the pineapple had to travel on to its next engagement enlivening another nobleman's table.

But beyond that, we struggled to find out more about the Manor House.

In 2014, the author of the new book became the owner of the house, having rented offices on its upper floor since 2000, and intrigued by its blank canvas, he set out to find out more.

The results of his researches now fill the 156-page and tell a great story.

He believes the house was built by Robert Wright, who was the North of England Judge of the Common Pleas in the late 17th Century. He was from East Anglia, and was the son of an eminent judge, Sir Robert, who became James II’s Chief Justice. However, Sir Robert fell dramatically from grace and died in 1689 in prison in London charged with high treason.

Young Robert, therefore, had little future in London and so came north to re-establish himself. Part of that re-establishment was finding a suitable wife, and although he was 23, he quickly married a 46-year-old Sedgefield widow, Alicea, from a well-to-do local family.

It was probably on a prominent, raised plot of her land that he built his grand manor house, in rare and ostentatious red brick, with a sweeping view over the green straight at St Edmund’s Church. He completed it in 1707 by placing the sundial on its frontage – a statement of his arrival, and the pineapples on the gateposts hinted at the luxuries his important guests would find inside.

But this respectable northern judge was living a double life, for in Bloomsbury in London, he had a mistress, Isabella, and seven children.

In 1723, Alicea died aged 80 and was buried in Sedgefield. Finally freed, a week later, Robert married Isabella in London and then took her, with their seven kids, their servants and his favourite coach, to America, where he became Chief Justice of Carolina and a plantation owner.

He put his former life, wife, and manor house, in Sedgefield way behind him – although, intriguingly, there are parts of Carolina called Sedgefield. In South Carolina, there is a Sedgefield plantation near Goose Creek in which there is a Sedgefield school, and nearby at North Myrtle Beach there is a development of condominiums called Sedgefield.

Back in Sedgefield, County Durham, without Robert, the manor house lost the reason for its prominence, and was gradually relegated and occasionally fell derelict. In 1799, it lost his command of the green when The Square was built in the middle of the grass, blocking its views to the church.

In the 20th Century, it became the offices of the rural district council and then a magistrates court, before again falling into disuse. Now it has been resurrected as a business centre and events venue which, after all these years, has been found to have an amazing back story.

Ean’s book is available by calling 07771 828 568 or email ean@manorhousesedgefield.co.uk

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here