As the centenary of women's suffrage is commemorated, Chris Lloyd tells of an early radical campaigner who is remembered in Scotland but overlooked in her hometown

WHEN Darlington’s Mechanics Institute celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1925, member Joseph Bowker raised a glass and proposed a toast, saying that the institute’s chief attraction was that it was without three things: no women, no drink and no gambling.

As he spoke, it may have been possible to hear the most important person in the institute’s history – a feisty female – spinning in her grave.

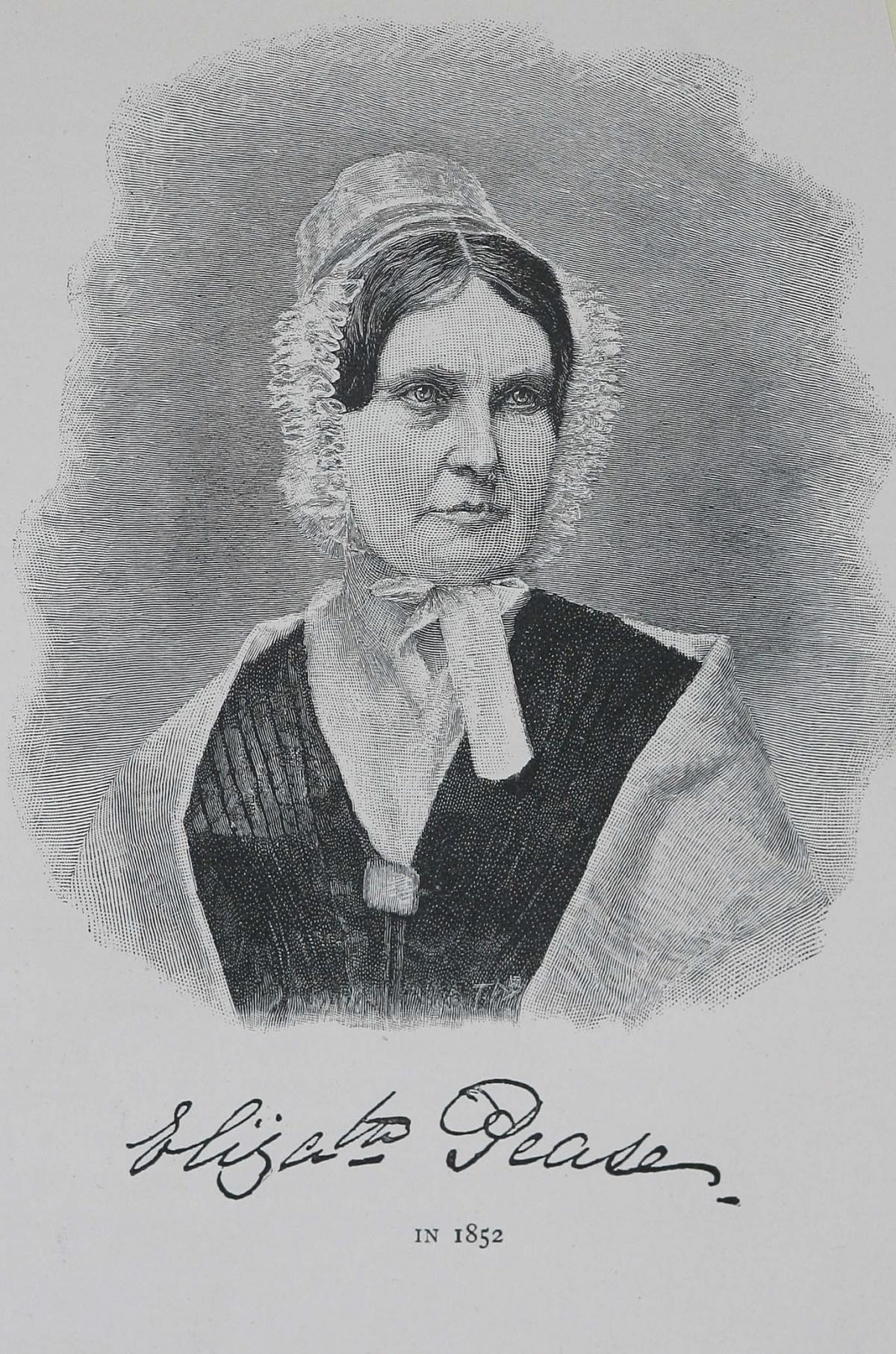

She was Elizabeth Pease, and not only was she interested in equality of educational opportunities across the classes in her hometown, but she was also interested in equality of voting opportunities for everyone – so much so that the city where she made her life after being expelled from the Darlington Quaker circle has been discussing whether, in this year commemorating the 100th anniversary of the first women getting the vote, to erect a statue in her honour.

Elizabeth was born in 1807 in Feethams, the grandest mansion in Darlington which stood where the Town Hall is today. She was a cousin of the railway Peases, and she was fired by unfairness. She believed that all men were equal, irrespective of the colour of their skin, and campaigned vigorously against slavery.

In June 1840, she attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London and was horrified to discover that women were not only forbidden from speaking but also had to be fenced off behind a bar and curtains.

This unfairness fired her further, and she became a “moral force Chartist”. The ruling elite of the 1840s regarded Chartists as revolutionaries – even though today, all but one of their six campaigning points are crucial to our constitution – but Elizabeth invited them to Feethams because they supported “the equality of women’s rights”.

She distributed Chartist literature; she supported workers striking in the factories of Yorkshire and Lancashire – even though her family owned the biggest factories in Durham. She didn’t, though, support the use of physical force in the battle for equality.

It is against this backdrop that in 1853, she gave the largest donation – £400 (about £50,000 in today’s values) – for the building of the £2,300 Mechanics’ Institute in Skinnergate.

The institute had been formed in 1825, in the earliest days of a worldwide movement to provide educational opportunities for the working class. The first mechanics’ institute in England had opened in July 1823, so Darlington’s was a trailblazer.

Yet it failed to take long-term root, and had to be reinvigorated in the 1840s to provide a library, lectures and classes as well as social facilities for its members. As it grew, it needed its own premises, and as the biggest donor, Elizabeth was asked to lay the foundation stone on May 12, 1853. She used a “silver trowel which was judiciously contrived to serve as a fish slice and was presented to the lady”.

Three weeks later, Elizabeth, 46, married Dr John Pringle Nichol in an independent chapel off Northgate. Dr Nichol was the professor of astronomy at Glasgow University and was considered to be the greatest astronomer of his day with an ability to fire the interest of the ordinary person in the heavens – he was the Brian Cox of his day.

But things did not get better for Elizabeth because Dr Nichol was a Presbyterian, and it was forbidden for a Quaker to marry outside her faith. Edward “Father of the Railways” Pease wrote that this was “a union very much advised against and disapproved by all her friends”.

And so because of love, Elizabeth was “disowned” by the Darlington Quakers and lived out the rest of her days in Scotland. In fact, her last visit to her hometown seems to have been on September 1, 1854, when she returned with Dr Nichol to perform the official opening of the Mechanics Institute. Her cousin, Henry Pease, chaired an elaborate tea for 500 people and her husband gave the well received inaugural lecture, entitled The Immensity and Endurance of Creation.

Elizabeth, as a woman, was not invited to speak, although she may have got the consolation of usefully wielding her fish slice.

Her husband lived just five years after their marriage – “Alas! Alas! Widow and desolate,” she wrote in her diary – and in widowhood she threw herself into numerous causes in her new home city of Edinburgh: peace, temperance, anti-vivisection and women’s suffrage.

She was a founder of the Edinburgh Women’s Suffrage Society in 1867; she attended the Great Demonstration of Women in Manchester in 1880 with 5,000 other women; she signed a “letter from the ladies” to MPs in 1884 asking for women who headed households to get the vote. For these efforts, Edinburgh, where she died in 1890, has been considering if she should be memorialised as part of its commemorations of the centenary of women getting the vote.

Darlington, of course, already has a memorial to her belief in equality: the grand Mechanics Institute building in Skinnergate, which is now a restaurant and nightclub.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here