Jan Hunter reports on the effect the First World War had on one North Yorkshire town

THIS year’s period of remembrance is all the more poignant because the sacrifices of the young men on the Somme 100 years ago will be uppermost in people’s minds.

July 1, 1916, was the first day of the battle, and is the blackest day in the history of the British Army – there were 60,000 casualties with nearly 20,000 young men slaughtered, mostly in the first hour of the first day.

Brothers, cousins and friends died beside each other.

The British had bombarded the German trenches for seven days before July 1, and the generals told their men: “You won’t find a rat alive in there now.”

But the German dug defences were lined with concrete, and set in the high ground, so where their soldiers sat the bombardment out.

When the British went over the top, the German guns, set to maim below the waist, cut down the young men like swathes of corn.

No town in the country was unaffected.

During the First World War, 300 young men from Stokesley enlisted to fight, and 54 were killed – although the numbers of the fallen differ on the memorials around the town. The one on West Green has 43 names, the Stokesley Parish Book of Remembrance has 54 names and the plaque on the south nave wall of the parish church has 51.

Indeed, in February 2016, another name was added to the number, when a bronze plaque, issued to the next of kin, was discovered. Research revealed that Rifleman Thomas Elstob, who was born in Middlesbrough in 1886, moved in the years immediately before the war with his mother to Stokesley. They lived in Oakland Terrace, and he enlisted for the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in Stokesley, and it was to Stokesley that the grim news was sent on December 1, 1915, when he was killed by a sniper in Belgium.

At the start of the war, the young men of Stokesley, like Rn Elstob, were eager to sign up. Kitchener’s recruitment poster was everywhere with the pointing finger and commanding words “Your Country Needs You”, and patriotic fever was sweeping the country. Another draw was that a soldier’s pay was higher than the wages paid in an agricultural community, like Stokesley.

Some were too eager to join up. Arthur Shore, 17, a member of the church choir, tried to enlist in Stokesley but was told he was too young. Having older brothers already in uniform he wanted to join up, even though his brother, William had been killed. He then tried to enlist in Middlesbrough and was successful, and was sent to France in June 1916. He was part of the attacking forces on the first day of the Somme Offensive and was killed in the first hour. He was awarded the British War Medal and Victory Medal and has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing of the Somme.

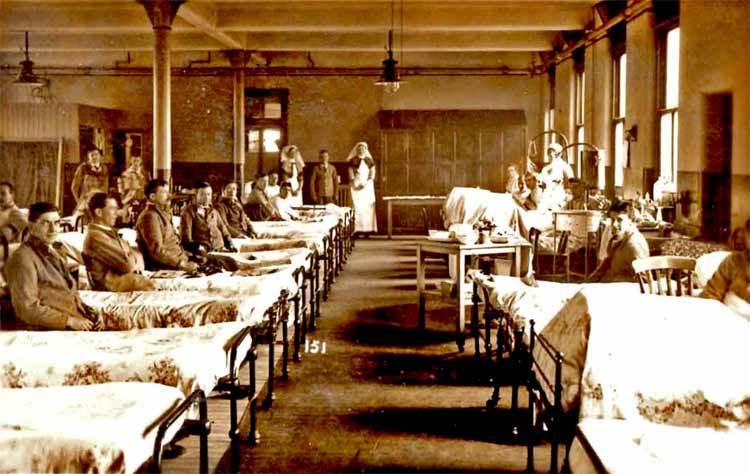

Wounded soldiers were sent to recover either at home, or in hospitals run by the Voluntary Aid Detachment, usually in stately homes – Stokesley’s VAD hospital was in the Manor House.

Harry Carter of West Green was one of those sent home with his injuries. He was with his unit on Monday, May 24, 1915, when the Germans opened up with not only artillery, machine guns and rifles but also with their latest weapon: chlorine gas. Witnesses said the gas formed clouds 40ft high which drifted on the wind across the British line. Harry was sent to recover from the effects in a sanatorium in Aysgarth, where he was diagnosed with tuberculosis, as the effects of gas attacks were unknown to doctors at the time. Pte Carter died at home from his injuries, unable to speak, aged 25. He was given a military funeral Stokesley and the Last Post was sounded over his grave. His body lies in Stokesley cemetery along with four other war graves.

The town’s Book of Remembrance, which is cared for by the Reverend Paul Hutchinson, in St Peter and Paul’s parish church, is a tribute to the 54 Stokesley men and boys who died in the conflict. It is kept in a glass case in the nave of the church, and was assembled by the Stokesley people in 1927. Charles Hall, who had been injured in the war, organised and coordinated a small group of volunteers, several of whom were relatives of fallen soldiers, to compile the book. Some were involved in decorating different pages while others collected information and photos. It is a beautiful book, a true labour of love.

The horrors these young men faced are unimaginable. They were so young, and so full of the best intentions, believing they were doing the right thing for their country and trusting in the generals to lead them to victory.

The loss of sons, husbands and fathers left widows coping with the aftermath of everything from grief to a lack of money. They were given small pensions and often remarried, just to survive.

Many soldiers, of course, did make it back, but they and their families had to cope with the mental and physical effects of combat.

Stokesley honours its fallen in a big way, through the tireless efforts of friends, families and also historians who want to uncover the stories so they can honour the men who gave their lives. This year, because of the centenary, there will be even greater interest in remembering the town’s fallen.

Thanks to Keith and Val Burton whose research into the town and the First World War can be seen at stokesleyheritage.wikiddot.com. Thanks also to Rev Paul Hutchinson for allowing access to the Book of Remembrance.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here