DAVID Beattie’s journey from chemical engineer to coffee trader has been an unusual one.

It began when he took a break from his work as an engineer on Teesside and took a train from Middlesbrough at the start of a journey around the world. He travelled across Europe, Hong Kong, Russia, Mongolia and China. But it was in the Sumatran jungle that he met the group of coffee famers who altered the course of his life.

While travelling around Sumatra on a moped, he made a detour to a place that sold civet coffee, also known as kopi luwak or “cat poo coffee” created from coffee berries which have been first eaten by the civet cat and then... you can guess the rest.

The coffee’s superior taste is supposed to arise from the cats selecting the best beans and then partly digesting them. But David discovered the slightly mythical process had become a sad and inhumane business, finding wild cats caged and force fed.

“In Indonesia they get a good price for kopi luwak but I didn’t realise how cruel it was,” he explained.

“So I drove around on a moped and I ended up spending three weeks at a coffee place somewhere called Lake Toba. I ended up befriending the guys round there and they pointed me in the direction of the coffee farmers.”

He spent the time learning the art of coffee roasting and his respect for the farmers grew, along with his concern at the pittance many were earning for the long, back-breaking work they did. It was barely enough for them to survive.

“I tried to help them by selling their crop – I wanted people to buy their coffee – but the cost and risk was too great,” he said.

That was when he hit upon the idea of creating his own coffee roastery back home in the UK.

With the help of a Harrogate-based speciality coffee importer, he is able to help coffee farmers by paying a sustainable wage for good quality coffee from the North Yorkshire village of East Rounton.

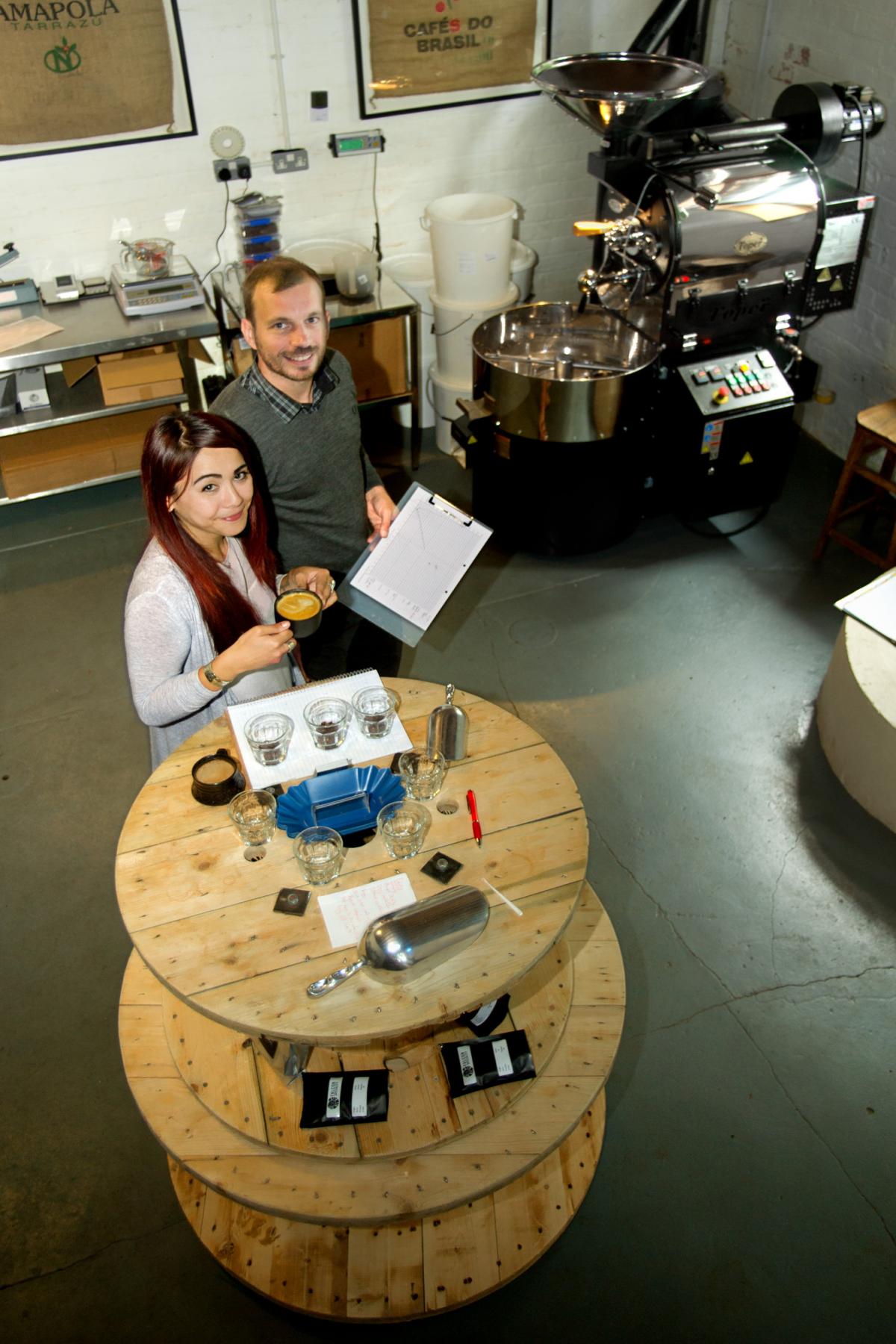

He and partner Tracy Lee began work on their business in September last year. About six months ago they began working full time with the business. They were recently named specialist retailer of the year in the Flavours of Herriot Country Awards for 2014.

The coffee is bought at 140 per cent of the commercial market price – to ensure a sustainable price from the farmers. The coffee can be traced right back virtually to the plant the beans were picked from, as they work directly with farmers’ co-operatives in Ethiopia, Columbia, Sumatra and Kenya.

They started off producing speciality coffee in small batches, roasted on demand for retailers, restaurants and other suppliers and also sold at farmers’ markets.

Curious customers are often invited to visit the coffee roastery to taste the different coffees and watch it being roasted.

It’s in an old, brick granary, once used to store grain. The building’s grain mill still stands in the building, among cafetieres, old leather sofas and coffee bean sacks which hang as curtains from the low windows.

At the heart of the operation is an elegant, Victorian-looking coffee roaster, full of polished funnels, dials and gleaming back metal.

David says being a coffee roasting has many parallels with his background in chemical engineering, when he worked as operations manager at industrial gas suppliers BOC.

“I was a chemical engineer in Teesside and the whole production of process of roasting coffee and the different methods relate to engineering. A lot of coffee roasters are ex-engineers in some capacity.

“When you go to the processing plant in Teesside it’s got exactly the same components, just on a smaller scale. You have a part that does heat transfer cooling... all of it is a chemical process. All we’re doing in monitoring and managing.”

But there is still no replacement for human judgement.

Once the beans are dried and roasted, the final stage is the development phase, when the flavour begins and it becomes drinkable. It requires some hovering over the coffee roaster to make sure this is done just right – whether it’s strong, dark Sumatran beans, which need to be roasted for longer, or lighter African coffee.

Despite the distance this tea-drinking nation has come in embracing coffee, David says we still have relatively conservative tastes when it comes to coffee.

“There are some really wacky coffees out there, really fruity coffees. Whilst we love them, it’s still a bit of a battle introducing them to the wider public.

“For instance, there’s an Ethiopian coffee which smells like Skittles sweets and when you concentrate that in coffee it tastes really fruity. But people have an expectation of how a coffee will taste and they often think something is wrong if it tastes different from that.”

Despite every high street having at least one well-known coffee shop brand, the UK coffee market still has some catching up to do with Australia and New Zealand.

“Personally, I still think we have a lot of learn about coffee. There’s a lot of speciality coffee shops opening up. Costa and Starbucks have not been bad for coffee. They’ve introduced barista-prepared coffee to an instant coffee drinking nation and they spend all the money on marketing coffee.

“But in places like New Zealand and Australia the quality control is a lot higher. In New Zealand to serve coffee you can’t just be let loose on a machine, there’s much more training. They treat coffee differently.

“It takes around 2,000 man hours to produce coffee but it can be ruined in a second by a bad barista.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here