ON A surprisingly warm and sunny late autumn day, I took time off to join my wife, one of my daughters, two of her sons and two visiting dogs on a walk through one of our local forests.

Comprising chiefly conifers with a large number of colourful larches about to lose their needles along with some deciduous trees in full colour, the hillside forest offers wonderful walks with streams and a lake plus an interesting variety of wild life. As this is partially a deciduous forest, it produces a wealth of wild plants along the lanes and open areas.

Horse riders and other dog walkers were evident, but the dogs and horses seemed happy to accommodate one another in peace and there was no sign of dog fights or nervous horses. One of “our” dogs was a tiny black pup with a lot of poodle in her genes, and from the moment we left the car, it was evident she was in her seventh heaven. She was only four months old and usually lived in the city; never before, I suspect, had she experienced such a huge open world of freedom, excitement, fascinating smells and new discoveries.

One problem she did encounter was that if she galloped through the undergrowth on her exploratory missions, some problems awaited.

These came in the form of the seeds of both the goosegrass and the burdock. Both these plants produce seeds which are covered with hooked bracts; these attach themselves to the coats of animals which brush past and in this way, manage to distribute themselves once the animals have found the means to remove them.

Our little companion soon realised how troublesome were those seeds; she could find them and with her teeth remove the larger burdock burrs, but the smaller goosegrass seeds were not so easy to dispose of. She spent a lot of time removing those burrs from her front legs and chest and we helped her to get ride of many, but the moment she was free of them, she galloped back into the undergrowth in sheer exuberance and immediately collected more seeds. Oddly enough, the larger, older and wiser dog kept away from such dangers and managed to avoid the burrs.

Curiously both these plants once had uses both as medicines and as salads. The seeds of goosegrass were collected and used as a type of coffee while the young shoots, if harvested in the spring, could be cooked as vegetables. Once known as cleaves, juices of the plant were also used as a slimming aid.

The young stalks of burdock were formerly used as vegetables or added to meat broth when peeled and chopped, and were also efficient in easing sores, ulcers and even sciatica.

One bird we spotted in full song was a robin, one of the few species to sing during the autumn. They are known to sing throughout the year and sometimes even at night in the light of a street lamp. The song can sometimes be sad and wistful but nonetheless, it was a welcome addition to our autumn walk in that colourful woodland.

Another bird that can sometimes be heard and occasionally seen in coniferous forests, woodlands and even in churchyards among yew trees, is the tiny goldcrest. This is Britain’s smallest bird, tinier even than the wren, and although there is a native population in our islands, we do receive migrants from northern Scandinavia around this time of year.

The probability is that goldcrests are often heard before they are seen, and in fact that happened during our woodland visit. While walking through a patch of larch trees, now shedding their foliage of needles, we heard the distinctive calls of a goldcrest.

They consist of high-pitched notes that sound like "tsee, tsee" but the birds are so tiny and well camouflaged that it is difficult to spot them among the trees. Small flocks can appear during the winter months and sometimes these will join other species such as blue tits and great tits.

Smaller than a bluetit, the goldcrest’s main colouring is a rather dull green on the upper parts and paler below, but its main method of identification is a highly visible crest of yellow with black edges.

This is slightly duller on the female but if the bird is alarmed, it may raise the crest in an aggressive display.

Its near relation is the firecrest, of similar appearance, size and habitat, except that its crest comprises a bright orange stripe bordered by black edges with white stripes over the eyes. I have to admit I can’t recall ever seeing a firecrest.

It all means that a woodland walk at any time of year with or without dogs will be full of interest.

Saxon relics

A recent visit to Masham with lunch at the renowned Black Sheep Brewery, reminded me of several curious facts within this lovely old market town.

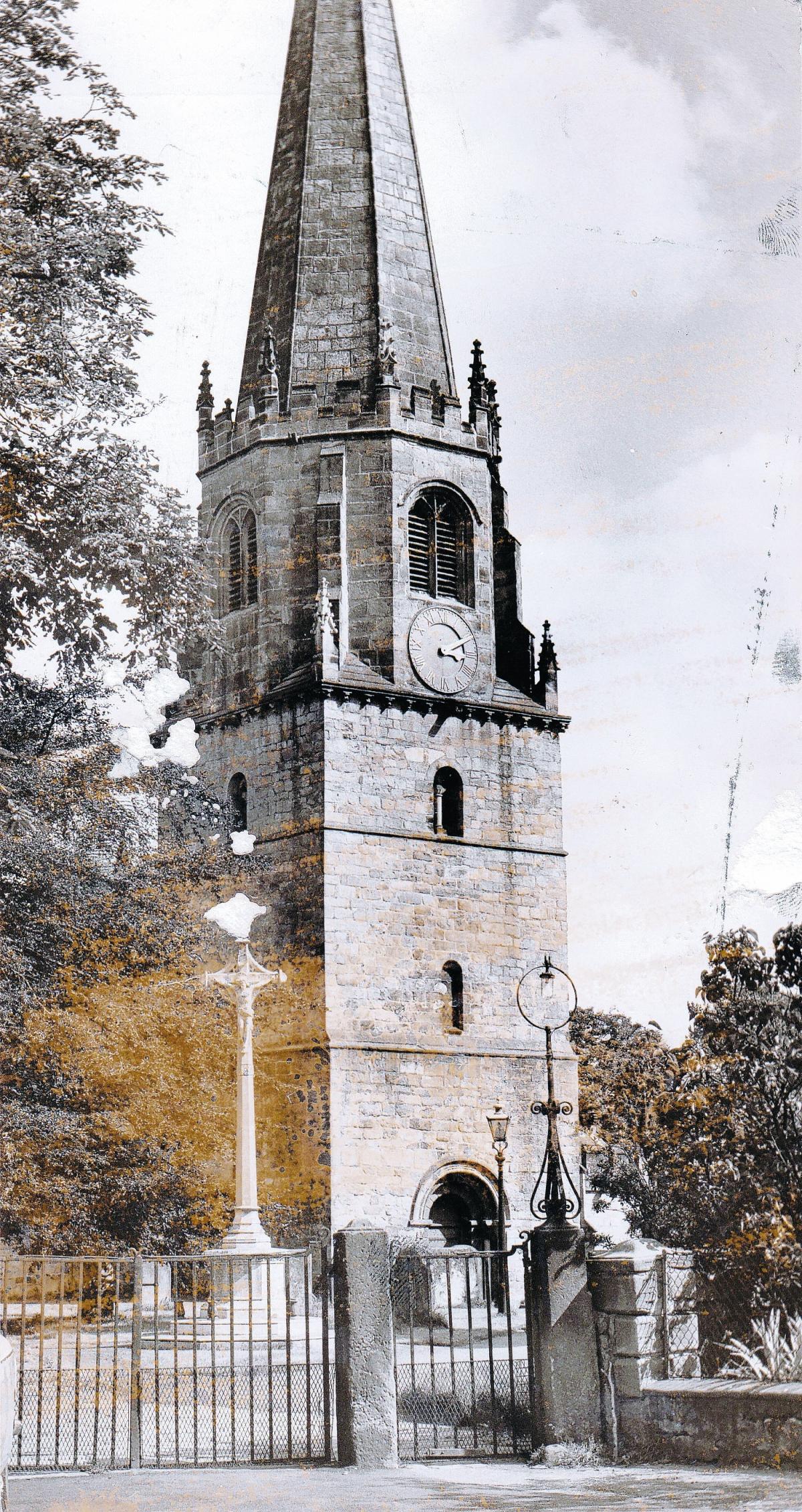

One involves the mysterious and very tall but very old pillar in the churchyard. It is thought to be more than 1,000 years old and bears some old and extremely worn figures. It is thought they might represent Christ and his 12 Apostles because the church is believed to date from Saxon times. It is thought that some Saxon stonework survives in the west wall while ancient stone parts may be former Saxon crosses.

Dedicated to St Mary the Virgin, this former Roman Catholic church has, throughout its life, undergone many alterations and improvements. In the 15th century, the Norman tower was improved by the addition an octagonal lantern and the clerestory added to the nave.

The ancient Roman Catholic family of the Scropes has long and historic links with this lovely old church and constantly improved and repaired it before the Reformation. Like so many other parish churches, it suffered at the hands of the reformers, one outcome probably being the removal of the Norman font. Now in the tower, such removal was a feature of many Edwardine Visitations.

Edward VI (1537-1553), the son of Henry VIII, ascended to the throne in 1547 aged nine. Urged by his Protectors, the Duke of Somerset and the Duke of Northumberland, he set about a nationwide plan to erase Catholicism and began by making the Catholic mass illegal with the Act of Uniformity in 1549.

His next task, again on the advice of his Protectors, was to announce he was to make a Visitation to all churches to ensure they had removed evidence of their former faith. It involved the disposal of Catholic icons and statues of saints, and included the whitewashing of church walls to conceal religious artworks. Many churches in this region suffered. Another of his actions was to remove fonts. This may explain why Masham’s old Norman font was removed; its replacement is a copy.

One interesting occupant of the churchyard is a man called Julius Caesar, but he is not the ancient Roman; this is Julius Caesar Ibbetson, who was an outstanding artist of rural scenes, especially those of the Lake District.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here