Chris Lloyd looks back on how the Dales were drenched in disappointment 90 years ago this week

'LIKE a swift sweeping black plague, the darkness became intensified and Penhill disappeared,” wrote the D&S Times’ Wensleydale correspondent atop Zebra Hill, near Bellerby, 90 years ago. “Deeper and deeper yet the darkness grew, and a moment later it was completely dark. It became very cold. The transition had taken 20 or so seconds.”

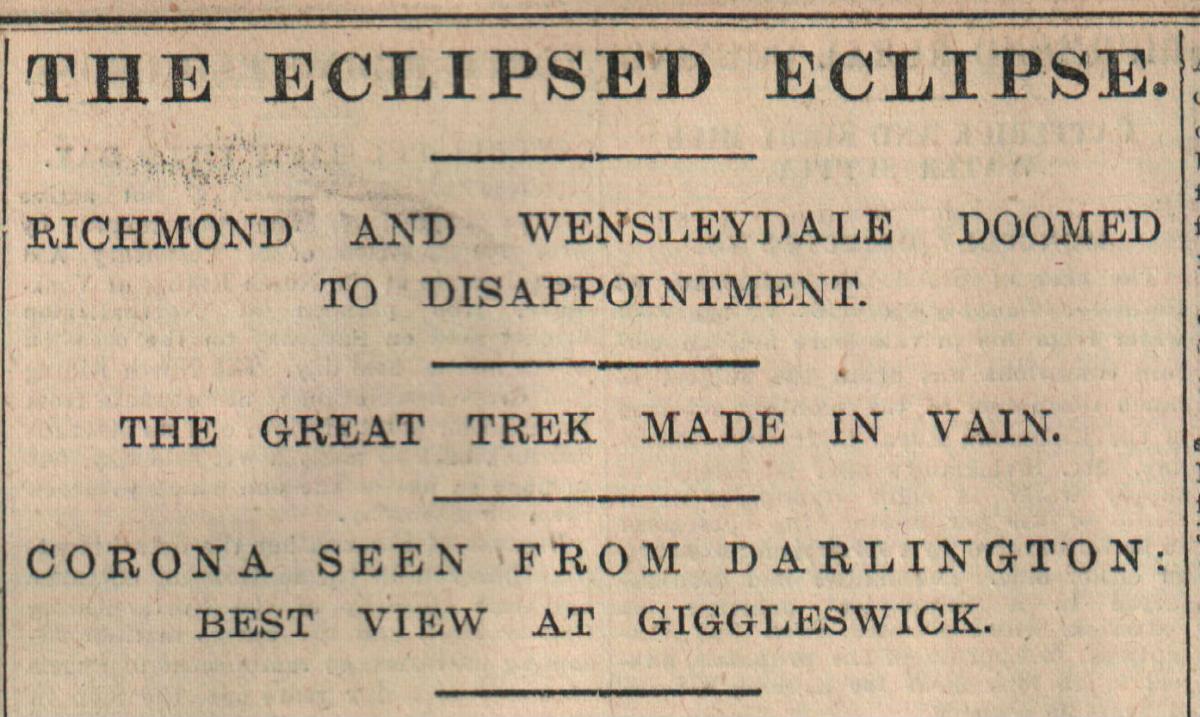

Despite the unnamed correspondent’s enthusiasm, the Dales were really drenched in disappointment. As the headline in the D&S of the first week of July 1927 said: “Eclipse eclipsed.”

“A caprice of clouds” had covered the sun at the moment of total eclipse, obscuring the view of millions of people down below.

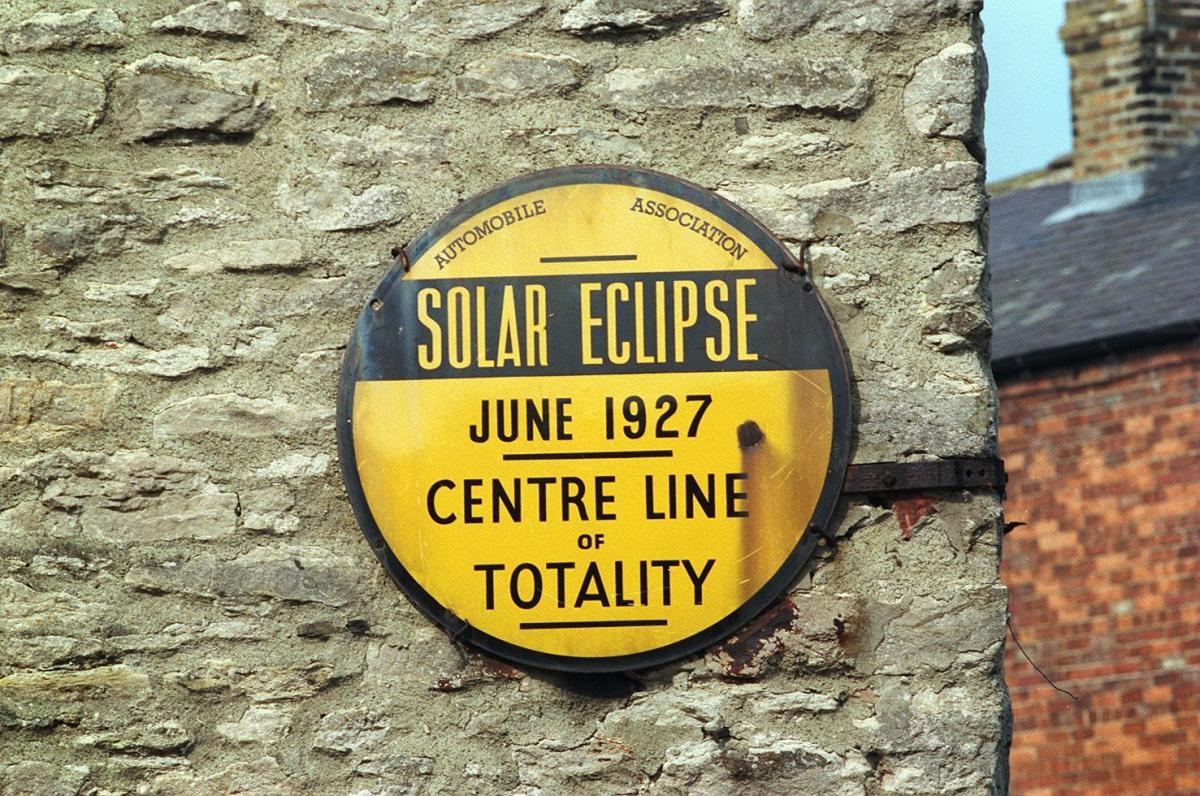

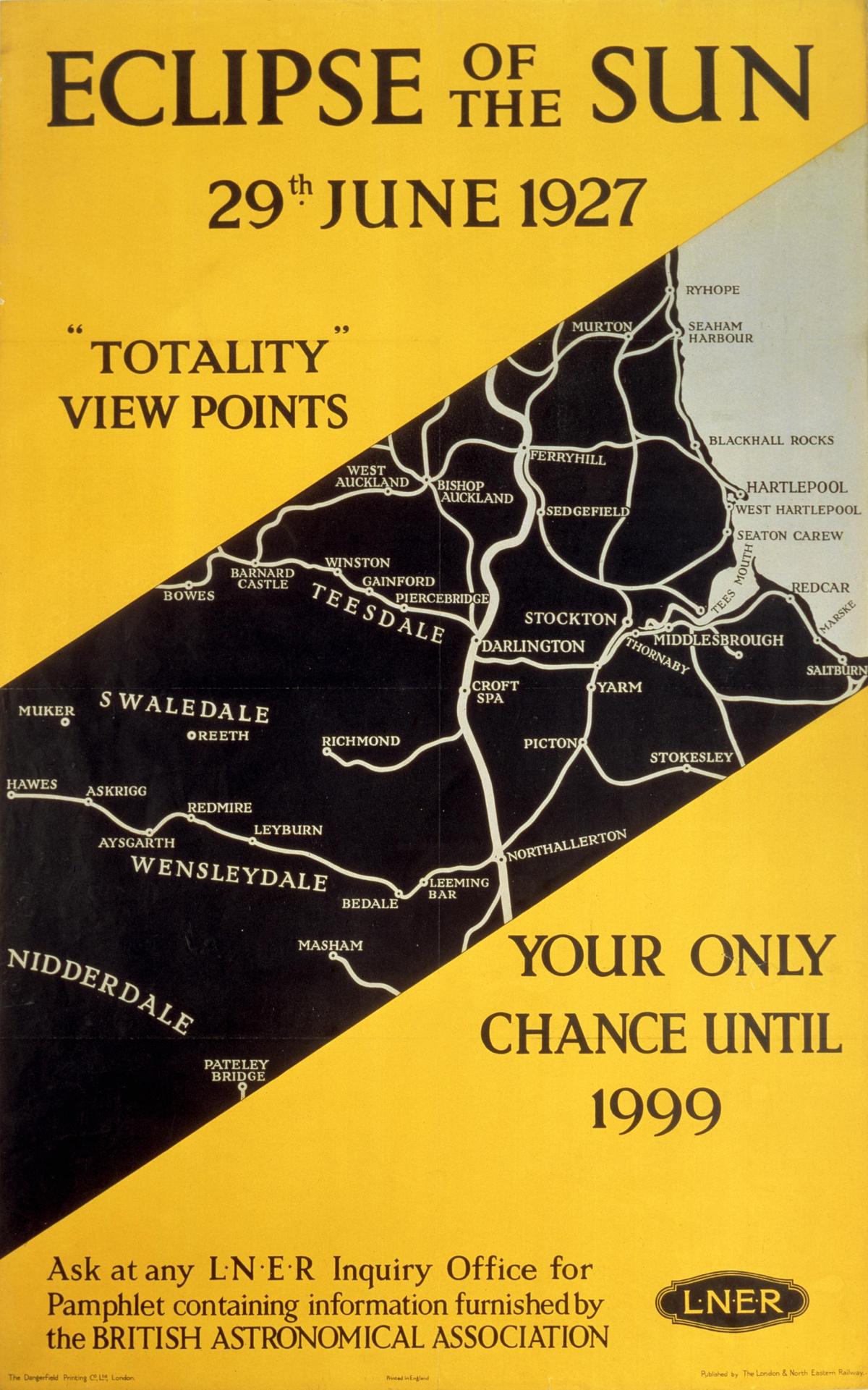

And there were millions. The "band of totality" stretched from Llandudno on the Welsh coast, through Blackpool and Lancaster before crossing the Pennines. In the North-East, Muker, Bowes, Barnard Castle, West Auckland, Murton and Ryhope were on its northern edges, and Pateley Bridge, Northallerton, Stokesley and Saltburn on its southern fringes. Leyburn and Darlington were pretty central; Richmond was smack bang in the middle – and to this day, a large yellow AA sign marks its centrality.

The eclipse began at 5.26am on the Wednesday morning and was all over by 7.17am. "Totality", when the moon completely obscured the sun, lasted for 23 seconds at 6.20am.

The last total eclipse visible in England had been in 1724; this was, according to the LNER railway company, "your only chance until 1999".

It organised what is still the largest-ever movement of people by rail, bringing about three million into the North-East and North-West. Special excursions ran from all over the country and any spare buffet cars were shunted into convenient sidings to act as burger-bars for the milling throng (these were the days when places like Hawes, Leyburn, Bowes, and Gainford all had stations and sidings).

Trains ran all night into mainline Darlington, Northallerton and Croft Spa, where passengers were either transferred to other trains or took buses into the Dales. For example, at 3.55am a special train arrived at Croft Spa bearing 600 public school boys from Oundle who then took a motor bus to Richmond.

Eight special “eclipse excursions” pulled into Richmond station in the early hours. They disgorged 2,200 people from King’s Cross, Edinburgh and East Anglia, and parked up in sidings between Easby Abbey and Broken Brea, ready to pull back into the station when the excitement was over.

Other companies also benefited from the eclipse excursionists. Cinemas and theatres stayed open all night, as did many shops - nearly all of them promising that their prices "could not be eclipsed" by their rivals.

In Wensleydale, every tourist bed had been booked since February, and so thousands of people were under canvas. "The slopes on each side of the valley are reminiscent of military bivouacing for the night,” said The Northern Echo. “Fires glow and lights twinkle from the bell tents by the score erected by visitors who are camping out."

"From the way in which the different amusements of the town were patronised, it was obvious that a fair proportion of the populace did not go to bed at all," reported the Echo.

In Leyburn, Middleham and Richmond castle there were eclipse balls, with people dancing through the night until the sun came up, when the dancers all headed for the best, highest vantage point, all armed with their eclipse-viewers (smoked pieces of glass).

There were 200,000 watchers in Hartlepool, including 100,000 packed onto the beach at Seaton Carew. There were 10,000 gathered on the bank above Stapleton, near Darlington, and another 10,000 from Bishop Auckland collected around Leg's Cross. Richmond had 35,000 visitors on its racecourse alone; Leyburn and Bedale 20,000 each.

But when dawn broke, there was nothing but disappointment. "The sun appeared to have had a bad attack of stage fright at the last moment," said the Echo. "It is reported from many areas that he hid himself in a bank of clouds at the point that totality was reached."

Richmond seems to have taken the disappointment worst of all. As the moment of totality approached, the crowds fell into a deep silence, preparing themselves for "the most solemn, awe-inspiring sight that ever appears in the heavens". But as clouds rolled across the sky, eclipsing the eclipse, "a faint gasp of chagrin broke the spell. Disappointed people flocked to the racecourse exits for the most part in tense silence, eager to get away".

Yet there were some bright spots. "Northallerton and Darlington were spots in the eastern area of the shadow band in which some spectators saw the corona. They were, however, a handful of fortunates amongst very many thousands of disappointed."

Even in cloudy areas, though, a darkness fell as deep as night. The temperature dropped a couple of degrees, a dew fell in Richmond. A cow being milked in Nunthorpe went inexplicably dry for the 23 seconds of totality; in Stapleton hens rushed to roost in their house, only to pop out again looking confused when the sun re-emerged.

And in Hartlepool "a man was so affected by the eerie darkness that he broke down and burst into tears".

The eminent astronomer Dr WJS Lockyer had been camped on the top of Olliver Docket Mount, near Gilling West for a couple of weeks with two companions and a dog called Hickboo, preparing a 45ft camera for its 23 seconds of exposure.

“It was a beautiful fiasco,” he told the D&S.

In fact the only person who got a good view was ES Nash, an Echo reporter in a plane above the Dales and the clouds. "I saw the corona blazing like some strange and wonderful lamp in the heavens," he wrote. "Ultimate triumph and joy and a deep feeling of awe were my outstanding emotions yesterday whilst the greatest spectacle of Nature was being enacted in the skies."

It must have been doubly irritating for the thousands below him – not only could they see nothing, but all they could hear was the drone of his plane overhead.

The D&S’ man on Zebra Hill was making the best of it. After the darkness had fallen like a black plague, he said “more wonderful transformation was still to come”.

He concluded: “Like a swift drawing of an immense curtain by a magic hand, the blackness was swept away to the south and in a few seconds all was restored to light, the cold decreased and the crowd breathed a huge sigh of wonderment.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here