MUCH has been written about the mines in Swaledale and Wharfedale but mining in Wensleydale has had little press by comparison.

Starting in 1971 and spending the last nine years working on the project full time, I have tried to address this imbalance. I hope that what has emerged is not only a history of the extractive industries but also a history of Wensleydale.

Wensleydale mines produced a number of minerals — lead, zinc and coal are the obvious ones, but also barium minerals and fluorspar. Wensleydale is well known for its limestone quarries, but the quarrying and mining of sandstone flags and slate was a major industry from the 15th century. While the Dales were created during the Ice Age, man’s management of the land has created their distinctive appearance. Most of the escarpments were in the first place quarries for sandstone quern stones to grind grain or limestone for building field walls, roofing and homes, as well as liming the land.

The dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century brought about great change and provided a major impetus to agriculture and the extractive industries. As farming incomes rose, farmers could make greater use of lime and so Preston Moor Colliery became a major producer, commanding an annual rent of £400 in the 1620s. Greed and jealousy led to many disputes.

One dispute was over the supposed non-payment of rent to Lord Emanuel Scrope of Bolton Castle for Preston Moor Colliery. At one point Thomas Rudd, the tenant of the colliery, was put in York Jail.

The search for lead resulted in some spectacular discoveries, particularly at Cobscar, near Redmire, in 1650 and much later at Keld Heads Mine near Wensley station in the 1840s.

Each new discovery elicited a fresh frantic search in adjacent areas, sometimes successful but more often disappointing.

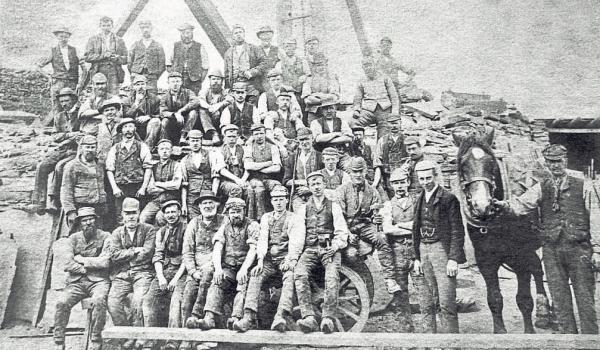

Each boom brought in fresh people from near and far, men from Wales came in the 1760s when an industrialist from the country leased the Apedale Mines. Many of the smaller mines were worked by groups of miners who often struggled to find enough ore to make a wage to live on. Sometimes these miners discovered a large body of ore which then induced the mineral owner or previous lessees to make claim to the rights to work the mine, robbing them of their good fortune. One such event in 1369, at the head of Bishopdale, brought miners in conflict with Henry Percy, the 1st Duke of Northumberland, who had them imprisoned in the Fleet in London.

The boom and bust of mining led to periods of great hardship, high provision prices effected all in the Dales and there were at least two so-called “bread riots”. One in 1757 ended with the hanging of two men at Tyburn. A second in 1796 ended less dramatically but there was little or no relief from poverty well into the 19th century. The Dales population was surprisingly mobile, often making a shift to the industrial towns of Lancashire and West Yorkshire or the coalfields of County Durham, but then returning as the situation changed. There was no guarantee of full employment in the mills or mines of Lancashire and Durham. In the 1830s and 1840s, many went to America and in later years to other New World countries.

Stories of harsh working conditions come to light at Preston Moor or the avarice of William Waller at Cotterdale Colliery, who systematically ruined his manager Ewan Waller in the 1690s. Even in 1826-27 a lively dispute over the right to work Storth Colliery near Gayle saw John Tatham beaten so severely as to endanger his life. Imported coal by the railways ultimately out-competed the Dales collieries but at first the railway owners, who were also directors and owners of major collieries, set out to rig the price of coal and the Dales collieries were able to struggle on for a while at least. One coal merchant, William Oxlade, tried to beat the railways and bring in cheaper coal, but was utterly thwarted.

In the last half of the 19th century, the outlook for the Dales mines begin to decline.

Preston Moor Colliery, supplying coal for lime burning at Harmby Quarry, gradually lost its orders to the railway. West Scrafton and Fleensop in Coverdale did much better, being further from the railhead. Lead mining effectively came to end when Keld Heads Mine closed in about 1889. Dales’ mines could no longer compete with the large virgin deposits of lead ore in Spain and America. The only English mines which could compete were those with much higher silver contents in the lead than the Yorkshire mines had.

The Wensleydale Railway continued to take flags from Burtersett, Gayle and Staggs Fell quarries but here, too, competition from larger quarries close to the major markets of West Yorkshire and Lancashire gradually brought their closure. Limestone quarrying did eventually become a major industry but strikes at the blast furnaces and coal mines often brought the quarries to a standstill.

The Second World War and road building was the main reason why a sustainable industry was formed, which can still be seen today at Wensley and Leyburn quarries.

l Mines and Miners of Wensleydale by Ian Spensley will be launched at the Dales Countryside Museum, Hawes from 11am to 4pm on September 20. All welcome.

Copies of the book are also available from Ian Spensley, Aumonds Lear, Redmire, Leyburn, North Yorkshire, DL8 4EQ. Price £15 plus £4 postage and packing.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here