The billeting officers

WITHIN the reception areas, billeting officers were appointed. In the Northallerton area, initially, billeting officers were volunteers and most were local councillors. Their role was stressful one – the clerk to Stokesley RDC “had broken down under the strain”. The volunteer billeting officer for Romanby, a Northallerton RDC councillor, resigned in October 1939 because, as he later stated, he “became an enemy to all in the parish ... People stood on [his] doorstep day after day asking for relief from billeting.”

The main job of these officers was to provide a billet for each evacuee, but they also had to make regular visits to check on the welfare of evacuees and to ensure that the householder did not make fraudulent claims for those who returned home.

By the end of 1939, increasing opposition was emerging, and Councillor Norris, billeting officer for Northallerton UDC, raised objections to children being prevented from going home at weekends, saying that householders were being deprived of a “weekend of privacy”.

In January 1940 he referred to vandalism caused by the evacuees in Northallerton.

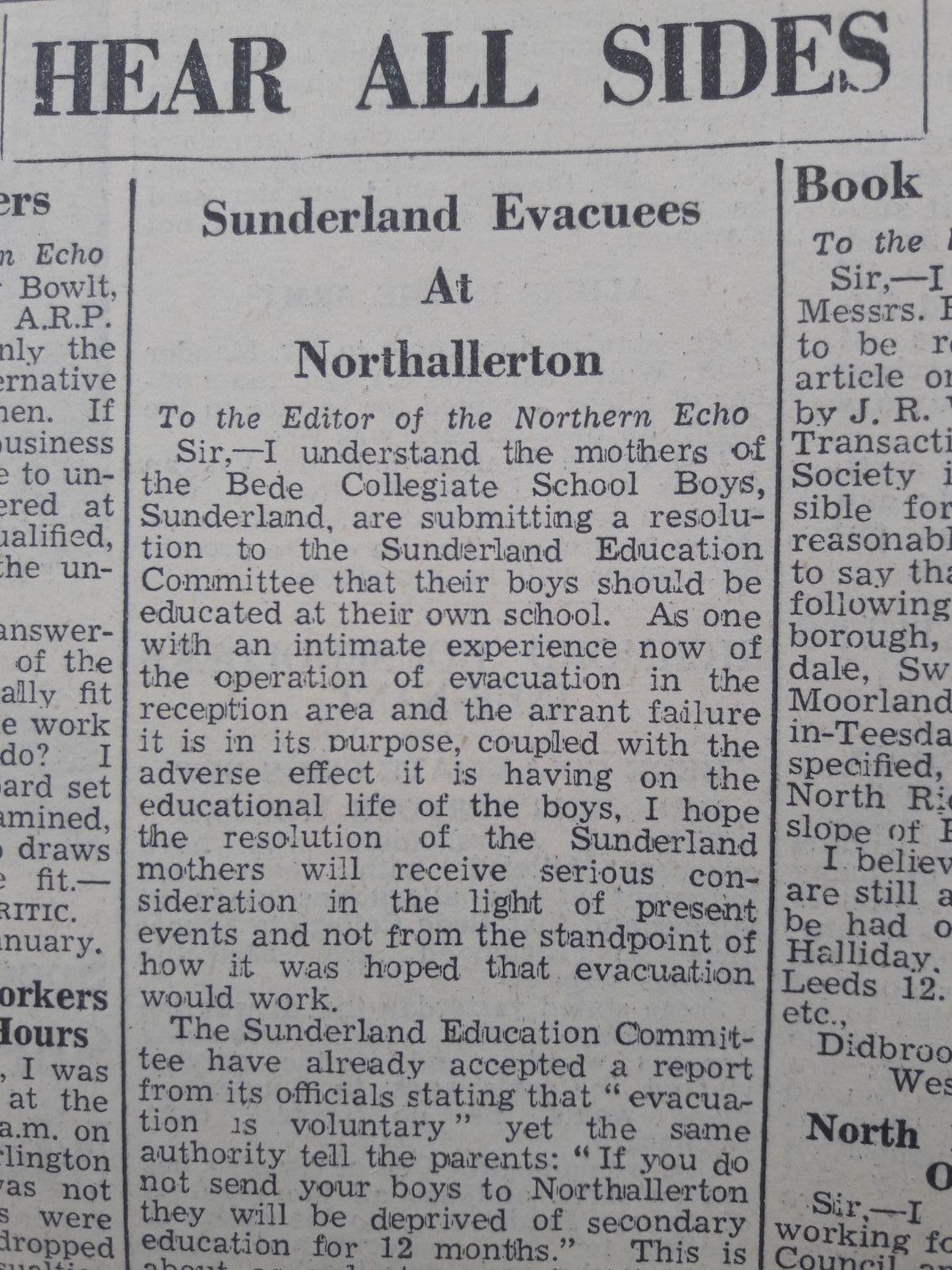

Councillor Norris wrote to The Northern Echo on January 17, 1940 to express his concerns. Was Norris aware that this letter would have been read by many Sunderland parents, since The Northern Echo was their principal local daily newspaper?

His letter claimed evacuation had failed, leaving parents of evacuees distressed and the home life of the billets “completely desecrated”.

He resigned as billeting officer for Northallerton on March 7, 1940.

In the wider community Councillor Norris probably had greater support among those disenchanted with the evacuation process, perhaps because fewer than the expected numbers of evacuees remained in the town.

The evacuees

AT the point of departure, a number of children were so badly shod that they were given extra sandshoes by the authorities, reflecting the extreme poverty of many evacuees, particularly from Gateshead. In certain parts of the town, many children went about in bare feet.

Evacuation potentially brought poverty home to their families. One social worker wrote: “I have seen an unemployed father in tears because of a son’s letter saying that, while he knew his father could not send the ten shillings demanded by the hostess for clothing, he would rather come home than endure the situation any longer.”

Concerns about health and the poor condition of evacuees were heightened by the increased incidence of infectious diseases. The Darlington and Stockton Times reported that two evacuees in Bedale had contracted diphtheria. Many children were described as being “verminous” and in Northallerton small-tooth combs were unobtainable due to demand. Cases of impetigo were common.

Not all evacuees had unhappy stories about their stay in Northallerton – some had relatively uneventful experiences, others had a rewarding time, and some did not want to return home. Each evacuee had a unique experience, and none was “typical”. Many were homesick, some bullied by local children, and they had frequent changes in billets. Two unhappy evacuees planned to escape from Northallerton by boarding a railway wagon at night.

Children were made aware of the dissatisfaction felt by the hosts about the allowances received. In at least one instance boys had to cycle from Sunderland to Northallerton and back in one day to retrieve their belongings, after being told they would not be accepted on return from the Easter holidays of 1940.

In Northallerton, as throughout the country, many evacuees returned home by the end of 1939 or early in 1940, during the period of the phony war.

1940

DURING the early part of 1940 the need for a second wave of evacuation was created with the German invasion of the Low Countries and France. There was opposition to further evacuees in Northallerton and the arguments put forward were that there was a lack of facilities for full-time education; a shortage of billets for nurses attached to the local hospital; and a reduction in available accommodation since the original survey was made. A number of 400 evacuees was finally agreed.

However the final stage of the first wave of evacuation, which began in September 1939, was the decision to recall the headmaster and staff of the Bede Collegiate School in September 1940.

*Harry Fairburn is a retired bank manager with a MA (Local History) from York University. He is a prize essayist for the Yorkshire Society. Recent work undertaken has been on women’s suffrage. He is a volunteer with the Ripon Museums.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here