In September 1939, thousands of inner-city children were evacuated to the safety of the countryside as fears of mass-bombing grew during the early days of the Second World War. Historian Harry Fairburn – himself an evacuee – has researched the impact of the evacuation on Northallerton. His work reveals how the town and its people coped – and what the youngsters made of rural life. In the first of two features, we publish extracts from his research

THE evacuation of schoolchildren to Northallerton from 1939 to 1940 was one of the most significant events to take place in the town during the Second World War, but there has been little research on the topic.

A former evacuee myself, in 1939 aged six I went from Gateshead to the village of Nunthorpe in the North Riding. I stood at Gateshead railway station in 1939 failing to appreciate why it was necessary to leave home or knowing where I was going.

I lived in the Nunthorpe billet for only a few months before returning home in January 1940, like so many other evacuees at the end of the so called “phony war”.

At home, our air-raid shelter had restricted access which made it difficult for my parents to enter – my mother had to wear protective headwear to safeguard herself from head injury. And on the nights when bombing took place on Tyneside it was either too cold or the shelter was too full of water draining from the surrounding earthworks, so a bed was made up below the dining room table. With so many disturbed nights and the absence of schooling I was evacuated a second time and secured a billet in Cumberland.

Northallerton

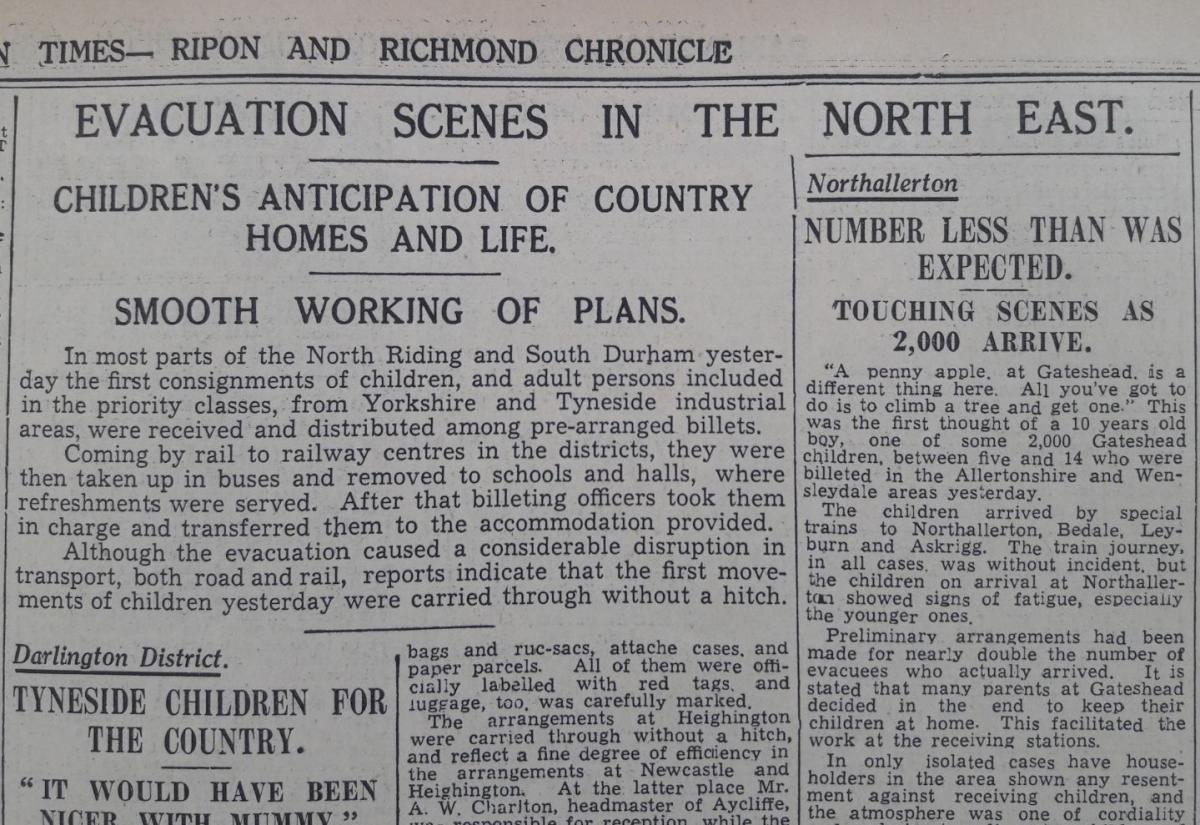

IN early September 1939, hundreds of children together with their teachers, helpers, and some parents, arrived in the town as part of the government’s evacuation scheme. Northallerton and its surrounds had been designated as reception areas by the Anderson Committee, set up in 1938 in response to anxieties about enemy bombing.

Northallerton Urban District Council believed that there was a prospect of the town’s population being increased by 20 per cent at a stroke – the arrival of such numbers was likely to put stress on the social fabric of the town.

The evacuation

THE evacuation of children from Gateshead took place on September 1 and 2, 1939, each child carrying spare clothing and gas masks. North Riding County Council reported that 12,000 evacuees were expected from Gateshead but only 7,500 were actually received. It was planned that 30 trains would be laid on to transport all Gateshead evacuees to the North Riding and South West Durham. At a meeting of the Northallerton UDC on September 7, Councillor A.E. Skelton reported that the town had received 639 evacuees from Gateshead on the previous Friday and Saturday, and would receive a further 364 evacuees on September 10 and 11.

These evacuees mainly came from the Bede Collegiate Boys School in Sunderland, where some forward planning had taken place, with pupils and prospective hosts being linked in advance. In the case of pupils from Gateshead, however, the arbitrary selection of children by hosts often threatened to separate siblings. One evacuee perceived that “the best dressed children were chosen first” with others left to the end of the selection process.

On arrival, the children were given a meal before going by bus to the new homes.

The reception and the billets

MANY had a warm welcome to Northallerton. One urban district councillor providing billets for Gateshead children said that: “I am trying to learn a new dialect under the tutelage of the two young men from Gateshead billeted upon me. I shall be able to speak Tyneside.”

However, some weeks later there was public criticism of evacuees by the chairman of Northallerton Rural District Council, relating to the frequent changing of billets. He said that: “The persons billeted are unreasonable and unthankful. We have done our best and we have found them really good homes and still they are not thankful. We have had enough of it.”

Some evacuees experienced unusual situations. One, from a leafy suburb of Gateshead wrote of “outside dry closet, twin ones, and the tin bath in front of the kitchen fire”. Another, in a billet in Market Row, Northallerton, wrote of “a tap on the wall opposite the front door for fresh water and the toilet at the bottom of the lane. As I remember it was a large old-fashioned wash house – bit frightening.”

A common complaint by the hosts was the perceived inadequacy of the allowances paid to them – in at least one instance, the host wrote to the parents of the evacuee asking for increased financial support. Hosts were paid 10s 6d a week for a single evacuee but where there was more than one the rate was 8s 6d. Dissatisfaction with the allowance resulted in one host in Northallerton denying electric light to a pupil revising for his school certificate. The young man concerned had to resort to torchlight under his bed clothes.

- Harry Fairburn is a retired bank manager with a MA (Local History) from York University. He is a prize essayist for the Yorkshire Society. Recent work undertaken has been on women’s suffrage. He is a volunteer with the Ripon Museums.

- Next week: The billeting officers, the evacuees, and what happened in 1940

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here