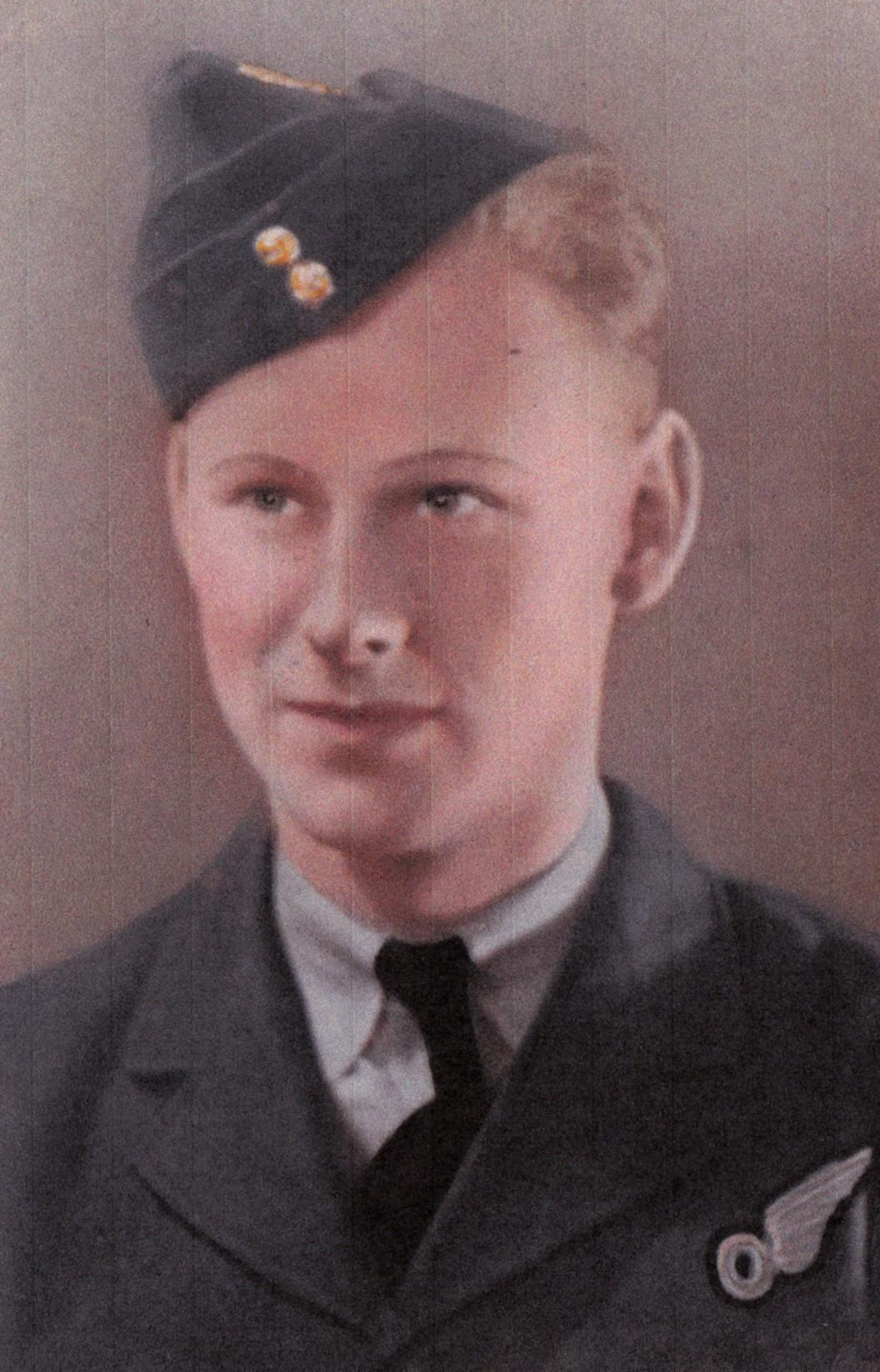

THE TRAGEDY of a daughter not knowing how her father died in the Second World War was finally laid to rest yesterday, when a German researcher arrived in village in North Yorkshire.

Reginald Renton died when the Stirling bomber he had flown in was shot down whilst on a mission to Germany in September 1943. How and where he had died remained unanswered questions for his family in Bishop Monkton, near Ripon, until Erik Wieman got in touch.

Erik is a former Dutch paratrooper who now lives in Germany. He operates a German search team with friend Peter Berker, who finds sites where English and Allied personnel died in Germany and investigate them. They then share their research with any living relatives and pass on any personal belongings or other items to them.

Erik had answered an appeal on the internet from Richard Fieldhouse, the editor of community news site for the village who wanted to know if anyone knew the identity of “R.Renton” named on the village war memorial.

He was able to tell them that Sgt Renton had died in an Allied bombing raid in September 1943 in Ludwigshafen and that he had found the crash site.

Erik gathered together some pieces of the wreckage – including the bomb release trigger from the aircraft which was the last item Sgt Renton had touched – and arrived in the UK on Saturday evening to present the items to his family.

He stayed long enough to attend the village Remembrance Service before flying back to Germany on Sunday afternoon.

Sgt Renton’s granddaughter, Sally Anne Lightfoot, said it had been particularly emotional for her mother, Valerie Renton, to see the plaque, while great grandson Will said the information had allowed him to flesh out a character he had never known in his family.

A representative of the family of the craft’s radio operator, Sgt Leo Harris, was also presented with a plaque. Sgt Harris had bailed out of the plane, but it was flying too low to enable him to open his parachute. It was given to John Wheatley who will fly out to New Zealand next year to present it to Sgt Harris’ family.

Erik said he didn’t even have to scour local fields looking for the wreckage. A man in his nineties pointed to the exact part of the field where the plane had come down on his father’s farmland, while another local resident pointed out where the plan’s wing had come down, allowing him to put together what had happened to the Stirling bomber in its last moments.

The memory of the crash was still very clear in some local residents’ memories and one person who as a boy had discovered the parachutist’s body broke down in tears as he recounted it.

Erik says he feels there is an urgency to his work as many of the clues to the sites still lie in people’s living memory.

“Time witnesses are the golden link,” he said.

“Because when they die a lot of the stories disappear. That’s why I switched from excavating Roman sites – they’ve been in the ground for 2,000 years and can wait some years more. But I don’t have much time for this.”

Erik says his next goal is to get a memorial stone put in place at the site of the crash, and possibly a geocache at the site and others like it

“When I was searching the site, walkers and joggers were passing the site, asking if I was looking for gold or something. I told them what I was looking for and many of them said they had walked past for years and never known about the crash. If there’s a stone placed there, then people can at least stop and have a read and a think and then these people will never be forgotten.

“It’s very important that their names are known.

"Someone once said, “People are only dead when they are forgotten.” Who wants to be forgotten? Sgt Renton is remembered here, but not in Germany, but with things like memorial stones people’s stories never disappear.”

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here