Darlington Choral Society is at the centre of a mystery more than 150 year after its sensational first concert. Chris Lloyd tells the remarkable story

TOMORROW night, Darlington Choral Society is to be reunited with a silver-tipped baton that was presented to its first conductor more than 150 years ago.

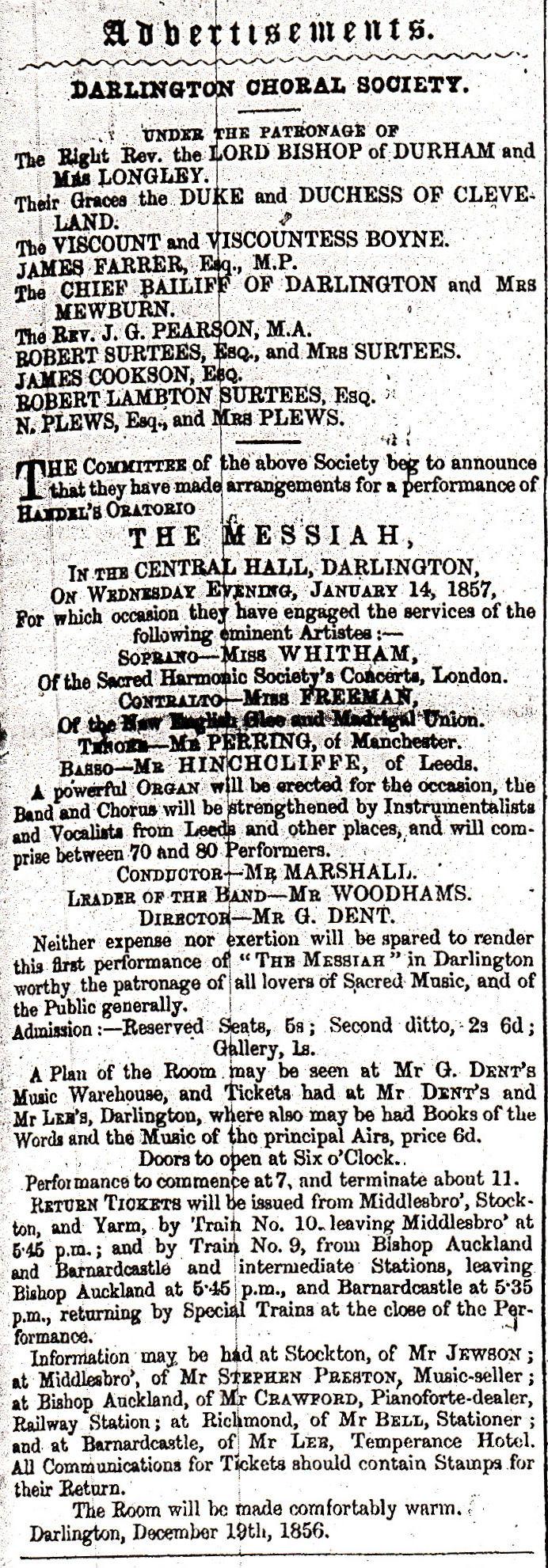

Appropriately, the baton will be wielded during a performance of Handel’s Messiah, which the society sang at its first concert in 1857 – a concert attended by at least 1,050 people who had been brought to Darlington’s Central Hall by special excursion trains from east and west.

But where the baton has been these last 100 or so years, no one really knows. It was discovered among the effects of Molly Pearson, who died earlier this year in Middleton-in-Teesdale, but who was born in Gunnerside in 1925 and farmed in Swaledale most of her life.

“We don’t have a clue where it came from,” said Molly’s son, James, who lives in Mickleton and who, with his siblings, Barbara and Chris, decided to return it to the choral society.

As an inscribed silver plaque on the baton says, it was presented by the choral society to conductor JW Marshall on March 3, 1863.

The society was founded in late 1856 with the 27-year-old organist of Richmond parish church, James Marshall, at the helm. He prepared a 72-strong choir and a 15-strong orchestra to perform Handel’s masterpiece, with soloists to be brought in from as far away as Manchester.

The concert on January 14, 1857, was eagerly anticipated. “Mr Crawford’s organ has now been erected in the Central Hall,” said the Darlington & Stockton Times a week before, with little concern for double entendres, “and that gentleman has spent considerable time and labour upon tuning and preparing it.” He’d brought it all the way from Bishop Auckland.

The Stockton & Darlington Railway laid on return trains from Middlesbrough, Stockton, Yarm, Bishop Auckland and Barnard Castle.

“The room will be made comfortably warm,” promised an advert, and 900 tickets were sold in advance.

“Early in the afternoon, vehicles began to come in from the country districts, carrying hale farmers and their wives and daughters,” said the D&S Times. “Gigs and traps were drawn up to the causeway side in long prim rows ... and at six o’clock, all the staircases were blocked and the approaches thronged with an anxious crowd.

“By seven o’clock, the Central Hall presented one of the most brilliant spectacles witnessed in Darlington for many years. Every recess and corner into which a seat could be thrust had been made available, and the mass of faces seemed to be as closely packed as in those terrible crushes known by the name of “fancy fairs”.

Mr Marshall picked up his baton, and began.

“Never were three hours and a half of more perfect enjoyment afforded to the individuals of the great mass who thronged the Central Hall,” said the paper’s unnamed reviewer, who penned several thousand words of in-depth criticism. “Seldom has the oratorio been rendered with an accuracy more critically correct, or a feeling more chaste and appreciative.”

It all went swimmingly – until the most famous part was reached. The critic wrote: “It was in the Hallelujah chorus that the only perceptible hitch of the entire performance was made, and this was one much to be regretted.”

The drums, said the reviewer, had been “very judiciously managed” by Mr Airey, but as the chorus approached, the experienced ear of the band leader and first violinist, Mr Woodhams, of Richmond, “detected an erratic movement which certainly escaped amateurs and inexperienced persons”.

Mr Woodhams got up from his seat, went over to the timpani, relieved Mr Airey of the sticks, “and took the drums under his own management.

“Unfortunately, in the confusion, he drummed once too often instead of keeping the rest, as marked in his score.

“No one, we are sure, more regretted the disagreeable faux pas than Mr Woodhams himself.”

Overall, though, the Messiah was a triumph. “A more brilliant success the society and its most hearty friends could not have desired,” said the D&S Times. “Nothing before had been known like it in the district. It was a first awakening of musical fervour.”

Nothing has been known like it in the district since. The choral society continued with its well-received works, although nothing quite matched the fervour of the first. In 1863, it presented Mr Marshall with the silver-tipped baton to mark “the indefatigable endeavours he has made to promote the welfare of sacred music in Darlington”.

Perhaps he conducted with it throughout the remaining 30 years of his career before he retired in 1894. He died, aged 64, in 1896, and when his effects were dispersed, somehow his silver-tipped baton made it to Gunnerside, and it entered the possession of Molly’s Rutter family of farmers.

“She was in the Gunnerside Methodist Chapel Choir,” says her son, James. “Perhaps there’s a connection there?”

Now, the baton is back in the hands of the choral society, and tomorrow, current conductor Richard Bloodworth will guide the singers through Messiah with it – but with its silver tips and plates, it is rather heavy, so he may not make it through to the end, even if he doesn’t spin it out to 3½ hours, as Mr Marshall managed.

Darlington Choral Society and the Mowbray Orchestra, conducted by Richard Bloodworth, perform Handel’s Messiah on Saturday, November 28, at 7.15pm in Central Hall, the Dolphin Centre, Darlington. Tickets are £12 (£5 students) and are available from the Dolphin Centre box office or on the door.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here