“OH, my dear Jane, you cannot tell my feelings when I go to bed,” wrote the convicted hook-handed police killer Robert Kitching from the condemned cell in York castle. “I think about you, and I keep thinking there are not many more nights for me to go to bed alive, and when I wake, my dear wife, it is soon in my head about me being condemned to death.

“My dear Jane, I don’t want to say anything about it, but it will be a sad morning when it comes.”

We told last week of the murder of Sgt James Weedy, of Bedale police, at Leeming village on September 19, 1890 – “one of the most shocking crimes ever perpetrated in North Yorkshire”, said the D&S Times at the time.

Suspicion had fallen, without any room for doubt, on Kitching, a seedsman and market gardener, who was a wrong ’un. He had been declared bankrupt in Boroughbridge five years earlier and had returned to his native Leeming village where a gun had exploded, removing his left hand. This caused him to wear a hook in his sleeve – an implement with which he is said, in drink, to have gouged men’s eyes out.

Sgt Weedy, 43, was a father of 12 who lived next door to the Black Ox Hotel in Leeming village – less than 80 yards from Kitching’s cottage. Weedy was an exemplary policeman - “one of the smartest and most useful members of the North Yorkshire force”, according to his Chief Constable - and so had plenty of previous with Kitching, 31.

On the night in question, Kitching had been drinking for hours in the Leeming Bar Hotel (now the Corner House hotel), leaving his horse and cart outside, and unlit, on the busy Great North Road. As dark fell, the sergeant had asked Kitching outside to remove it. Kitching had reluctantly complied, swearing oaths and chuntering his usual threats.

But this time, after closing time, he had crossed Leeming Beck and returned home, filled his gun, and shot Weedy outside his garden gate.

The trial was held at the Yorkshire Assizes was held on December 9. “On entering the dock, the prisoner took a survey of the court, which was crowded,” reported the D&S. “He looked ill, and somewhat careworn, but when asked to plead, he replied in a firm voice: “Not guilty”.”

At first Kitching claimed the shooting was an accident. Then he claimed that Weedy had struck the first blow with a stick. But when his father-in-law, Edmund Caygill, with whom he had spent the chaotic hours between the shooting and his arrest on his stall in Richmond market, was unable to corroborate either story, the jury at the Yorkshire Assizes quickly found him guilty – although they added a “recommendation for mercy”.

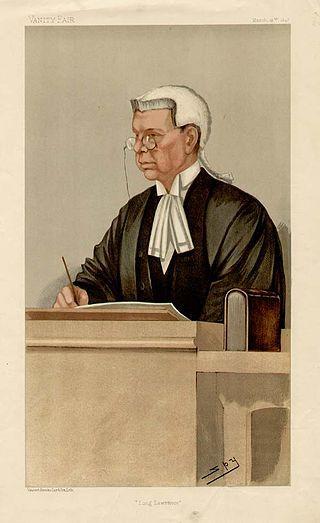

Justice Mr Lawrance – known as “Long” Lawrance due to the unusual length of his deliberations – donned the black cap and was surprisingly abrupt. “I will forward to the proper quarter the recommendation to mercy, but I can hold out no hope that that will lead to any commutation of your sentence,” he told him.

The D&S reported: “His lordship, having earnestly advised the prisoner to avail himself of the ministrations of those with whom he would be brought into contact, passed sentence of death in the usual form.”

They didn’t mess around in the 1890s. Kitching was scheduled to die less than three-and-a-half months after he had killed the policeman. As the judge had suggested, the Home Secretary dismissed all pleas for clemency, despite Kitching’s handwritten claims that the shooting was an accident.

The condemned man bitterly blamed his father-in-law for not fabricating an alibi for him.

In a letter sent from his cell to his wife, and published in the D&S, Kitching wrote: “I don’t know what your father has against me. He could have been the means of saving my life and you from being a widow, and my dear little children from being fatherless.

“What does he think to himself now he has got me put to death, and his own daughter left a widow, and four poor little children fatherless.

“But my dear and loving wife, if I could only get back to you I would lead a different life to what I have done. This is a dark Christmas for us.”

The New Year was no better. January 2 was the day of execution.

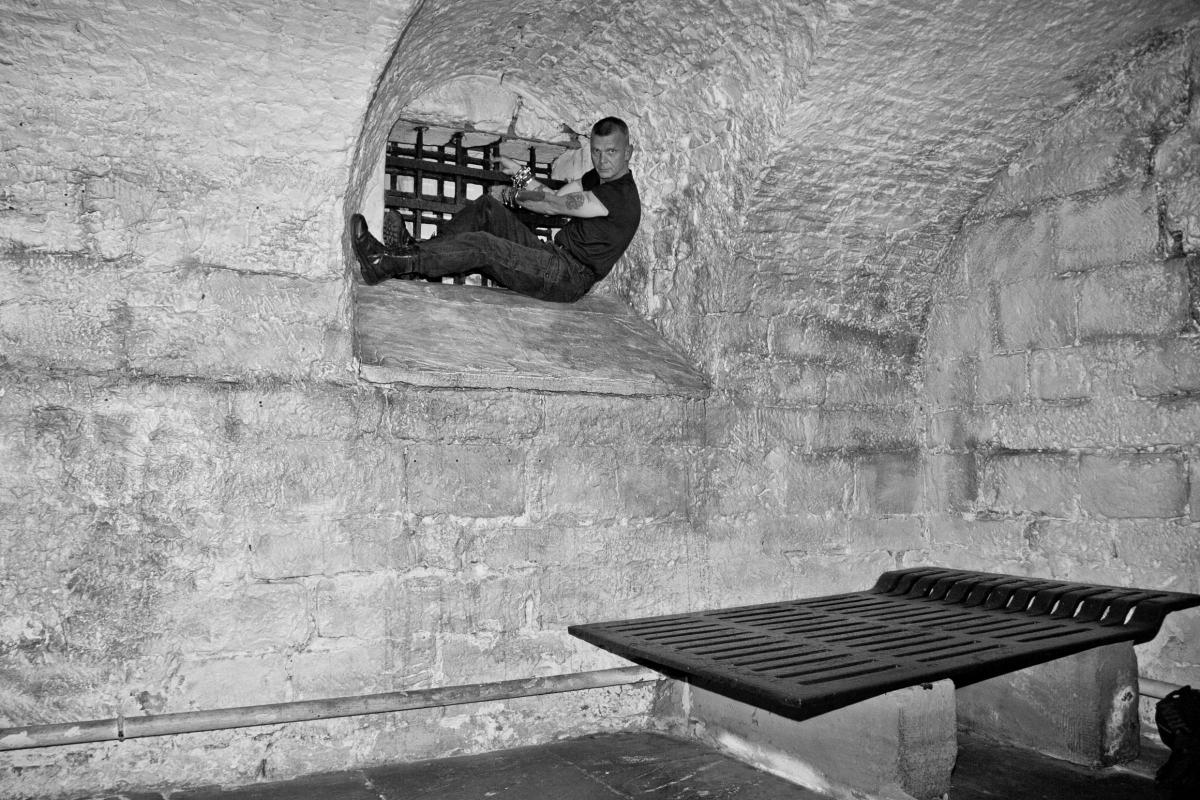

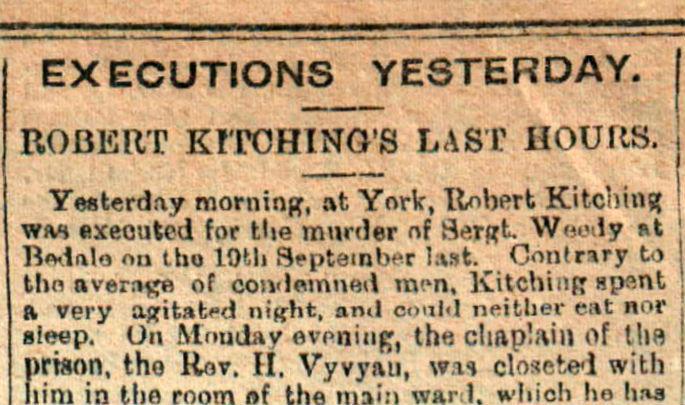

“The condemned cell (at York castle) is a very gruesome place, and one of the windows commands a view of the scaffold, which is immediately adjacent,” began the D&S in its report of the grim proceedings.

It said he had passed his last night sleeplessly, lying restlessly on his bed for two hours before rising at 6.30am when breakfast was taken to him.

“He was however unable to partake of any food, but drank some tea, and at intervals refreshed himself with that beverage up to the time of his removal to the scaffold,” said the D&S.

Praying continually with the prison chaplain, Kitching does appear to have found some composure in his final moments. He attended a service at 7am, concealed from the other inmates by a screen, and then was ready to make a confession.

“Kitching made a communication to the prison chaplain in which he said that he took the gun, loaded it, and went out of the house with the full intention of shooting Weedy, though, at the same time, he said he had the half hope that he would not meet him,” said the D&S. “He covered Weedy with the gun as he came up to the gate and pulled the trigger, but it missed fire. Afterwards, as Weedy closed with him, he fired directly at him.”

At 7.57am – with just three minutes of life remaining, executioner James Billington, of Preston (a former Sunday school teacher who had become obsessed with the science of the drop), entered the cell and found Kitching praying on his knees.

“The governor touched the culprit on the shoulder and he at once rose to his feet and submitted passively to the process of pinioning, though he trembled violently,” said the D&S.

“The culprit walked firmly to the scaffold where he took his stand with a warder on either side to support him in the event of his nerve giving way. This precaution was, however, unnecessary, the unhappy man standing unassisted while his legs were pinioned and the operations of drawing the cap over his face and adjusting the noose were performed.

“Just as the lever was being drawn by the executioner, Kitching reeled, but the trap fell, the rope immediately tightened, and the culprit met his doom. Billington allowed a drop of 7ft 6ins, Kitching being a man of slight build, and weighing only about nine stone.

“Death appeared to be instantaneous and as far as could be seen not a muscle quivered after the drop.”

The D&S’ reporter did not personally witness this execution although he reported it in cold, detached detail, in curious contrast to 1865, when the paper’s reporter personally witnessed the last public execution at Old Elvet in Durham and had been thoroughly appalled and sickened by the grisly proceedings.

Kitching’s body remained on the gallows for the statutory hour, and was then buried nearby in an unmarked grave.

The D&S concluded its coverage by printing in full his last letter to his wife, Jane, who visited him regularly.

He said: “I should like to have your company as long as I have to live. I often wonder what will become of you and my dear little darlings with you. It breaks my heart to think that I have to be parted from you. I think more about being parted from you than I do about being put to death.

“O what will become of you and my little ones?

“Oh Jane, it is more than I can bear, but it has to be.”

Despite his callous crime and despite his attempts to blame his father-in-law, Kitching’s letter is quite heart-breaking to read.

But there is an abrupt change of tone for the market gardener’s last sentences.

“If you can, you might bring about three plants of carnations, good, strong, large of different colours. I think those will be as good as any that are nearest the trod. These are for the master of the prison. He is very kind to me. Don’t forget, my darling.”

From the D&S Times of…

May 11, 1968

FOR the first time in living memory, a “patch of dry-stony soil” had caved in on the “bleak, windswept moorland between Upper Wensleydale and Swaledale” to reveal another “buttertub”.

The D&S of 50 years ago said: “These deep shafts in the limestone are formed by acid water from the peat seeping down through cracks in the limestone which, over the centuries, eats away the stone into huge vertical holes, which resemble the tubs used years ago for making butter.”

The National Park warden had hastily erected a fence around the new tub, which was only a yard wide at its mouth but was reckoned to be at least 40ft deep, to prevent tourists and sheep from falling down it.

“At this particular point, the peat and turf have been worn away by countless visitors passing the spot to get a close look at a large tub a few yards away, and no one knows why the top should have caved in at this particular time,” said the reporter, who was particularly fond of one word.

“The local guide books extol the Pass with its breathtaking views and urge tourists to visit these natural wonders and the question now arises whether the surrounding moorland is safe, or whether in fact it is riddled with unknown caverns.”

May 11, 1918

IN Richmond, the D&S Times reported, the Wesleyan, National and Roman Catholic schools were all shut due to an outbreak of measles.

May 8, 1868

NEXT Tuesday, the D&S said, would be “a red letter day at Middleton-in-Teesdale on the occasion of the official opening of the Tees Valley Railway”.

It said: “The event has now been looked forward to for some time by the inhabitants, who have decided to make it a general holiday and a day of public rejoicing; everywhere we hear of something being done to further the object they have in view.”

The D&S said: “We wish them all every success, and may old Sol shine forth its brightest rays on the occasion.”

We should probably mark the 150th anniversary of the opening of this line next week…

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here