CAN dry and dusty old stones ever be interesting? The opening of Open Treasure, the £10.9m exhibition in Durham Cathedral, shows that they can.

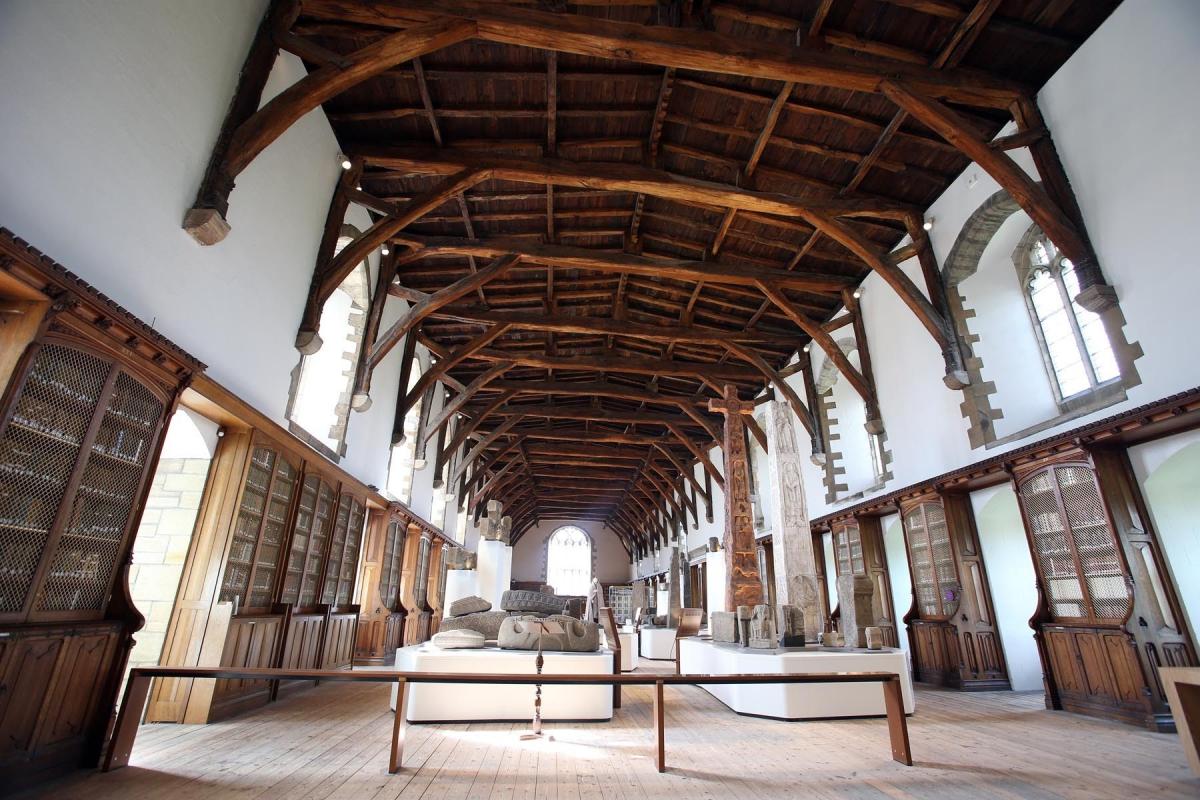

The exhibition is held in a couple of stunning spaces – the 14th Century Monks’ Dormitory, with the largest oak-beamed ceiling outside of Westminster Hall, and the Great Kitchen, with its truly majestic octagonal roof – and it begins with an artful arrangement of carved stones from the Viking era more than 1,000 years ago.

Many of the stars of the show are local stones, from Hurworth, Neasham, Gainford, Ingleby Arncliffe and especially Brompton, near Northallerton.

In 1867, St Thomas’ Church, overlooking the village green, was thoroughly restored. Perhaps too thoroughly, as many of its interesting antiquities were restored away, but in the foundations of the chancel were found ten hogback stones – one of the finest collections of these beautiful and curious stones in the country.

Five of the stones remain in Brompton, but the best five were spirited away to Durham Cathedral, and now greet visitors as they arrive in Open Treasure.

Hogbacks get their name because usually at either end they have carvings of hogs’ heads. The heads face each other and they appear to be chewing on a plait which stretches between them along the top of the stone. Intricate carved patterns then tumble down the sides.

These stones seem to have been houses for the dead and they were probably gravemarkers. The shape appears to have been a pagan Scandinavian tradition which the Vikings brought to North Yorkshire where it met the local Christian tradition of stone carving. In fact the hogs may be a symbol of a pagan god, Frey.

However, Brompton’s hogbacks, from the early 10th Century, are highly unusual because they don’t have hogs’ heads – they have muzzled bears’ heads.

No one knows why.

The other fine local collection of hogbacks is at Sockburn, seven miles from Brompton, and there are such similarities between the works that some of them may have been done by the same hand. There is speculation that Brompton and Sockburn may have worked together as a school, or even factory, knocking out carvings for other, less talented villages.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here