To mark the start of an exhibition about trainspotting at the National Railway Museum in York, Bob Gwynne, associate curator of rail vehicles, charts its surprisingly fascinating history

INTEREST in railways goes back a long way – as long ago as 1807 visitors to Newcastle were being advised on how to take a trip on “Kitty’s Drift”, the world’s first underground railway.

When the first train ran on the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825, it had more than 600 of the first rail enthusiasts hitching a ride, and the Durham County Advertiser said: “The whole population of the towns and villages within a few miles of the railway seem to have turned out, and we believe we speak within the limits of truth, when we say that not less than 40 or 50,000 persons were assembled to witness the proceedings of the day.”

By 1830, just before the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester railway, the actress Fanny Kemble (then aged 21) charmed George Stephenson sufficiently to ride with him on the locomotive up Olive Mount cutting.

The engine was a “magical machine, with its flying white breath and rhythmical unvarying pace”, and this is the first recorded incident of a member of the public getting a footplate ride.

In 1836, a Mr E Dixon published a “full detailed list” of the Liverpool and Manchester railway locomotives including those “sold”, “broken up” or “done with”, although as yet there is no evidence of anyone taking locomotive numbers.

That first evidence comes from an article published in the Great Western Railway magazine in 1935 entitled “A Fascinating Souvenir of Broad Gauge Days”. It was about a pocket book from 1861 which recorded names and numbers of locomotives passing Westbourne Park, London. The spotter? One Fanny Johnson, then aged 14 – and she had “cleared” her Gooch 8 footers.

By the end of the 19th Century, there were magazines and books galore to cater for the interest and railways. In 1899, Holland and Company, “railway booksellers” based in Birmingham, published a range of titles relating to the London and North Western Railway including The Register of all L&NWR Locos by S Cotterell and GH Wilkinson. This is book by enthusiasts for enthusiasts, and the authors claimed for it “the distinction of being the first and only book ever devoted entirely to the locomotives of one railway company”.

They also noted that “among the young people and many admirers of a good engine, the locality and even the sheds frequented by the locomotives are a source of great interest”.

Handily pocket-sized, the end piece of the book put in a request for “Names, Numbers and Dates wanted”.

In 1901, The Railway Times appeared. It was the print equivalent of a modern blog containing locomotive notes and lists and circulated to “locoists” in south London.

An early copy has a list of L&NWR Precedent class engines with crosses next to five of them, and it gives details of “locomotive observations”(spotting) at Euston, Paddington and King’s Cross. However, the author has issues with being seen to be a spotter, clearly not a modern complaint. He writes: “To my mind, to take a public interest in engines and railways is right and proper, but to be seen at a station writing down the numbers of engines as they pass is childish. I make my notes in a quiet corner if possible, so that I may be, for all the casual observer knows, jotting down a stray thought, or a business note.”

Cannon Roger Lloyd’s book The Fascination of Railways was published in 1951 and includes a recollection from a woman who in 1912 “during the Christmas holidays…you could have seen me with a little boy of 12 (now my husband) by the entrance to Clayton Tunnel”.

Forty years later, she confessed to Cannon Lloyd that “we still go to stations or points of vantage wherever we are able to indulge in our favourite pastime”.

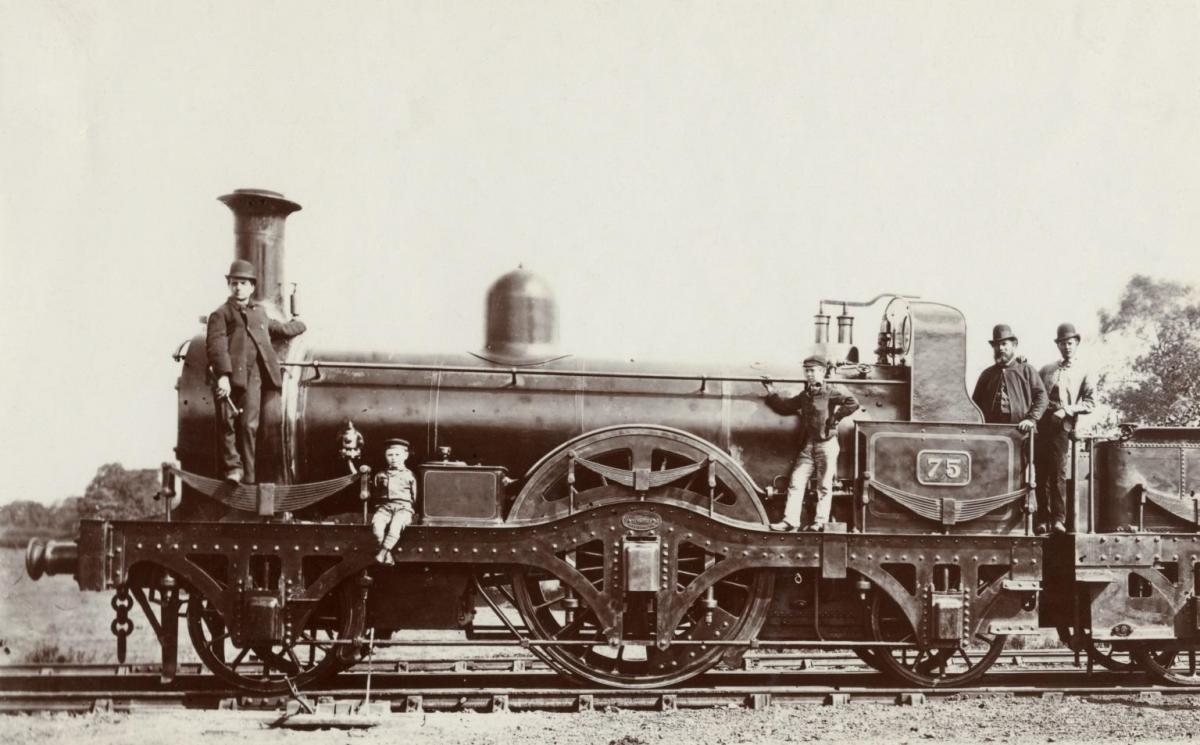

So before the bloody debacle of the First World War there were people in the UK out trainspotting and (if they could afford it) photographing trains, and the grouping of the railways after the war into big companies made “study” of the railways easier.

In 1919, for example, the Great Western Railway first published a book comprising of a list of its engines, which was regularly reprinted. In 1935, the LNER magazine said that the book “continues to be a great friend to harassed fathers whose sons are railway enthusiasts, and which boy is not?”

And it was not only boys. Cannon Lloyd’s book included a story from someone who went trainspotting at New Southgate, in London, in 1938 where he met “four alert looking girls who were obviously watching the rail traffic”. Their notebooks recorded the number, name, type, classification, shed and date seen of every engine.

“When I came to ask them how they came to be so interested as to keep such careful records, they seemed almost at a loss for a reply, as if they were doing the most natural thing in the world. When the train came by, one of the girls said: ‘He was making about 70 I should think’.”

By the time the Second World War came along, railway enthusiasm was evident in many forms, including trainspotting.

In 1942, in the middle of the London blitz, Ian Allan, a 20-year-old clerk in the PR office of the Southern Railway at Waterloo, suggested publishing a simple user-friendly list of all the company’s locomotives to help his office with all the locomotive queries. When his boss refused, Allan went ahead himself with an initial print run of 2,000 copies. This book was the first “ABC” and it swiftly sold out at 1s a copy and a publishing empire was born.

The Southern Railway guide was soon followed by an ABC of Great Western Locomotives, ABC of London Midland and Scottish Locomotives and ABC of LNER locomotives. With business booming, Allan was able to resign from the Southern Railway in 1945, and lubricated by his books, the hobby of trainspotting also boomed. Some in authority found this alarming, even going so far as to ban the practice in several locations including Willesden Junction in 1954.

After boys were arrested for trespass at Tamworth station in 1944 (they had been putting pennies on the line to get squashed while they were trainspotting), Allan came up with the Locospotters Club, which soon had nearly 300,000 members.

The ABCs were produced through to 1989, surviving the end of steam and of most of the diesels that replaced them.

By then, British Railways was using its Total Operations Processing System which managed the whereabouts of all of its locos on a computer.

Anyone with a friend in the control room, and many people knew someone, would get a tip-off of where a certain engine was going to be at a certain time, and so the need to stand by the trackside and actually wait to see what turned up was slipping into the computer age.

Today, almost anything railway can be followed from home with chat rooms like National Preservation enabling the sharing of information, right though to the current “hot” website for those interested in train movements, Real Time Trains.

So today it is possible that somewhere out there is the equivalent of Ms Johnson, only she is armed with a smartphone, watching trains with the innocent fascination that still baffles so many people, including most of the media.

Comments: Our rules

We want our comments to be a lively and valuable part of our community - a place where readers can debate and engage with the most important local issues. The ability to comment on our stories is a privilege, not a right, however, and that privilege may be withdrawn if it is abused or misused.

Please report any comments that break our rules.

Read the rules here